Chapter 12

Efficient Training Techniques

"Efficiency in AI training is not just about faster computations—it’s about smarter algorithms, better resource management, and innovative optimizations that push the boundaries of what’s possible." — Andrew Ng

Chapter 12 of LMVR delves into the techniques and strategies for efficiently training large language models using Rust. The chapter begins by emphasizing the importance of resource utilization, time, and cost in the training process, introducing key concepts such as parallelism, distributed training, and hardware acceleration. It covers the implementation of parallelism and concurrency in Rust, explores distributed training strategies, and discusses hardware-specific optimizations, including GPU and TPU integration. The chapter also examines the role of optimization algorithms, profiling, and real-time monitoring in enhancing training efficiency. Through practical implementations and case studies, the chapter provides a comprehensive guide to leveraging Rust’s features for scalable and efficient LLM training.

12.1. Introduction to Efficient Training

Efficient training of large language models (LLMs) is essential for optimizing resource utilization, reducing costs, and minimizing training time. As LLMs grow in size and complexity, the resources needed for training, including hardware, time, and energy, increase exponentially. Efficient training practices ensure that these resources are used strategically, balancing computational demands with budget and time constraints. This chapter introduces critical efficiency concepts such as parallelism, distributed training, and hardware acceleration, each of which plays a pivotal role in accelerating training processes without compromising model performance. In the context of Rust, which is optimized for speed and memory efficiency, implementing these techniques is particularly impactful, as Rust’s low-level control allows developers to maximize the hardware capabilities of GPUs, TPUs, or even multi-core CPUs, making it well-suited for high-performance training environments.

