Chapter 9

Building a Simple LLM from Scratch Using Rust

"Building machine learning models from scratch offers invaluable insights into the fundamental workings of AI, and Rust’s focus on safety and performance makes it a powerful tool for developing reliable, efficient systems." — Andrew Ng

Chapter 9 of LMVR provides a comprehensive guide to building a simple language model (LLM) from scratch using Rust. It begins with an introduction to language models, highlighting the evolution from traditional statistical methods to modern deep learning approaches. The chapter then covers the setup of a Rust environment, emphasizing the language's safety and performance features, followed by detailed sections on data preprocessing, tokenization, and model architecture. It walks through the training process, including optimization techniques and hyperparameter tuning, and explores the importance of evaluation and fine-tuning for specific tasks. Finally, it discusses the deployment of LLMs, addressing challenges such as scalability and latency, and concludes with a look at the future directions and challenges in building LLMs with Rust.

9.1. Introduction to Language Model

Language models are probabilistic frameworks designed to assign probabilities to sequences of words in a language. They play a fundamental role in natural language processing (NLP) tasks such as machine translation, speech recognition, and text generation. By modeling the likelihood of word sequences, language models enable machines to understand and generate human language effectively.

The primary objective of a language model is to compute the joint probability of a sequence of words $w_1, w_2, \dots, w_n$. This can be expressed using the chain rule of probability:

$$ P(w_1, w_2, \dots, w_n) = \prod_{t=1}^{n} P(w_t | w_1, w_2, \dots, w_{t-1}). $$

This formulation decomposes the joint probability into a product of conditional probabilities, where each term represents the probability of a word given all the preceding words in the sequence.

The Markov property is a foundational concept in stochastic processes, stating that the future state of a process depends only on the present state and is independent of past states. Mathematically, for a stochastic process $\{X_t\}$, the Markov property is expressed as:

$$ P(X_{t+1} | X_t, X_{t-1}, \dots, X_1) = P(X_{t+1} | X_t). $$

In the context of language modeling, directly applying the Markov property would imply that the probability of the next word depends only on the current word, ignoring all earlier words. However, natural language exhibits dependencies that often span multiple words. To capture more context, higher-order Markov assumptions are made, where the probability of the next word depends on a fixed number of previous words, not just the immediate one.

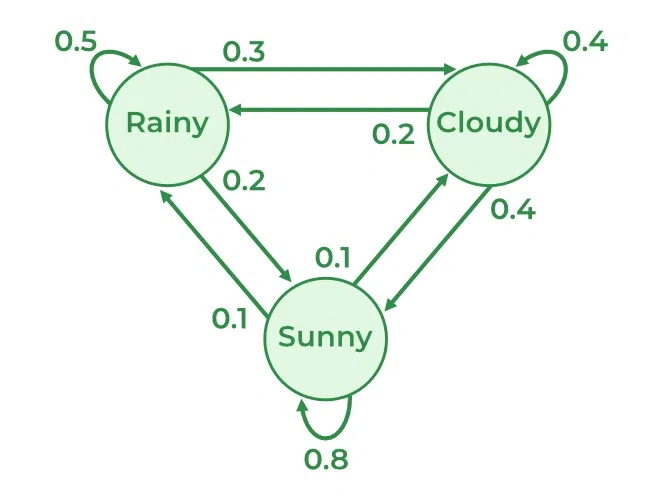

In natural language processing (NLP), the Markov property is the idea that the likelihood of a future word depends only on the current word, not on any words that came before it. Imagine you're predicting the weather based on simple patterns: "Cloudy," "Rainy," and "Sunny." If the forecast only depends on today's weather, we say it has the Markov property. For instance, if it's "Cloudy" today, the chance of tomorrow being "Rainy" might be high, while the chance of "Sunny" is lower. In a 1st-order Markov model, tomorrow’s weather would only depend on today, so if it's "Cloudy," we wouldn’t consider the day before yesterday's weather, even if it was also "Cloudy." This simplification makes predictions easier because it reduces the context needed to only the most recent "state"—in this case, today’s weather. Similarly, in NLP, a Markov model would predict the next word in a sentence based only on the word immediately before it, ignoring further past context.

Figure 1: Simple illustration of Markov model in Weather prediction (Credit: GeeksforGeeks).

An $(n-1)$-order Markov assumption leads to an nnn-gram model, approximating the conditional probability as:

$$ P(w_t | w_1, w_2, \dots, w_{t-1}) \approx P(w_t | w_{t-(n-1)}, \dots, w_{t-1}). $$

This approximation reduces computational complexity by limiting the history to the previous $n-1$ words. For example, in a bigram model (where $n = 2$), the probability of a word depends only on the immediately preceding word:

$$ P(w_t | w_1, w_2, \dots, w_{t-1}) \approx P(w_t | w_{t-1}), $$

and the sequence probability becomes:

$$ P(w_1, w_2, \dots, w_n) \approx \prod_{t=1}^{n} P(w_t | w_{t-1}). $$

In a trigram model (where $n = 3$), the probability depends on the two preceding words:

$$ P(w_t | w_1, w_2, \dots, w_{t-1}) \approx P(w_t | w_{t-2}, w_{t-1}), $$

resulting in:

$$ P(w_1, w_2, \dots, w_n) \approx \prod_{t=1}^{n} P(w_t | w_{t-2}, w_{t-1}). $$

The conditional probabilities in n-gram models are typically estimated from a large corpus using Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE). The estimation formula is:

$$ P(w_t | w_{t-(n-1)}, \dots, w_{t-1}) = \frac{\text{Count}(w_{t-(n-1)}, \dots, w_{t-1}, w_t)}{\text{Count}(w_{t-(n-1)}, \dots, w_{t-1})}, $$

where $\text{Count}(w_{t-(n-1)}, \dots, w_t)$ is the number of times the sequence occurs in the corpus. However, this approach faces challenges such as data sparsity, as many possible n-grams may not appear in the training data, and high dimensionality, since the number of parameters grows exponentially with nnn and the vocabulary size.

To address data sparsity, smoothing techniques adjust the estimated probabilities to assign some probability mass to unseen n-grams. Common smoothing methods include Add-One (Laplace) smoothing, Good-Turing discounting, and Kneser-Ney smoothing. For example, Add-One smoothing modifies the MLE formula to:

$$ P_{\text{Laplace}}(w_t | w_{t-(n-1)}, \dots, w_{t-1}) = \frac{\text{Count}(w_{t-(n-1)}, \dots, w_t) + 1}{\text{Count}(w_{t-(n-1)}, \dots, w_{t-1}) + V}, $$

where $V$ is the size of the vocabulary.

Despite these techniques, $n$-gram models have significant limitations. They cannot capture dependencies beyond $n-1$ words, ignoring long-range syntactic and semantic dependencies. Moreover, high-order n-gram models require large amounts of data to estimate probabilities reliably, and storing all possible $n$-gram counts becomes impractical for large nnn and vocabularies. These limitations have motivated the development of more sophisticated language models that can capture longer dependencies.