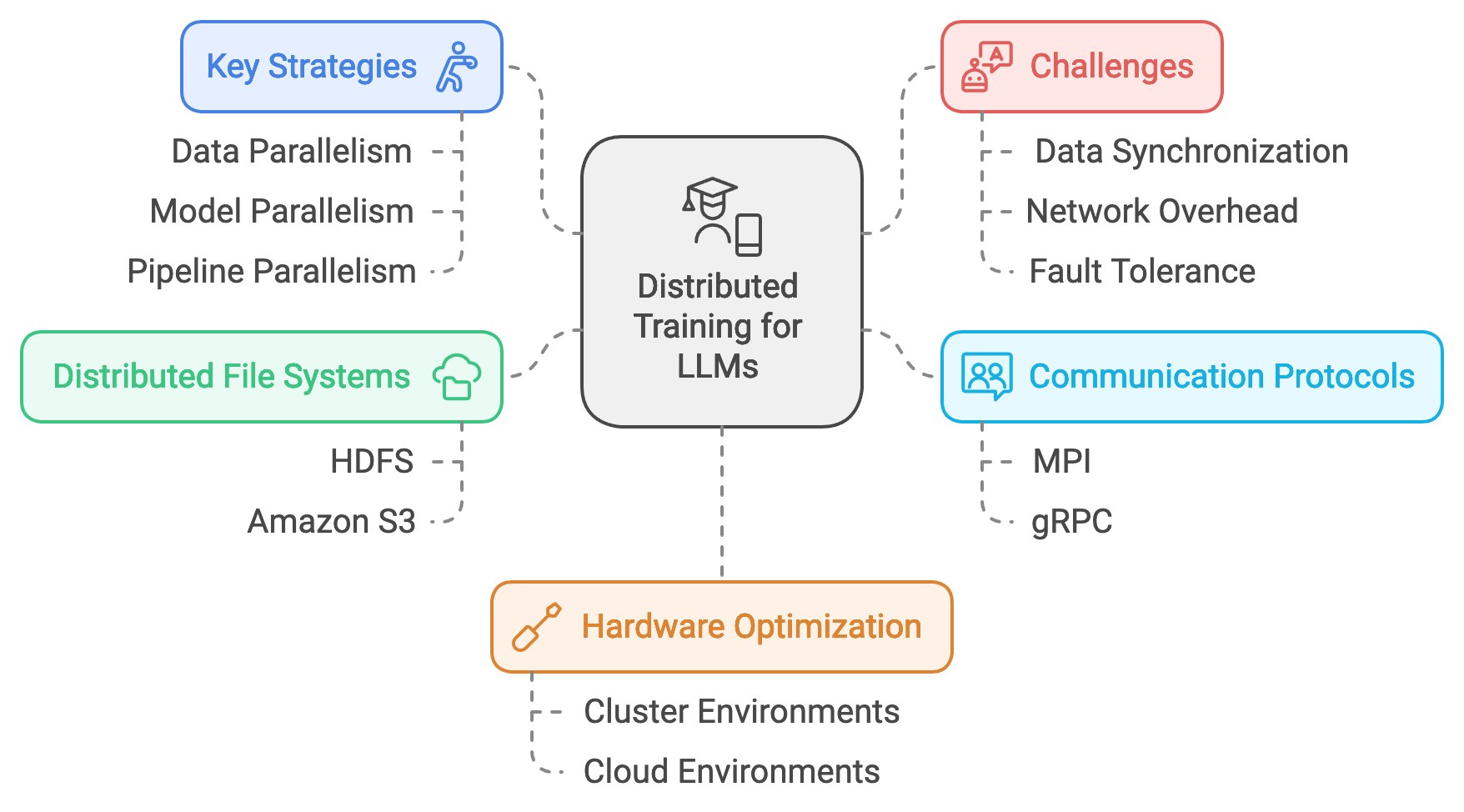

Figure 1: Optimization of LLM training.

Training LLMs requires handling vast datasets and intricate model architectures that are computationally intensive and demand high scalability. Parallelism, for instance, is essential in breaking down the training workload across multiple processors, allowing the model to be trained on different data subsets or portions of the model architecture simultaneously. In data parallelism, the same model is trained on separate data batches across multiple devices, synchronizing gradients after each step to ensure consistency. Model parallelism, by contrast, divides the model itself across devices, making it feasible to train models that exceed the memory capacity of a single device. Distributed training goes a step further, scaling across clusters of devices or nodes, essential for training the largest LLMs with billions of parameters. Rust’s memory management and concurrency support provide an edge in implementing these techniques, as they ensure reliable, low-latency communication between devices and efficient memory allocation for data parallelism and model partitioning.

There are inherent trade-offs between training speed and model accuracy. Reducing the time required for training often involves adjustments like smaller batch sizes or lower precision formats, which can introduce challenges in model convergence or degrade accuracy. However, efficient optimization techniques can help maintain a balance, allowing for high-speed training without sacrificing performance. Techniques like mixed-precision training, which uses both high- and low-precision data formats, reduce memory requirements and increase processing speed. Additionally, advanced gradient accumulation techniques allow effective large-batch training without needing extensive memory. By understanding these trade-offs, developers can tailor the training process to meet their specific requirements, optimizing for either speed, accuracy, or a balance of both.

Hardware-aware optimization is also critical in efficient training, especially for leveraging GPUs and TPUs. These processors are optimized for parallel computations, which is essential for matrix operations that underpin LLM training. Rust’s compatibility with CUDA for GPUs and XLA (Accelerated Linear Algebra) for TPUs provides a framework for harnessing these hardware accelerations effectively. By tailoring code to work within the architectural strengths of GPUs and TPUs, developers can ensure that each operation runs as efficiently as possible. This hardware-aware approach is especially valuable for LLMs, where extensive floating-point operations can benefit from parallelized execution and specialized data processing cores on GPUs and TPUs. Rust’s high-performance capabilities enable these computations to run smoothly, reducing overall training time and increasing throughput.

Setting up a Rust environment optimized for efficient LLM training involves selecting specific crates and configuring the toolchain for performance. This Rust code demonstrates a simple neural network training loop using the tch-rs crate, which provides bindings for PyTorch in Rust. The program creates a synthetic dataset, initializes a model with randomly generated weights, and trains it using the Adam optimizer over multiple epochs. The neural network model performs a matrix multiplication to make predictions, and the training loop minimizes the mean squared error loss by adjusting model weights through backpropagation.

[dependencies]

tokenizers = "0.20.1"

tch = "0.12.0"

use tch::{nn, nn::OptimizerConfig, Device, Tensor, Kind};

use std::error::Error;

// Dummy Model struct

struct Model {

weight: Tensor,

}

impl Model {

fn new(vs: &nn::Path, input_dim: i64, output_dim: i64) -> Self {

// Initialize model parameters with matching dimensions and mean/stdev

let weight = vs.randn("weight", &[input_dim, output_dim], 0.0, 1.0).set_requires_grad(true);

Self { weight }

}

fn forward(&self, inputs: &Tensor) -> Result<Tensor, Box<dyn Error>> {

// Forward function with correct dimensions

Ok(inputs.matmul(&self.weight))

}

fn backward(&self, loss: &Tensor) -> Result<(), Box<dyn Error>> {

// Calculate gradients

loss.backward();

Ok(())

}

}

// Synthetic Dataset struct

struct SyntheticDataset {

num_samples: usize,

input_dim: i64,

target_dim: i64,

}

impl SyntheticDataset {

fn new(num_samples: usize, input_dim: i64, target_dim: i64) -> Self {

Self {

num_samples,

input_dim,

target_dim,

}

}

fn batch(&self, batch_size: i64) -> Vec<Batch> {

(0..self.num_samples as i64 / batch_size)

.map(|_| {

// Generate random input and target tensors

let inputs = Tensor::randn(&[batch_size, self.input_dim], (Kind::Float, Device::Cpu));

let targets = Tensor::randn(&[batch_size, self.target_dim], (Kind::Float, Device::Cpu));

Batch { inputs, targets }

})

.collect()

}

}

// Struct to represent a batch of data

struct Batch {

inputs: Tensor,

targets: Tensor,

}

// Compute the Mean Squared Error loss

fn compute_loss(predictions: &Tensor, targets: &Tensor) -> Result<Tensor, Box<dyn Error>> {

let diff = predictions - targets;

let squared_diff = diff.pow_tensor_scalar(2); // Element-wise square

Ok(squared_diff.mean(Kind::Float)) // Compute the mean

}

fn main() -> Result<(), Box<dyn Error>> {

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(Device::Cpu); // VarStore for managing model parameters

let input_dim = 10;

let target_dim = 10;

let model = Model::new(&vs.root(), input_dim, target_dim);

let mut optimizer = nn::Adam::default().build(&vs, 1e-3)?; // Adam optimizer with learning rate 0.001

let dataset = SyntheticDataset::new(1000, input_dim, target_dim); // 1000 samples, input and target dim of 10

// Training loop with data parallelism (batch processing)

for epoch in 0..10 {

for batch in dataset.batch(32) {

let predictions = model.forward(&batch.inputs)?;

let loss = compute_loss(&predictions, &batch.targets)?;

// Backpropagation and optimization

model.backward(&loss)?;

optimizer.step();

optimizer.zero_grad();

}

println!("Epoch {} completed", epoch);

}

Ok(())

}

The code is structured around a custom Model struct that contains the network’s weights as a tensor, initialized to match the input and output dimensions. The Model struct has a forward method to compute predictions using matrix multiplication and a backward method to perform backpropagation. A SyntheticDataset struct generates random data batches for training, each with specified dimensions for inputs and targets. In the main training loop, the model makes predictions, computes the loss using mean squared error, and updates the weights based on gradients. The code iterates over multiple epochs, processing each batch and adjusting weights to minimize the error between predictions and targets.