Neural Network Language Models (NNLMs) have emerged to overcome the limitations of n-gram models. NNLMs use neural networks to model the conditional probabilities and can capture long-range dependencies by using continuous representations of words (embeddings) and architectures capable of processing sequences. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), for instance, maintain a hidden state that captures information from all previous time steps. The mathematical formulation involves updating the hidden state $\mathbf{h}_t$ using:

$$ \mathbf{h}_t = f(\mathbf{W}_h \mathbf{h}_{t-1} + \mathbf{W}_x \mathbf{x}_t + \mathbf{b}_h), $$

where $\mathbf{x}_t$ is the input embedding for word $w_t$, and producing the output probability distribution using:

$$ P(w_t | w_1, \dots, w_{t-1}) = \text{Softmax}(\mathbf{W}_o \mathbf{h}_t + \mathbf{b}_o). $$

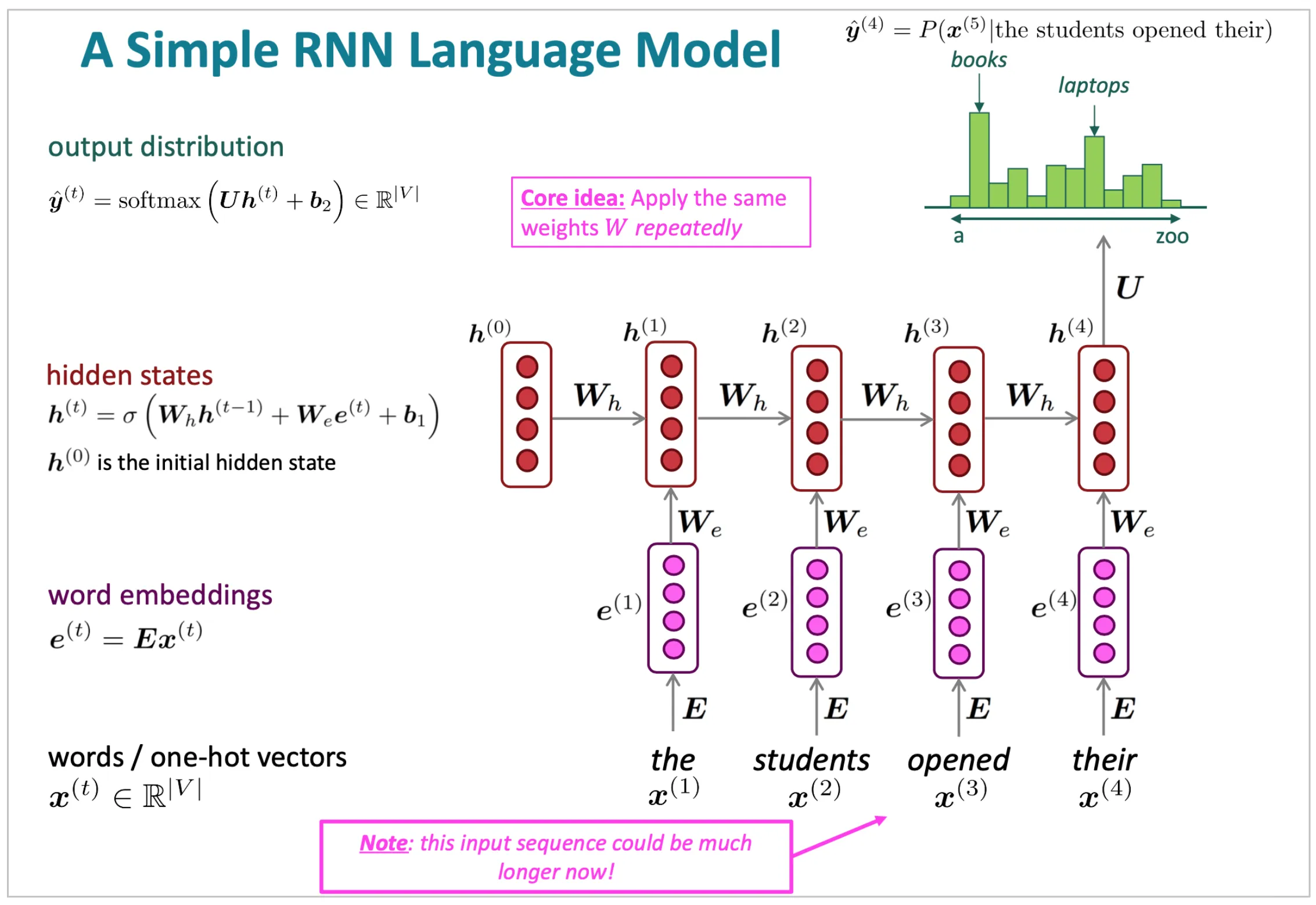

Figure 2: Illustration of simple language model using RNN.

In a simple recurrent neural network (RNN) language model, we process each word in a sequence step-by-step. For each word at position $t$, represented by $x^{(t)}$, we first map it to a word embedding $e^{(t)} = E \cdot x^{(t)}$, where $E$ is an embedding matrix that converts $x^{(t)}$ into a dense vector capturing word meaning. This embedding is passed into the RNN, which maintains a hidden state $h_t$ that captures contextual information from previous words in the sequence. The hidden state $h^{(t)}$ is computed based on the current word embedding $e^{(t)}$ and the previous hidden state $h^{(t-1)}$, using a set of weights $W$ that are applied repeatedly at each step. Finally, the model outputs a distribution $y_t$ over possible next words, predicting probable continuations like "books" or "laptop" after the input sequence "the students opened their...". The key idea of applying the same weights $W$ repeatedly across each timestep is central to RNNs; it allows the model to generalize patterns learned from one part of the sequence to another, providing consistency and enabling the model to handle varying sequence lengths. This repeated application of weights also enables the network to capture sequential dependencies effectively, as each $h^{(t)}$ reflects cumulative context up to that point in the sequence.\ \ Advanced architectures like Long Short-Term Memory networks (LSTMs) and Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs) address issues such as the vanishing gradient problem, allowing for better learning of long-range dependencies. Furthermore, the introduction of the Transformer architecture, which relies on self-attention mechanisms rather than recurrence, has significantly advanced language modeling. The self-attention mechanism allows the model to weigh the influence of different positions in the input sequence, with the attention computed as:

$$ \text{Attention}(Q, K, V) = \text{Softmax}\left( \frac{QK^\top}{\sqrt{d_k}} \right) V, $$

where $Q, K, V$ are query, key, and value matrices derived from the input embeddings, and $d_k$ is the dimensionality of the key vectors.

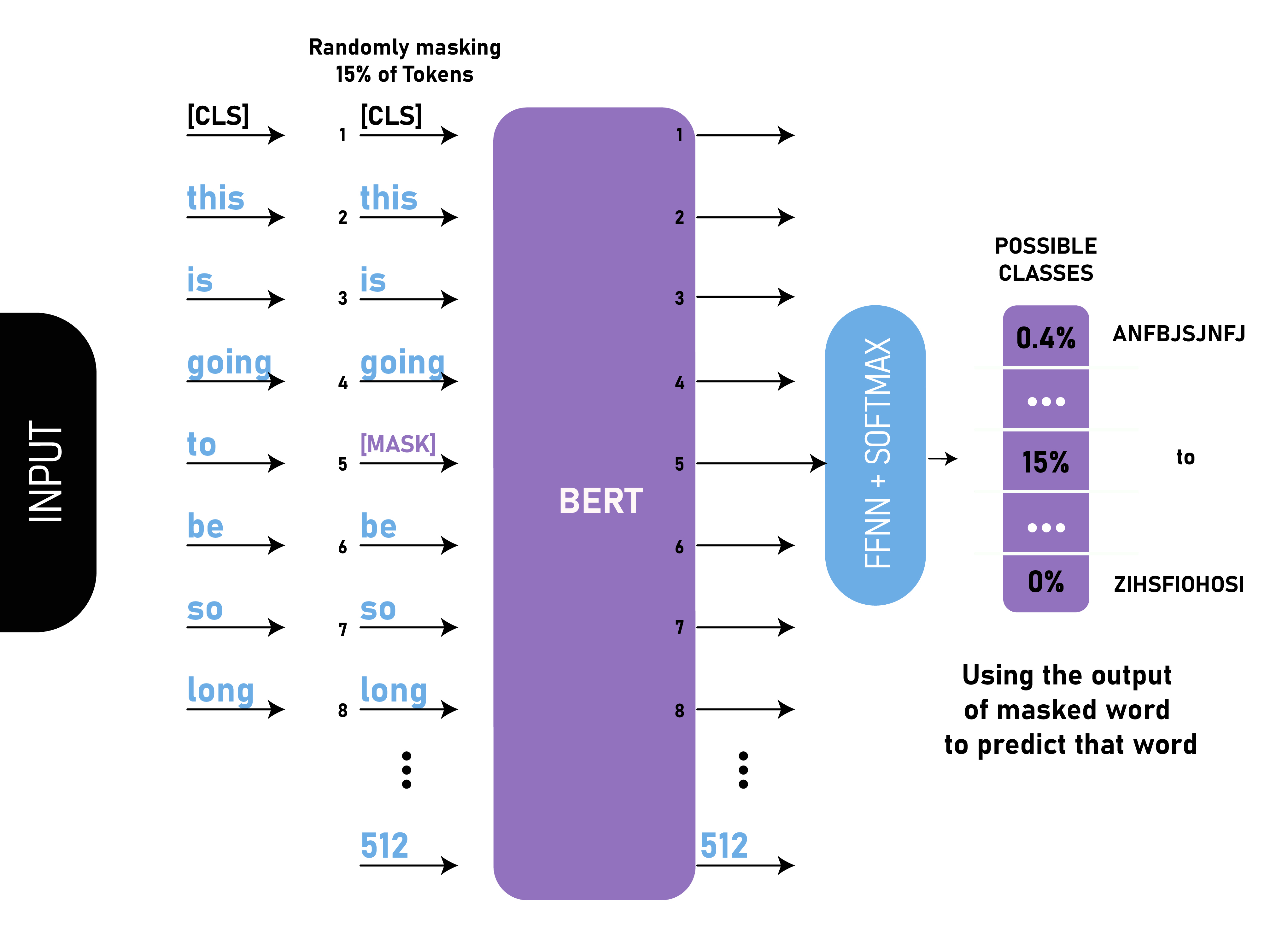

Language model pretraining techniques, such as Masked Language Modeling (MLM) used in BERT and autoregressive modeling used in GPT, have further enhanced the capabilities of language models. These models are trained on large corpora to predict missing words or the next word in a sequence, enabling them to capture complex patterns and dependencies in language.

Figure 3: Illustration of BERT model for language model (Credit: GeeeksforGeeks).

The evaluation of language models often involves metrics like perplexity, which measures how well a language model predicts a sample. Perplexity is defined as:

$$ \text{Perplexity}(P) = \exp\left( -\frac{1}{N} \sum_{t=1}^{N} \log P(w_t | w_1, \dots, w_{t-1}) \right), $$

with lower perplexity indicating better predictive performance. Entropy is another metric that quantifies the uncertainty in predicting the next word, defined as:

$$ H(P) = -\sum_{w} P(w) \log P(w). $$

Understanding the Markov property and Markov assumptions is crucial for simplifying the modeling of complex probability distributions in language. By limiting dependencies to a fixed context window, n-gram models make the computation of sequence probabilities tractable. However, these simplifications come at the cost of ignoring longer-range dependencies inherent in natural language. The development of neural network-based language models addresses these limitations by capturing semantic and syntactic structures over longer contexts, leading to superior performance in various NLP tasks.

These advancements have significant implications for both theoretical understanding and practical applications. They enhance the quality of machine translation, speech recognition, conversational agents, predictive text input, summarization, and question-answering systems. By leveraging continuous representations and architectures capable of capturing long-term dependencies, modern language models are instrumental in the ongoing development of NLP technologies.

In conclusion, the Markov property and higher-order Markov assumptions have been essential in the evolution of language modeling, providing a foundation for the initial approaches to sequence prediction. The limitations of $n$-gram models due to their reliance on these assumptions have spurred the development of advanced models like neural networks and Transformers, which better capture the complexities of human language. The mathematical formulations and concepts discussed are fundamental in understanding and improving language models, contributing to advancements in NLP and enhancing machines' ability to process natural language.

In Rust, we can illustrate a bigram model (1st-order Markov assumption) with code that counts word pairs and calculates transition probabilities based only on the immediately preceding word.

use std::collections::HashMap;

fn main() {

let text = "the quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog";

let bigram_counts = create_bigram_counts(text);

let bigram_probabilities = calculate_bigram_probabilities(&bigram_counts);

for ((w1, w2), prob) in bigram_probabilities.iter() {

println!("P({} | {}) = {:.4}", w2, w1, prob);

}

}

fn create_bigram_counts(text: &str) -> HashMap<(String, String), usize> {

let words: Vec<&str> = text.split_whitespace().collect();

let mut bigram_counts = HashMap::new();

for i in 0..words.len() - 1 {

let bigram = (words[i].to_string(), words[i + 1].to_string());

*bigram_counts.entry(bigram).or_insert(0) += 1;

}

bigram_counts

}

fn calculate_bigram_probabilities(bigram_counts: &HashMap<(String, String), usize>) -> HashMap<(String, String), f64> {

let mut probabilities = HashMap::new();

let mut word_counts = HashMap::new();

for ((w1, _), count) in bigram_counts.iter() {

*word_counts.entry(w1.clone()).or_insert(0) += count;

}

for ((w1, w2), count) in bigram_counts.iter() {

let total_count = *word_counts.get(w1).unwrap();

probabilities.insert((w1.clone(), w2.clone()), *count as f64 / total_count as f64);

}

probabilities

}

In this code, we count bigrams—pairs of consecutive words in a sequence—and use these counts to estimate conditional probabilities, $P(w_{t+1} | w_t)$, which represent the likelihood of a word $w_{t+1}$ following a word $w_t$. This probability is calculated by dividing the count of each bigram (the specific word pair) by the count of the first word in the pair. This approach assumes a 1st-order Markov property, meaning that the probability of a word depends only on the immediately preceding word, simplifying the model to consider only recent context.

While Markov assumptions simplify complex dependencies in language modeling, they are limited in capturing long-range relationships, as they rely on immediate or short-term context. In natural language, dependencies often span multiple words or sentences—patterns that n-gram models struggle to represent fully. Neural models address this limitation by encoding words and their contexts as dense vectors in a high-dimensional space, allowing for richer and more adaptable representations. Using architectures like recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and Transformers, neural models maintain context across entire sentences or paragraphs, significantly outperforming Markov models in capturing nuanced relationships. This shift from Markov-based, discrete probability tables to neural network-based, continuous vector representations marks a foundational evolution in language modeling. Neural networks can predict the next word $P(w_{t+1} | w_1, \dots, w_t) = \text{softmax}(W \cdot h_t + b)$, where $h_t$ is the hidden state, $W$ and $b$ are learned parameters, and softmax ensures a probability distribution. Unlike $n$-gram models, which rely on discrete word counts, neural models use continuous embeddings that capture semantic similarities. By dynamically adjusting to the entire sequence context, these models enable more robust predictions across longer dependencies, forming the basis for today’s sophisticated language models.

While Rust is not as commonly used for building deep learning models, it provides a high-performance foundation for experimentation with neural networks. Libraries like tch-rs (Rust bindings for PyTorch) allow neural network implementation in Rust. This code creates a synthetic text corpus to train a language model based on an LSTM. A simple word embedding layer is initialized to transform words into dense vector representations, followed by an LSTM layer to capture sequential dependencies in the text. The model is then trained on the synthetic corpus, and its performance is evaluated using the perplexity metric—a measure of how well the model predicts the next word in a sequence. This provides insight into the model’s ability to capture language patterns.