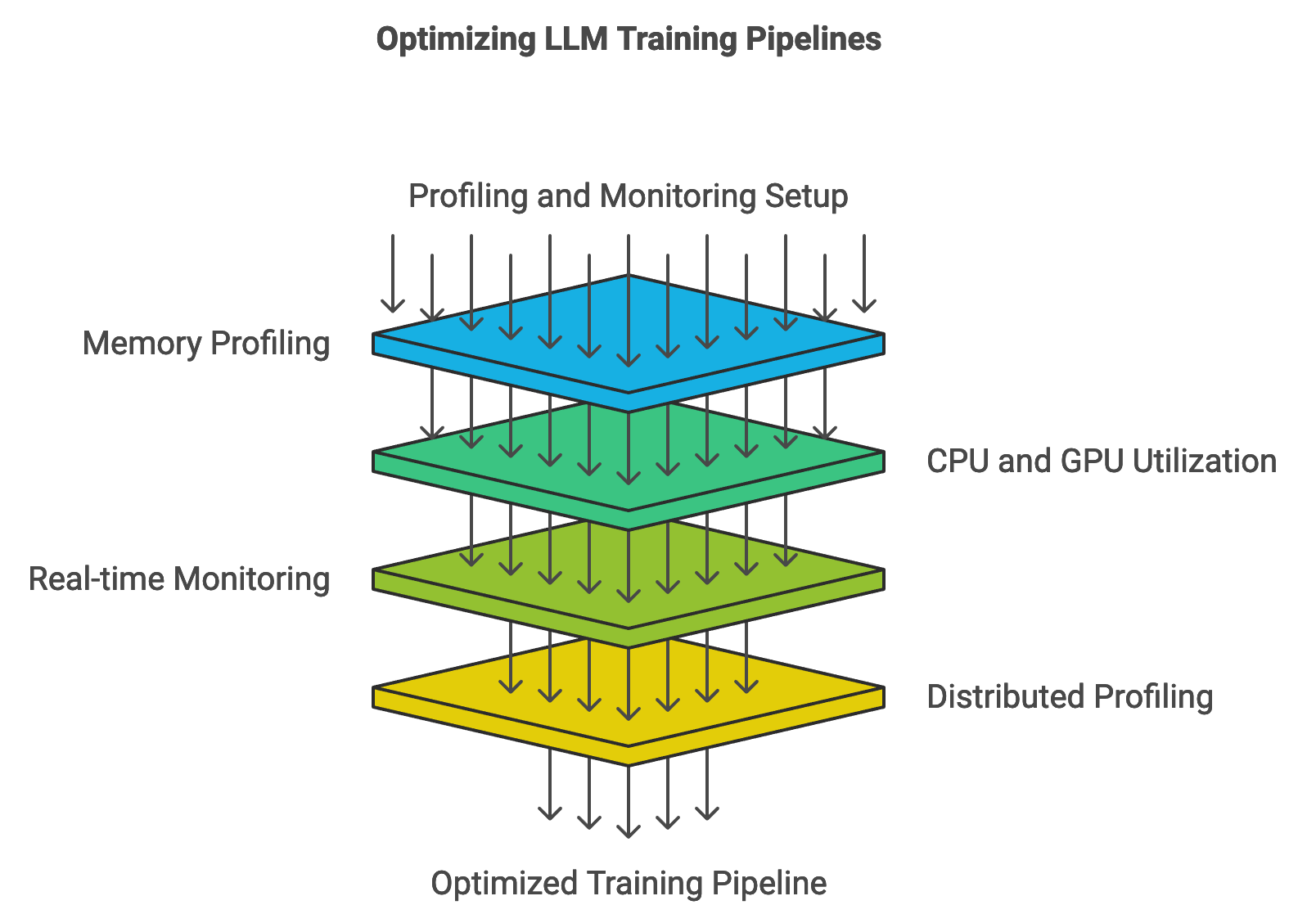

Identifying bottlenecks in the training process is crucial for optimization. In Rust, developers can utilize profiling tools to identify areas where processing lags, such as inefficient memory allocation, I/O delays, or CPU-GPU communication overheads. For instance, profiling may reveal that data loading is slower than model computation, prompting the use of data caching or parallel data loading to reduce latency. Rust’s memory control allows developers to fine-tune data transfers and device synchronization, streamlining the training pipeline and ensuring consistent throughput across hardware.

Industry use cases of efficient training in Rust demonstrate the impact of these techniques on real-world applications. For example, companies developing language-based recommendation systems can benefit from accelerated training, as fast model updates allow them to incorporate recent user interactions and preferences into recommendations. In finance, where rapid analysis of market data is required, efficiently trained LLMs enable firms to generate timely insights, providing a competitive advantage. Trends in efficient training emphasize using mixed-precision, distributed parallelism, and custom hardware (e.g., TPUs), which are supported by Rust’s performance-optimized libraries and concurrency handling. By staying updated on these trends, developers can leverage Rust’s potential to achieve robust, efficient training pipelines for large-scale language models.

In conclusion, efficient training of LLMs involves a strategic approach that balances resource utilization, accuracy, and scalability. Rust’s low-level control and memory efficiency make it uniquely suited for developing high-performance, scalable training environments, from batch processing to complex parallelism across multiple devices. As the demand for LLMs continues to grow, efficient training practices will be essential for sustaining advancements in natural language processing, allowing companies to innovate while managing costs and resource constraints effectively.

12.2. Parallelism and Concurrency in Rust

Parallelism and concurrency are essential in accelerating the training of large models by enabling multiple computations to be processed simultaneously. Parallelism in model training involves splitting the data or model structure across multiple processing units, allowing computations to occur independently or concurrently. Concurrency, on the other hand, refers to managing multiple tasks within the same time frame, leveraging asynchronous operations to handle high-throughput workloads without overloading any single processor. Rust’s concurrency model, including its support for threads, async/await syntax, and parallel iterators, is particularly suited for such tasks due to its emphasis on safety, memory management, and low-level performance control.