// Importing necessary components from tch library

use tch::{nn, nn::OptimizerConfig, Device, Kind, Tensor};

use tch::nn::RNN; // Import the RNN trait to access the `seq` method for LSTM

// Generate a small synthetic corpus for language model training

fn generate_synthetic_corpus() -> Vec<&'static str> {

vec![

"the cat sat on the mat",

"the dog lay on the log",

"a man ate an apple",

"a woman read a book",

"the child ran to the park",

]

}

// Tokenize the corpus and generate a vocabulary, returning tokenized corpus, VarStore, and vocab size

fn tokenize_corpus(corpus: Vec<&str>) -> (Vec<Vec<i64>>, tch::nn::VarStore, i64) {

let mut tokens = vec![];

let mut vocab = std::collections::HashMap::new();

let mut idx = 0;

// Tokenize each sentence and build a vocabulary map

for sentence in corpus {

let mut sentence_tokens = vec![];

for word in sentence.split_whitespace() {

// Assign a new index if the word is not already in the vocabulary

if !vocab.contains_key(word) {

vocab.insert(word, idx);

idx += 1;

}

// Map word to its index

sentence_tokens.push(*vocab.get(word).unwrap());

}

tokens.push(sentence_tokens);

}

// Initialize a VarStore for model parameters

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(Device::Cpu);

(tokens, vs, idx) // Return tokenized corpus, VarStore, and vocabulary size

}

// Define a simple LSTM-based language model

struct LSTMModel {

embedding: nn::Embedding, // Embedding layer to transform word indices into dense vectors

lstm: nn::LSTM, // LSTM layer to capture sequential patterns

linear: nn::Linear, // Linear layer for output transformation

}

impl LSTMModel {

// Model constructor to initialize layers

fn new(vs: &nn::Path, vocab_size: i64, embed_dim: i64, hidden_dim: i64) -> Self {

let embedding = nn::embedding(vs, vocab_size, embed_dim, Default::default());

let lstm = nn::lstm(vs, embed_dim, hidden_dim, Default::default());

let linear = nn::linear(vs, hidden_dim, vocab_size, Default::default());

LSTMModel { embedding, lstm, linear }

}

// Forward pass for the model to process input tensor and predict next word probabilities

fn forward(&self, xs: &Tensor) -> Tensor {

// Apply embedding to transform word indices into dense vectors and add batch dimension

let embeddings = xs.apply(&self.embedding).unsqueeze(1);

// Pass embeddings through LSTM, returning output and ignoring hidden state

let (output, _) = self.lstm.seq(&embeddings);

// Apply linear layer to transform LSTM output to vocab size for prediction

let logits = output.apply(&self.linear);

logits.squeeze_dim(1) // Remove batch dimension for output consistency

}

}

// Train the model on the tokenized corpus, adjusting weights with Adam optimizer

fn train_model(

model: &LSTMModel,

tokens: Vec<Vec<i64>>,

vs: &nn::VarStore,

epochs: i64,

learning_rate: f64,

) {

// Initialize Adam optimizer with specified learning rate

let mut opt = nn::Adam::default().build(vs, learning_rate).unwrap();

for epoch in 0..epochs {

let mut total_loss = 0.0;

// Loop through each sequence in the corpus

for token_seq in &tokens {

// Prepare inputs (xs) and targets (ys) by shifting tokens

let xs = Tensor::of_slice(&token_seq[..token_seq.len() - 1]).to_kind(Kind::Int64);

let ys = Tensor::of_slice(&token_seq[1..]).to_kind(Kind::Int64);

// Forward pass: predict next word probabilities

let logits = model.forward(&xs);

// Calculate cross-entropy loss, adjusting dimensions as needed

let loss = logits.view([-1, logits.size()[1]])

.cross_entropy_for_logits(&ys);

total_loss += loss.double_value(&[]); // Accumulate loss as f64 for tracking

opt.backward_step(&loss); // Update model parameters

}

// Print average loss for each epoch

println!("Epoch: {}, Loss: {:.4}", epoch + 1, total_loss / tokens.len() as f64);

}

}

// Calculate perplexity, a metric indicating how well the model predicts the test sequences

fn calculate_perplexity(model: &LSTMModel, tokens: Vec<Vec<i64>>) -> f64 {

let mut total_loss = 0.0;

// Loop through each sequence in the corpus

for token_seq in &tokens {

let xs = Tensor::of_slice(&token_seq[..token_seq.len() - 1]).to_kind(Kind::Int64);

let ys = Tensor::of_slice(&token_seq[1..]).to_kind(Kind::Int64);

// Forward pass: predict next word probabilities

let logits = model.forward(&xs);

// Calculate cross-entropy loss, adjusting dimensions as needed

let loss = logits.view([-1, logits.size()[1]])

.cross_entropy_for_logits(&ys);

total_loss += loss.double_value(&[]); // Accumulate total loss as f64

}

(total_loss / tokens.len() as f64).exp() // Calculate and return perplexity

}

fn main() {

// Generate synthetic text corpus and tokenize it

let corpus = generate_synthetic_corpus();

let (tokens, vs, vocab_size) = tokenize_corpus(corpus);

// Initialize the model with vocabulary size, embedding dimension, and hidden dimension

let model = LSTMModel::new(&vs.root(), vocab_size as i64, 50, 100);

// Train the model on the tokenized corpus for 10 epochs with a learning rate of 0.001

train_model(&model, tokens.clone(), &vs, 10, 0.001);

// Evaluate model performance using perplexity metric

let perplexity = calculate_perplexity(&model, tokens);

println!("Perplexity: {:.4}", perplexity);

}

In this code, we start by generating a synthetic corpus of sentences and tokenizing them. The model is implemented with an embedding layer and an LSTM layer using tch-rs. The embedding layer converts words into dense vectors, and the LSTM processes these embeddings to predict the next word in a sequence. During training, we use cross-entropy loss to adjust model parameters. Finally, we evaluate the model by calculating perplexity, derived from the average cross-entropy loss across the test set, to measure the model’s predictive power.

The limitations of traditional models, such as bigrams, are evident in their poor handling of context. Neural models address this by providing continuous representations, leading to their widespread use in industries such as search engines, virtual assistants, and content moderation, where language understanding is critical.

Today’s large language models, such as GPT and LLaMA, extend the neural model framework with billions of parameters and attention mechanisms, enabling unprecedented levels of contextual accuracy. These models are built using massive datasets and advanced pre-training and fine-tuning techniques, driving trends toward improved model efficiency, fine-grained context handling, and real-time adaptability for applications like customer service automation and dynamic content generation.

The mathematical principles and Rust-based examples in this section demonstrate the evolution from simple statistical methods to neural architectures, providing a foundation for building advanced language models in Rust. This progression establishes the groundwork for further exploration of modern LLM architectures in subsequent sections.

9.2. Setting Up the Rust Environment

Here we delve into the technicalities of setting up a Rust environment for developing language models, with an emphasis on tch-rs, a powerful library that binds PyTorch functionality to Rust. Using tch-rs enables direct manipulation of tensors, computation on GPUs, and high-performance matrix operations, all within Rust’s safe memory management model. This combination of efficiency and safety makes Rust particularly appealing for machine learning applications, where memory leaks and concurrency issues can hinder performance.

Rust’s system-level control over memory and its focus on safety make it a strong candidate for machine learning. Unlike languages with garbage collection, Rust’s memory management is deterministic and safe, enforced through its ownership model. By guaranteeing that objects are freed as soon as they go out of scope, Rust eliminates memory overhead and the risk of memory leaks. This deterministic model is particularly valuable in machine learning, where models often involve large tensors and intricate data structures that are memory-intensive.

Rust’s concurrency model, another essential feature for machine learning, provides safe, concurrent programming through zero-cost abstractions and thread safety. This enables parallel computations critical for training large-scale models. For instance, in distributed data processing, the ownership and borrowing mechanisms prevent data races while allowing developers to utilize multi-core processors effectively.

To start building machine learning applications in Rust, you’ll first need to install the tch-rs library, which provides comprehensive bindings to PyTorch. tch-rs enables tensor operations, model serialization, and GPU acceleration, and it exposes most of PyTorch’s deep learning functionality, making it a powerful toolkit for neural network operations in Rust.

To install tch-rs, include it in your Cargo.toml:

[dependencies]

tch = { version = "0.12.0", features = ["cuda"] } // Include "cuda" for GPU support

Once installed, you can begin working with tensors and simple operations. Here’s a basic example of creating and manipulating tensors with tch-rs:

use tch::{Tensor, Device};

fn main() {

// Create a tensor on the CPU

let tensor_a = Tensor::of_slice(&[1.0, 2.0, 3.0]).to(Device::Cpu);

let tensor_b = Tensor::of_slice(&[4.0, 5.0, 6.0]).to(Device::Cpu);

let result = tensor_a + tensor_b;

println!("Result of tensor addition: {:?}", result);

}

In this example, we create two tensors and perform an element-wise addition. This serves as a foundational building block, as tensors are the primary data structure used in neural networks.

To build neural networks, we need to implement matrix multiplications, nonlinear activations, and loss functions. Let’s explore how tch-rs can handle these operations.

A linear (fully connected) layer performs a matrix multiplication and an addition of bias terms. Mathematically, for an input $x$, weight matrix $W$, and bias $b$, the output $y$ of the linear layer is computed as:

$$y = W \cdot x + b$$

In Rust with tch-rs, we define a linear layer and apply it to a batch of inputs as follows:

use tch::{nn, nn::Module, Tensor, Kind, Device};

fn main() {

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(Device::Cpu);

let linear = nn::linear(&vs.root(), 3, 2, Default::default());

// Create a dummy input tensor

let x = Tensor::of_slice(&[1.0, 2.0, 3.0]).to_kind(Kind::Float).view([1, 3]);

let y = linear.forward(&x);

println!("Output from linear layer: {:?}", y);

}

Here, we use nn::linear, which initializes a linear layer with random weights and biases. We feed a tensor x through the layer, and it outputs a transformed tensor, demonstrating the basic feed-forward operation used in neural networks. This operation is fundamental in deep learning, as fully connected layers form the backbone of many architectures.

Let’s construct a simple MLP with one hidden layer to illustrate the use of linear layers, activation functions, and loss computation. The forward pass for a neural network can be expressed as:

$$y = \sigma(W_2 \cdot (\sigma(W_1 \cdot x + b_1)) + b_2)$$

where $W_1$ and $W_2$ are weight matrices, $b_1$ and $b_2$ are biases, and σ\\sigmaσ is a nonlinear activation function, such as ReLU. The loss is computed by comparing the network’s output with the target labels.

use tch::{nn, nn::ModuleT, nn::OptimizerConfig, Device, Tensor, Kind};

fn main() {

// Define a device (use "cuda" for GPU if available)

let device = Device::Cpu;

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(device);

// Define the MLP architecture

let net = nn::seq()

.add(nn::linear(&vs.root(), 3, 128, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(&vs.root(), 128, 64, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(&vs.root(), 64, 1, Default::default())); // Output layer

// Optimizer configuration

let mut opt = nn::Adam::default().build(&vs, 1e-3).unwrap();

// Dummy input and target tensors

let x = Tensor::of_slice(&[0.1, 0.2, 0.3]).to_kind(Kind::Float).view([1, 3]);

let target = Tensor::of_slice(&[0.4]).to_kind(Kind::Float).view([1, 1]);

// Training loop

for epoch in 0..1000 {

// Forward pass and compute mean-squared error loss

let output = net.forward_t(&x, true);

let loss = output.mse_loss(&target, tch::Reduction::Mean);

// Backward pass and optimization step

opt.backward_step(&loss);

// Print loss every 100 epochs

if epoch % 100 == 0 {

println!("Epoch: {}, Loss: {:?}", epoch, loss.double_value(&[]));

}

}

}

This example demonstrates a neural network with two hidden layers, defined using nn::linear layers and ReLU as the activation function. The Adam optimizer is used to update weights and biases by minimizing the mean-squared error (MSE) loss between the model's predictions and the target values. During training, the network undergoes multiple epochs, with each epoch adjusting the model parameters to iteratively reduce the error. This architecture is similar to an MLP, capturing a basic but powerful form of neural networks often used in language model training.

In NLP, text preprocessing transforms raw text into structured data. Tokenization and normalization are critical preprocessing steps, especially for language models, which require transforming each word into a numerical representation.

Here’s how to implement a simple tokenizer in Rust, converting text into lowercase tokens and stripping punctuation.

fn tokenize(text: &str) -> Vec<String> {

text.to_lowercase()

.replace(|c: char| !c.is_alphanumeric() && !c.is_whitespace(), "")

.split_whitespace()

.map(|s| s.to_string())

.collect()

}

fn main() {

let text = "The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog!";

let tokens = tokenize(text);

println!("Tokens: {:?}", tokens);

}

This code converts the input text to lowercase, removes punctuation, and splits it into individual words. Each token (word) can then be mapped to an embedding or index for further processing in a language model.

Rust’s potential in machine learning is becoming more apparent as projects explore its application in AI. For example, industries handling real-time data, like autonomous driving or real-time trading, find Rust valuable due to its low-latency processing and safe memory handling. Rust’s strong concurrency model makes it particularly well-suited for distributed training environments, where multiple models or processes need to be managed in parallel.

The latest trend involves Rust’s integration into machine learning frameworks like tch-rs, which binds PyTorch’s power with Rust’s system-level control, enabling GPU-accelerated computations. By blending the strengths of high-performance systems programming with the demands of modern machine learning, Rust and tch-rs create an efficient and safe ecosystem for building, training, and deploying language models and neural networks.

This section establishes a foundational understanding of setting up and using Rust’s tools for machine learning, making it a compelling choice for developing high-performance LLMs.

9.3. Data Preprocessing and Tokenization

Here, we focus on the robust preprocessing and tokenization processes essential for converting raw text into structured inputs that a language model can process. Tokenization, which breaks down text into smaller units (tokens), and vocabulary construction play crucial roles in shaping a model’s understanding of language. Advanced tokenization techniques and vocabulary management strategies ensure that models can handle diverse linguistic patterns and minimize issues related to out-of-vocabulary (OOV) terms, which are critical for training effective large language models (LLMs).

Data preprocessing is the first step in building a language model and involves cleaning, normalizing, and segmenting text. Cleaning removes punctuation, numbers, and symbols that do not contribute meaningfully to the model’s learning, while normalization (e.g., lowercasing) unifies text representation. Tokenization then breaks the text into smaller components that the model uses to learn patterns in language. Different tokenization methods vary from word-based approaches, which treat each word as a token, to character-based methods, which treat each character as a token. Between these lies subword tokenization, a popular compromise that captures patterns within words, such as prefixes and suffixes, helping with OOV issues and reducing vocabulary size.

The goal of tokenization is to transform text $x$ into a sequence of tokens $T = \{t_1, t_2, \dots, t_n\}$. A tokenizer function $f$ maps text to tokens as follows: $f(x) = T$. The vocabulary $V$, which includes all unique tokens in the corpus, is a crucial component of the model, as it defines the set of all words or subword units that the model can recognize. Mathematically, constructing the vocabulary involves choosing $V$ to minimize OOV occurrences while balancing memory constraints and processing efficiency. A too-large vocabulary increases model complexity and memory demands, while a too-small vocabulary leads to higher OOV rates, which can degrade performance.