Rust provides a range of tools for implementing parallelism, including threads, async/await, and dedicated libraries such as rayon and tokio. Threads enable parallel execution by creating separate processing pathways for tasks, while async/await is used to manage asynchronous tasks without blocking, which is crucial in training pipelines where I/O operations and computations need to occur without stalling the main process. The rayon crate, for example, simplifies parallel processing by offering parallel iterators that allow for efficient distribution of batch processing, an essential technique in data parallelism. Meanwhile, tokio provides a robust framework for asynchronous tasks, which is especially beneficial when managing networked or distributed training processes across multiple devices or nodes.

Data parallelism and model parallelism are two primary methods for parallelizing model training. In data parallelism, multiple copies of the same model are distributed across different devices or threads, and each copy processes a separate batch of data. The outputs are then aggregated, and gradients are synchronized to ensure consistency across model replicas. Mathematically, if a model $M$ is trained on data $D$, data parallelism distributes batches $D_1, D_2, \ldots, D_n$ across $n$ devices, where each device computes gradients independently as $\nabla M(D_i)$. These gradients are averaged across all devices to update model parameters, maintaining uniformity in the training process.

Model parallelism, by contrast, divides the model itself across multiple devices or threads, allowing different parts of the model to compute in parallel. For instance, in a deep neural network with layers $L_1, L_2, \ldots, L_k$, one device may process layers $L_1$ through $L_{k/2}$ while another processes $L_{k/2+1}$ through $L_k$. This technique is useful for training models that exceed the memory capacity of a single device, as it distributes the model’s storage and computational load. Rust’s ownership model and concurrency controls ensure memory safety and prevent data races, which are essential for parallelism where model components or data batches are processed simultaneously.

Rayon is a data parallelism library for Rust that enables easy and efficient parallel processing using high-level abstractions. By leveraging Rayon, developers can transform standard Rust iterators into parallel iterators, which automatically distribute tasks across available CPU cores. This process allows applications to speed up tasks that can be processed concurrently, like batch computations, without manually handling thread management, locking, or load balancing. Rayon is particularly useful in computational workloads, such as machine learning, where tasks can often be split across data chunks and processed in parallel.

The rayon crate simplifies data parallelism by enabling parallel iterators, which automatically distribute tasks across available threads. This feature is especially useful in batch processing, where data can be divided into smaller subsets and processed in parallel, speeding up the training loop. The following Rust code demonstrates data parallelism using rayon, where each batch in the dataset is processed concurrently to accelerate training:

use ndarray::{Array, Array1, Array2, ArrayView2, Axis};

use ndarray_rand::rand_distr::Uniform;

use ndarray_rand::RandomExt;

use rayon::prelude::*; // Import Rayon for parallel iterators

use std::sync::Mutex; // Import Mutex to manage shared access

use std::time::Instant;

// Hyperparameters

const INPUT_SIZE: usize = 10;

const HIDDEN_SIZE: usize = 5;

const OUTPUT_SIZE: usize = 1;

const BATCH_SIZE: usize = 64;

const LEARNING_RATE: f32 = 0.01;

const EPOCHS: usize = 100;

// Neural Network struct

struct NeuralNetwork {

w1: Array2<f32>,

w2: Array2<f32>,

b1: Array1<f32>,

b2: Array1<f32>,

}

impl NeuralNetwork {

fn new() -> Self {

let w1 = Array::random((INPUT_SIZE, HIDDEN_SIZE), Uniform::new(-1.0, 1.0));

let w2 = Array::random((HIDDEN_SIZE, OUTPUT_SIZE), Uniform::new(-1.0, 1.0));

let b1 = Array::zeros(HIDDEN_SIZE);

let b2 = Array::zeros(OUTPUT_SIZE);

Self { w1, w2, b1, b2 }

}

fn forward(&self, x: ArrayView2<f32>) -> Array2<f32> {

let hidden = (x.dot(&self.w1) + &self.b1).map(|v| v.max(0.0)); // ReLU activation

hidden.dot(&self.w2) + &self.b2 // Output layer (no activation for regression)

}

fn backward(&mut self, x: ArrayView2<f32>, y: ArrayView2<f32>, output: ArrayView2<f32>) {

let error = &output - &y;

let hidden = (x.dot(&self.w1) + &self.b1).map(|v| v.max(0.0)); // Recalculate hidden layer

let hidden_grad = hidden.map(|&v| if v > 0.0 { 1.0 } else { 0.0 }); // Derivative of ReLU

// Calculate gradients for the second layer

let d_w2 = hidden.t().dot(&error) / x.shape()[0] as f32;

let d_b2 = error.sum_axis(Axis(0)) / x.shape()[0] as f32;

// Backpropagate the error to the first layer

let d_hidden = error.dot(&self.w2.t()) * &hidden_grad;

let d_w1 = x.t().dot(&d_hidden) / x.shape()[0] as f32;

let d_b1 = d_hidden.sum_axis(Axis(0)) / x.shape()[0] as f32;

// Update weights and biases by scaling gradients with LEARNING_RATE

self.w2 -= &(d_w2 * LEARNING_RATE);

self.b2 -= &(d_b2 * LEARNING_RATE);

self.w1 -= &(d_w1 * LEARNING_RATE);

self.b1 -= &(d_b1 * LEARNING_RATE);

}

}

// Generate synthetic data

fn generate_synthetic_data(n: usize) -> (Array2<f32>, Array2<f32>) {

let x = Array::random((n, INPUT_SIZE), Uniform::new(-1.0, 1.0));

let y = x.sum_axis(Axis(1)).to_shape((n, OUTPUT_SIZE)).unwrap().to_owned(); // Target is sum of inputs

(x, y)

}

// Sequential training

fn train_sequential(nn: &mut NeuralNetwork, x_train: &Array2<f32>, y_train: &Array2<f32>) {

for epoch in 0..EPOCHS {

for (x_batch, y_batch) in x_train

.axis_chunks_iter(Axis(0), BATCH_SIZE)

.zip(y_train.axis_chunks_iter(Axis(0), BATCH_SIZE))

{

let output = nn.forward(x_batch.view());

nn.backward(x_batch.view(), y_batch.view(), output.view());

}

let output = nn.forward(x_train.view());

let loss = (&output - y_train).mapv(|x| x.powi(2)).mean().unwrap();

println!("Sequential Epoch: {}, Loss: {:.4}", epoch, loss);

}

}

// Parallel training with Rayon

fn train_parallel(nn: &Mutex<NeuralNetwork>, x_train: &Array2<f32>, y_train: &Array2<f32>) {

for epoch in 0..EPOCHS {

let batches: Vec<_> = x_train

.axis_chunks_iter(Axis(0), BATCH_SIZE)

.zip(y_train.axis_chunks_iter(Axis(0), BATCH_SIZE))

.collect();

// Process each batch in parallel using Rayon

batches.par_iter().for_each(|(x_batch, y_batch)| {

let output;

{

// Lock the network for forward pass and backward pass

let mut nn_locked = nn.lock().unwrap();

output = nn_locked.forward(x_batch.view());

nn_locked.backward(x_batch.view(), y_batch.view(), output.view());

}

});

// Evaluate loss

let nn_locked = nn.lock().unwrap(); // Lock once to evaluate the loss

let output = nn_locked.forward(x_train.view());

let loss = (&output - y_train).mapv(|x| x.powi(2)).mean().unwrap();

println!("Parallel Epoch: {}, Loss: {:.4}", epoch, loss);

}

}

fn main() {

let (x_train, y_train) = generate_synthetic_data(1000);

// Sequential training

let mut nn_sequential = NeuralNetwork::new();

let start_sequential = Instant::now();

train_sequential(&mut nn_sequential, &x_train, &y_train);

let duration_sequential = start_sequential.elapsed();

println!(

"\nSequential training took: {:.2?} seconds",

duration_sequential

);

// Parallel training with Rayon

let nn_parallel = Mutex::new(NeuralNetwork::new());

let start_parallel = Instant::now();

train_parallel(&nn_parallel, &x_train, &y_train);

let duration_parallel = start_parallel.elapsed();

println!(

"\nParallel training took: {:.2?} seconds",

duration_parallel

);

// Compare the performance

println!(

"\nSpeedup: {:.2}x",

duration_sequential.as_secs_f64() / duration_parallel.as_secs_f64()

);

}

In the code, we first define a simple neural network and train it both sequentially and in parallel using Rayon for comparison. We generate synthetic data as input and target values for training, and then create two training functions: train_sequential for sequential training and train_parallel for parallelized training with Rayon. The train_parallel function uses Rayon’s par_iter to process each batch concurrently by splitting the data into smaller, independent subsets. We use a Mutex to safely share the neural network instance across threads during the parallel update process. Both training versions are timed using Instant to measure and compare their performances, with a final speedup calculation to quantify the improvement achieved with parallelism.