Tokenization influences model efficiency and accuracy significantly. Word-based tokenization can be inefficient due to large vocabulary sizes, while character-based methods lead to longer input sequences. Subword tokenization, such as Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE), strikes a balance by merging frequently occurring character pairs until the vocabulary reaches a pre-defined size. BPE iteratively refines the vocabulary, representing rare or unknown words as combinations of subwords, thus mitigating the OOV issue effectively.

Word-based tokenization treats each word as an atomic unit. In Rust, a simple implementation might use regex for word boundary detection. The following example uses regex to split text into individual words, handling case normalization and punctuation removal.

use regex::Regex;

fn word_tokenize(text: &str) -> Vec<String> {

let re = Regex::new(r"\b\w+\b").unwrap();

re.find_iter(text)

.map(|mat| mat.as_str().to_lowercase())

.collect()

}

fn main() {

let text = "Hello, Rust world! How are you today?";

let tokens = word_tokenize(text);

println!("Word tokens: {:?}", tokens);

}

This tokenizer captures each word while ignoring punctuation. Word-based tokenization is simple but can lead to large vocabularies and difficulties handling rare words.

Subword tokenization methods like BPE are common in modern NLP due to their efficient vocabulary size. In BPE, each character starts as an individual token, and the algorithm iteratively merges the most frequent pairs of characters, forming subwords. We illustrate a basic implementation of BPE below:

use std::collections::HashMap;

// Count frequencies of character pairs in tokens

fn count_pairs(tokens: &Vec<String>) -> HashMap<(String, String), usize> {

let mut pairs = HashMap::new();

for token in tokens.iter() {

let chars: Vec<String> = token.chars().map(|c| c.to_string()).collect();

for pair in chars.windows(2) {

let pair = (pair[0].clone(), pair[1].clone());

*pairs.entry(pair).or_insert(0) += 1;

}

}

pairs

}

// Merge the most frequent character pair

fn merge_most_frequent_pair(tokens: &mut Vec<String>, most_frequent: (String, String)) {

let merged = format!("{}{}", most_frequent.0, most_frequent.1);

for token in tokens.iter_mut() {

*token = token.replace(&format!("{} {}", most_frequent.0, most_frequent.1), &merged);

}

}

fn main() {

let mut tokens = vec!["l o w".to_string(), "l o w e r".to_string(), "n e w e s t".to_string()];

for _ in 0..10 {

let pairs = count_pairs(&tokens);

if let Some((most_frequent, _)) = pairs.iter().max_by_key(|&(_, freq)| freq) {

merge_most_frequent_pair(&mut tokens, most_frequent.clone());

}

}

println!("Tokens after BPE: {:?}", tokens);

}

This simplified BPE tokenizer iteratively merges the most common character pairs, reducing vocabulary size while preserving linguistic patterns within words.

Character-based tokenization segments text into individual characters, making it particularly useful for handling languages with complex morphology or large character sets. While this approach eliminates OOV words, it increases sequence length, requiring more computational power. Rust’s unicode-segmentation crate is useful for accurately handling Unicode characters in languages like Japanese or Chinese:

use unicode_segmentation::UnicodeSegmentation;

fn char_tokenize(text: &str) -> Vec<&str> {

UnicodeSegmentation::graphemes(text, true).collect()

}

fn main() {

let text = "你好,世界!";

let tokens = char_tokenize(text);

println!("Character tokens: {:?}", tokens);

}

The above example demonstrates Unicode-aware tokenization, which treats each character as a token. This approach is often applied in language models for text with highly diverse characters.

Vocabulary construction requires assembling tokens into a set that will serve as input for the model. To manage OOV terms, tokens that are not in the vocabulary can be replaced with a special UNK (unknown) token, or they can be represented through subword units using techniques like BPE.

In Rust, we can use HashMap to manage vocabulary indices and create mappings for efficient token-to-index conversion:

use std::collections::HashMap;

fn build_vocabulary(tokens: Vec<String>) -> HashMap<String, usize> {

let mut vocab = HashMap::new();

let mut idx = 0;

for token in tokens.iter() {

vocab.entry(token.clone()).or_insert_with(|| {

let index = idx;

idx += 1;

index

});

}

vocab

}

fn main() {

let tokens = vec![

"hello".to_string(),

"world".to_string(),

"hello".to_string(),

"rust".to_string(),

];

let vocab = build_vocabulary(tokens);

println!("Vocabulary: {:?}", vocab);

}

This code builds a vocabulary from a list of tokens by assigning each unique token an index. This approach is essential in training neural networks, where each token’s index corresponds to an embedding in the model.

Tokenization strategies are critical in applications where OOV handling, multilingual support, and efficiency are required. Subword tokenization, such as BPE and SentencePiece, has become a cornerstone of models like BERT and GPT-3, allowing them to scale without an excessively large vocabulary. For example, BERT’s WordPiece tokenization balances vocabulary size with linguistic diversity, allowing it to handle complex terms while keeping the model manageable.

Trends in tokenization are moving towards dynamic and adaptive tokenization techniques that can modify vocabulary based on the input domain or language. In multilingual and cross-lingual models like mBERT or XLM-R, tokenization models now seek to create universal vocabularies that reduce OOV rates across languages, especially for languages with overlapping alphabets or similar syntax. Additionally, neural tokenizers that can dynamically learn token boundaries are emerging, allowing models to adaptively tokenize without manual vocabulary design.

Through these tokenization techniques and Rust implementations, we lay the foundation for handling diverse language data in language model training. Each tokenization strategy has its trade-offs, from word-based methods for simplicity to subword and character-based methods for linguistic flexibility and OOV handling. The Rust ecosystem, with libraries like regex for word-based tokenization, unicode-segmentation for character handling, and custom implementations for subword tokenization, provides robust tools for building efficient and scalable language models tailored to diverse NLP applications.

9.4. Building the Model Architecture

Lets examine the architecture behind neural networks for language modeling, progressing from simple feedforward structures to advanced Transformer-based models. The architecture defines how information flows through the network, which is essential for capturing complex dependencies in language. This section introduces the evolution of model architectures, explains key neural network components, and explores attention mechanisms that have revolutionized large language models (LLMs).

Language modeling has evolved from basic feedforward networks to more complex architectures such as recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and Transformers, each designed to capture linguistic patterns in increasingly effective ways. The feedforward network is the most straightforward architecture, where input data passes through a series of layers, each consisting of neurons with weighted connections to those in the next layer. However, feedforward networks struggle with sequential data because they lack mechanisms to retain information across input sequences.

Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) address this limitation by introducing recurrent connections, allowing information from previous inputs to influence future states. For a sequence of inputs $x_1, x_2, \dots, x_T$, the hidden state $h_t$ at time $t$ depends not only on $x_t$ but also on $h_{t-1}$, encapsulating information from previous time steps. Mathematically, this is represented as:

$$h_t = \sigma(W_{xh} x_t + W_{hh} h_{t-1} + b_h)$$

where $W_{xh}$ and $W_{hh}$ are weight matrices, $b_h$ is a bias term, and $\sigma$ is a nonlinear activation function. RNNs excel in processing sequences but suffer from the vanishing gradient problem, making it difficult to retain long-term dependencies. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks address this with gating mechanisms, improving RNNs’ memory capabilities.

The Transformer architecture represents a breakthrough in sequence processing, especially for language modeling. By leveraging self-attention, Transformers eliminate the need for recurrence. Self-attention allows the model to assign different weights to each word in a sentence based on its relevance to other words. For an input sequence $X = [x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n]$, the self-attention mechanism computes the output $Z$ as:

$$Z = \text{softmax}\left(\frac{QK^T}{\sqrt{d_k}}\right)V$$

where $Q$, $K$, and $V$ are matrices derived from $X$ (representing queries, keys, and values), and $d_k$ is a scaling factor. This structure allows Transformers to capture context over long sequences more effectively than RNNs, making them the preferred architecture for modern LLMs.

A neural network’s performance depends heavily on its layers, activation functions, and loss functions. Layers organize neurons in a structured manner, with fully connected (dense) layers forming the backbone of feedforward and recurrent models, while attention layers are critical for Transformers. Activation functions introduce non-linearity, enabling networks to approximate complex functions. Common choices include ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit) for intermediate layers and softmax for output layers in classification tasks.

In language models, loss functions quantify the error in predictions, guiding the network’s learning through backpropagation. The most common choice for language modeling is cross-entropy loss, which measures the discrepancy between predicted probabilities and true labels. Mathematically, for a set of predicted probabilities $\hat{y}$ and true distribution $y$, the cross-entropy loss $L$ is:

$$L = -\sum_{i} y_i \log(\hat{y}_i)$$

Training a neural network involves updating weights to minimize the loss function, a process governed by backpropagation. During backpropagation, the loss is propagated backward through the network, adjusting weights based on their contribution to the error. This process uses gradient descent, where the weights are updated by moving in the opposite direction of the gradient of the loss function. Mathematically, the weight update $w_{ij}$ at each layer is calculated as:

$$w_{ij} \leftarrow w_{ij} - \eta \frac{\partial L}{\partial w_{ij}}$$

where $\eta$ is the learning rate, and $\frac{\partial L}{\partial w_{ij}}$ is the partial derivative of the loss with respect to $w_{ij}$. By iteratively applying backpropagation across training examples, the network adjusts its parameters to improve its predictions over time.

In Rust, using tch-rs, a feedforward network can be constructed by defining linear layers with ReLU activations. Here’s an example of a simple feedforward model for language modeling:

use tch::{nn, nn::Module, Device, Tensor};

fn main() {

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(Device::Cpu);

let net = nn::seq()

.add(nn::linear(&vs.root(), 128, 64, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(&vs.root(), 64, 32, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(&vs.root(), 32, 10, Default::default())); // Output layer

// Dummy input tensor

let input = Tensor::randn(&[128], (tch::Kind::Float, Device::Cpu)).view([-1, 128]);

let output = net.forward(&input);

println!("Feedforward Network Output: {:?}", output);

}

This simple model passes an input tensor through dense layers with ReLU activation functions, commonly used in early language models due to their efficiency in processing fixed-size inputs.

RNNs and LSTMs process sequences, which makes them suitable for language data. tch-rs provides RNN modules, including LSTM layers that improve memory retention over long sequences.

use tch::{nn, nn::RNN, Device, Tensor};

fn main() {

// Initialize variable store and define LSTM with input size 128 and hidden size 64

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(Device::Cpu);

let lstm = nn::lstm(&vs.root(), 128, 64, Default::default());

// Create a dummy input sequence of 10 timesteps with 128 features

let input = Tensor::randn(&[10, 1, 128], (tch::Kind::Float, Device::Cpu));

// Use the `seq` method to process the input sequence through the LSTM

let (output, _) = lstm.seq(&input);

// Print the output of the LSTM network

println!("LSTM Network Output: {:?}", output);

}

Here, the LSTM layer processes a sequence of inputs, each with 128 features, and outputs a tensor with 64 hidden states per timestep. LSTMs are useful for handling dependencies across long input sequences, but they can be computationally intensive and challenging to train on very long sequences.

The Transformer architecture is defined primarily by self-attention mechanisms and positional encoding. We demonstrate a simple self-attention layer in Rust.

use tch::{Tensor, Kind, Device}; // Import Device and remove unused import `nn`

fn scaled_dot_product_attention(q: &Tensor, k: &Tensor, v: &Tensor) -> Tensor {

let d_k = q.size()[1] as f64;

let scores = q.matmul(&k.transpose(-2, -1)) / d_k.sqrt(); // Borrow the transpose result

let weights = scores.softmax(-1, Kind::Float);

weights.matmul(v)

}

fn main() {

// Example query, key, and value tensors on CPU

let q = Tensor::randn(&[1, 64], (Kind::Float, Device::Cpu));

let k = Tensor::randn(&[1, 64], (Kind::Float, Device::Cpu));

let v = Tensor::randn(&[1, 64], (Kind::Float, Device::Cpu));

// Apply self-attention using scaled dot-product attention

let attention_output = scaled_dot_product_attention(&q, &k, &v);

println!("Self-Attention Output: {:?}", attention_output);

}

This function computes self-attention by calculating the dot product of q (queries) and k (keys), scaling by $\sqrt{d_k}$ for stability, applying softmax to get attention weights, and finally using these weights to transform v (values). This layer is foundational in Transformers, enabling models to capture relationships across tokens in a sequence.

Modern language models leverage Transformers because they outperform RNNs and LSTMs in capturing dependencies over long sequences. In applications like real-time translation, chatbots, and search engines, Transformers provide unparalleled accuracy and efficiency. The industry’s shift toward efficient Transformer variants, such as BERT and GPT, emphasizes context modeling and generalization, critical for applications that require precise language understanding.

The latest trends focus on efficient Transformers that reduce memory and computational demands without compromising performance. Models like DistilBERT and TinyBERT enable deployment on resource-constrained devices by reducing model size, which is especially valuable for edge devices. Innovations like sparse attention and low-rank factorization further enhance performance, making Transformer-based models more accessible for widespread use.

By implementing feedforward, RNN, and Transformer architectures in Rust, we demonstrate how different models capture patterns in language. Rust’s tch-rs library enables efficient and safe neural network operations, providing a foundation to experiment with complex architectures suited for real-world NLP applications. Each architecture has unique trade-offs, balancing memory efficiency, accuracy, and computational load, which are key considerations in designing effective language models.

9.5. Training the Language Model

Lets explore the intricacies of training a language model, a process that encompasses forward propagation, loss calculation, and backpropagation. This section examines essential optimization algorithms, addresses the importance of hyperparameter tuning, and covers strategies for mitigating overfitting and convergence issues. Training a language model requires a systematic approach to ensure it generalizes well to new data while avoiding issues like vanishing gradients, which can derail learning.

Training a neural network starts with forward propagation, where input data flows through each layer to produce predictions. In language modeling, forward propagation calculates the probability distribution over possible next tokens. For each token in a sequence, the model produces a prediction, and the sequence of predictions forms the basis for calculating the model’s loss. The goal is to minimize this loss, which quantifies the difference between the predicted and actual values.

The loss function measures prediction accuracy by assigning a cost to the discrepancy between predicted and true distributions. The most commonly used loss function in language modeling is cross-entropy loss, given by:

$$L = -\sum_{i=1}^N y_i \log(\hat{y}_i)$$

where $y_i$ is the true label, $\hat{y}_i$ is the model’s prediction, and $N$ represents the number of samples. Cross-entropy loss penalizes predictions far from the target, guiding the network’s learning toward improved accuracy.

After calculating the loss, we use backpropagation to compute the gradients, which measure how each weight in the network contributes to the loss. These gradients are then used to update weights in the direction that minimizes the loss. This is achieved through an optimization algorithm, which iteratively adjusts weights to reduce the model’s error.

Optimization algorithms determine how weights are updated, impacting both the speed and stability of training. Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) is one of the foundational algorithms, updating weights by computing gradients from a random subset (batch) of data. The update rule for SGD is given by:

$$w_{t+1} = w_t - \eta \cdot \nabla L(w_t)$$

where $w_t$ represents the weights at iteration ttt, η\\etaη is the learning rate, and $\nabla L(w_t)$ is the gradient of the loss with respect to the weights. While SGD is effective, it can be slow to converge and sensitive to the choice of learning rate.