Model parallelism is an essential approach for training large neural networks that cannot fit entirely on a single device. In model parallelism, different parts of the model are distributed across multiple devices (e.g., CPUs or GPUs), each handling a subset of computations. This method contrasts with data parallelism, where the entire model is replicated on each device, and each processes a subset of the data. In Rust, model parallelism can be implemented using the standard std::thread library, allowing each thread to independently process a model layer or group of operations. By dividing the model's computations among threads, we can leverage multi-core processors to achieve better resource utilization and potentially faster training times for large models.

use ndarray::{Array, Array2, Axis, s};

use ndarray_rand::rand_distr::Uniform;

use ndarray_rand::RandomExt;

use std::sync::{Arc, Mutex};

use std::thread;

use std::time::Instant;

// Define hyperparameters

const INPUT_SIZE: usize = 10;

const HIDDEN_SIZE: usize = 64;

const OUTPUT_SIZE: usize = 1;

const LEARNING_RATE: f32 = 0.01;

const BATCH_SIZE: usize = 64;

const EPOCHS: usize = 10;

// Define a basic neural network structure

struct NeuralNetwork {

w1: Arc<Mutex<Array2<f32>>>,

b1: Arc<Mutex<Array2<f32>>>,

w2: Arc<Mutex<Array2<f32>>>,

b2: Arc<Mutex<Array2<f32>>>,

}

impl NeuralNetwork {

fn new() -> Self {

let w1 = Array::random((INPUT_SIZE, HIDDEN_SIZE), Uniform::new(-0.5, 0.5));

let b1 = Array::zeros((1, HIDDEN_SIZE));

let w2 = Array::random((HIDDEN_SIZE, OUTPUT_SIZE), Uniform::new(-0.5, 0.5));

let b2 = Array::zeros((1, OUTPUT_SIZE));

NeuralNetwork {

w1: Arc::new(Mutex::new(w1)),

b1: Arc::new(Mutex::new(b1)),

w2: Arc::new(Mutex::new(w2)),

b2: Arc::new(Mutex::new(b2)),

}

}

fn forward_layer1(&self, x: &Array2<f32>) -> Array2<f32> {

let w1 = self.w1.lock().unwrap();

let b1 = self.b1.lock().unwrap();

(x.dot(&*w1) + &*b1).mapv(f32::tanh)

}

fn forward_layer2(&self, h1: &Array2<f32>) -> Array2<f32> {

let w2 = self.w2.lock().unwrap();

let b2 = self.b2.lock().unwrap();

h1.dot(&*w2) + &*b2

}

fn backward_layer1(&self, d_w1: Array2<f32>, d_b1: Array2<f32>) {

let mut w1 = self.w1.lock().unwrap();

let mut b1 = self.b1.lock().unwrap();

*w1 -= &(d_w1 * LEARNING_RATE);

*b1 -= &(d_b1 * LEARNING_RATE);

}

fn backward_layer2(&self, d_w2: Array2<f32>, d_b2: Array2<f32>) {

let mut w2 = self.w2.lock().unwrap();

let mut b2 = self.b2.lock().unwrap();

*w2 -= &(d_w2 * LEARNING_RATE);

*b2 -= &(d_b2 * LEARNING_RATE);

}

}

// Synthetic data generation

fn generate_synthetic_data(n: usize) -> (Array2<f32>, Array2<f32>) {

let x = Array::random((n, INPUT_SIZE), Uniform::new(0., 1.));

let y = x.sum_axis(Axis(1)).to_shape((n, OUTPUT_SIZE)).unwrap().to_owned();

(x, y)

}

// Model parallel training function

fn train_model_parallel(nn: Arc<NeuralNetwork>, x: &Array2<f32>, y: &Array2<f32>) {

let h1 = {

let nn = nn.clone();

nn.forward_layer1(x)

};

let output = {

let nn = nn.clone();

nn.forward_layer2(&h1)

};

// Calculate gradients

let error = &output - y;

let d_w2 = h1.t().dot(&error).to_owned();

let d_b2 = error.sum_axis(Axis(0)).to_shape((1, OUTPUT_SIZE)).unwrap().to_owned();