The Adam optimizer is a widely-used alternative that combines elements of SGD with adaptive learning rates, making it more efficient for deep networks. Adam keeps track of both the mean and variance of the gradients, stabilizing updates. Its update rule for the weight vector $w$ is:

$$ m_t = \beta_1 m_{t-1} + (1 - \beta_1) \nabla L(w_t) $$

$$v_{t-1} + (1 - \beta_2) (\nabla L(w_t))^2$$

$$ \hat{m}_t = \frac{m_t}{1 - \beta_1^t}, \quad \hat{v}_t = \frac{v_t}{1 - \beta_2^t} $$

$$w_{t+1} = w_t - \eta \cdot \frac{\hat{m}_t}{\sqrt{\hat{v}_t} + \epsilon}$$

Here, $m_t$ and $v_t$ represent the mean and variance terms, while $\beta_1$ and $\beta_2$ are hyperparameters controlling decay rates. Adam’s adaptability and efficiency make it particularly suitable for language model training, especially in deep architectures like Transformers.

Hyperparameters significantly impact model performance and convergence. The learning rate (η\\etaη) controls step size during optimization. A high learning rate can lead to rapid but unstable learning, while a low rate yields stable but slow convergence. Batch size determines the number of samples processed before an update, impacting the balance between noise and speed in gradient estimation. A larger batch size reduces variance in updates but requires more memory. Finally, epochs define the number of passes through the dataset, with each epoch refining the model’s parameters. The balance of these hyperparameters is essential for achieving optimal convergence.

Training a language model requires managing overfitting (where the model learns noise rather than patterns) and underfitting (where it fails to capture the data’s structure). Regularization techniques, such as dropout, mitigate overfitting by randomly deactivating neurons during training, encouraging the model to learn more general features. Dropout is applied by multiplying neuron activations by a binary mask $M$ with dropout probability $p$:

$$h = M \cdot \text{ReLU}(Wx + b)$$

This mechanism forces the model to be less reliant on any specific neurons, leading to more robust generalization.

In Rust, using tch-rs, we can implement a training loop that includes forward pass, loss calculation, and backpropagation. Here’s a basic training loop example for a language model:

use tch::{nn, nn::Module, nn::OptimizerConfig, Tensor, Device};

fn main() {

// Initialize the variable store and define the model architecture

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(Device::Cpu);

let model = nn::seq()

.add(nn::linear(&vs.root(), 128, 64, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(&vs.root(), 64, 32, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(&vs.root(), 32, 10, Default::default()));

// Configure the Adam optimizer and mark it as mutable

let mut optimizer = nn::Adam::default().build(&vs, 1e-3).unwrap();

let mut train_loss = 0.0;

for epoch in 0..100 {

// Generate random input and target tensors

let inputs = Tensor::randn(&[10, 128], (tch::Kind::Float, Device::Cpu));

let targets = Tensor::randn(&[10, 10], (tch::Kind::Float, Device::Cpu));

// Forward pass and compute mean squared error loss

let output = model.forward(&inputs);

let loss = output.mse_loss(&targets, tch::Reduction::Mean);

// Convert the tensor loss to an f64 scalar and accumulate

train_loss += loss.double_value(&[]);

// Backward pass and optimization step

optimizer.backward_step(&loss);

// Print loss every 10 epochs

if epoch % 10 == 0 {

println!("Epoch: {}, Loss: {:?}", epoch, train_loss / 10.0);

train_loss = 0.0;

}

}

}

This code initializes a feedforward model with ReLU activations and trains it using the Adam optimizer. We compute the mean squared error loss, propagate the loss backward through the model, and adjust the weights. Monitoring the loss at each epoch helps evaluate model convergence.

Effective training requires monitoring model performance on validation data. Validation loss provides an indicator of generalization; if it diverges from training loss, the model may be overfitting. By tracking loss curves over epochs, we observe trends indicating whether the model is converging or encountering issues like vanishing or exploding gradients.

Vanishing gradients occur when gradients become exceedingly small, preventing effective weight updates in earlier layers. This is common in deep RNNs but less so in Transformers. Conversely, exploding gradients cause instability, often mitigated by gradient clipping, which caps gradients to prevent excessively large updates:

use tch::{nn, nn::Module, nn::OptimizerConfig, Tensor, Device, Kind, no_grad};

fn main() {

// Initialize the variable store and define the model architecture

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(Device::Cpu);

let model = nn::seq()

.add(nn::linear(&vs.root(), 128, 64, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(&vs.root(), 64, 32, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(&vs.root(), 32, 10, Default::default()));

// Configure the Adam optimizer and mark it as mutable

let mut optimizer = nn::Adam::default().build(&vs, 1e-3).unwrap();

let mut train_loss = 0.0;

let clip_norm = 0.5; // Define the gradient clipping norm

for epoch in 0..100 {

// Generate random input and target tensors

let inputs = Tensor::randn(&[10, 128], (Kind::Float, Device::Cpu));

let targets = Tensor::randn(&[10, 10], (Kind::Float, Device::Cpu));

// Forward pass and compute mean squared error loss

let output = model.forward(&inputs);

let loss = output.mse_loss(&targets, tch::Reduction::Mean);

// Convert the tensor loss to an f64 scalar and accumulate

train_loss += loss.double_value(&[]);

// Backward pass and gradient clipping

optimizer.zero_grad(); // Zero the gradients

loss.backward(); // Backpropagate

// Manually apply gradient clipping

no_grad(|| {

for param in vs.trainable_variables() {

let grad = param.grad();

let norm = grad.norm().double_value(&[]); // Calculate the gradient norm

if norm > clip_norm as f64 {

let scale = clip_norm / norm as f32;

let clipped_grad = grad * Tensor::from(scale); // Scale down the gradient

param.grad().copy_(&clipped_grad); // Copy the clipped gradient back

}

}

});

optimizer.step(); // Update parameters

// Print loss every 10 epochs

if epoch % 10 == 0 {

println!("Epoch: {}, Loss: {:?}", epoch, train_loss / 10.0);

train_loss = 0.0;

}

}

}

Training large language models is essential in industries requiring robust language understanding, such as conversational AI, search engines, and recommendation systems. Innovations in training methodologies, such as distributed training and mixed precision training, have improved the efficiency and feasibility of training massive LLMs like GPT-3 and BERT. Distributed training uses multiple GPUs or TPUs to accelerate training, while mixed precision training leverages lower precision (e.g., float16) to reduce memory consumption without sacrificing accuracy.

The trend towards self-supervised learning has transformed LLM training. By training on vast, unannotated datasets, models learn general language patterns, which can then be fine-tuned on specific tasks. Techniques like curriculum learning, which starts training on simpler data and gradually introduces complex examples, help stabilize training and improve model robustness.

This section covers essential techniques for implementing, optimizing, and monitoring the training process in Rust. By balancing optimization strategies, handling convergence issues, and evaluating performance, we create a model that learns efficiently and generalizes effectively, laying a foundation for building and training LLMs in Rust.

9.6. Evaluating and Fine-Tuning the Model

Lets discuss the processes of evaluating and fine-tuning a language model. Evaluation is essential to gauge a model’s ability to generalize and perform on specific tasks, using metrics such as perplexity, accuracy, and BLEU score. Fine-tuning, which adapts pre-trained models to specific domains, enhances model performance for tasks like text classification, sentiment analysis, and other natural language processing (NLP) applications. This section explains key evaluation metrics, explores the complexities of language model assessment, and demonstrates fine-tuning techniques to optimize model effectiveness across different tasks.