// Split updates across threads for model parallelism

let nn1 = nn.clone();

let nn2 = nn.clone();

let x_clone = x.clone();

let backward1_handle = thread::spawn(move || {

let d_hidden = error.dot(&nn2.w2.lock().unwrap().t()) * (1. - h1.mapv(|v| v.powi(2)));

let d_w1 = x_clone.t().dot(&d_hidden).to_owned();

let d_b1 = d_hidden.sum_axis(Axis(0)).to_shape((1, HIDDEN_SIZE)).unwrap().to_owned();

nn2.backward_layer1(d_w1, d_b1);

});

nn1.backward_layer2(d_w2, d_b2);

backward1_handle.join().unwrap();

}

fn main() {

let (x, y) = generate_synthetic_data(1000);

let nn = Arc::new(NeuralNetwork::new());

let start = Instant::now();

for _ in 0..EPOCHS {

for i in (0..x.len_of(Axis(0))).step_by(BATCH_SIZE) {

let end_idx = std::cmp::min(i + BATCH_SIZE, x.len_of(Axis(0))); // Ensure end index doesn't exceed array length

let x_batch = x.slice(s![i..end_idx, ..]).to_owned();

let y_batch = y.slice(s![i..end_idx, ..]).to_owned();

train_model_parallel(nn.clone(), &x_batch, &y_batch);

}

}

println!("Training completed in {:?}", start.elapsed());

}

The code demonstrates a basic implementation of model parallelism in Rust using threads. A simple neural network with two layers is defined, with weights and biases stored as shared resources across threads. Each epoch, the input batch is passed through two separate forward layers in sequence. The error is then computed to perform backpropagation, where gradients for each layer are computed independently. To enable parallelism, the gradients for the first and second layers are computed in separate threads using std::thread::spawn, updating the respective weights and biases asynchronously. This setup distributes the model computations for each layer across threads, allowing each part of the model to be trained independently. The main function generates synthetic data, iterates through epochs and batches, and applies model parallelism during training. Finally, it measures and outputs the total training time.

Implementing parallelism in Rust directly impacts training time and resource utilization. By distributing data and model components across multiple threads or devices, training processes can complete more rapidly without overburdening any single processor. Profiling tools like perf or tokio-tracing can be used to analyze thread activity, identify bottlenecks, and assess the impact of parallelism on training. Metrics such as CPU and GPU utilization, latency, and memory consumption are crucial indicators for determining how efficiently the system is using resources. Identifying these bottlenecks helps refine the parallelism strategy, optimizing performance further through load balancing or refining batch sizes.

Industry applications of parallelism in training have grown extensively, with fields like autonomous vehicles and finance benefiting from reduced training times. In autonomous systems, rapid model updates are crucial for integrating new sensor data and enhancing real-time decision-making. Similarly, in finance, parallelism enables faster training on large transaction datasets, which is essential for fraud detection and predictive analytics. Emerging trends include hybrid parallelism strategies, which combine data and model parallelism to optimize for large-scale distributed training, an area where Rust’s performance and concurrency capabilities can be fully leveraged.

In conclusion, parallelism and concurrency are transformative in training large models, enabling faster, more efficient use of hardware resources. Rust’s robust concurrency model, combined with crates like rayon and tokio, provides a powerful framework for implementing parallelism safely and effectively. By distributing both data and model components across multiple threads or devices, Rust-based systems can achieve high-performance training, pushing the boundaries of scalability and efficiency in large language models and other complex AI systems.

12.3. Distributed Training Techniques

Distributed training has become a cornerstone for scaling large language models (LLMs) to handle expansive datasets and highly complex architectures. By distributing the workload across multiple devices or nodes, distributed training enables substantial acceleration of model training and allows for larger models that would be challenging to train on a single machine. Key strategies in distributed training include data parallelism, model parallelism, and pipeline parallelism, each with specific use cases and performance implications. Data parallelism, for instance, divides the dataset across nodes with each node holding a replica of the model, while model parallelism splits the model itself, allowing each node to process a different part of the architecture. Pipeline parallelism chains parts of the model across nodes, processing data sequentially in a pipeline fashion, enabling efficient memory and computational load distribution.

Figure 2: Distributed training strategy for LLMs.

Communication protocols and tools are central to distributed training, as nodes need to synchronize data and gradients during training. MPI (Message Passing Interface) is a widely-used protocol that facilitates communication across nodes, managing data transmission effectively in high-performance environments. Similarly, gRPC (Google Remote Procedure Call) is commonly used in cloud-based settings, enabling fast and reliable communication between nodes across distributed clusters. These tools allow for data sharing, synchronization, and collective operations like gradient averaging, essential for maintaining consistency during distributed training.

Distributed training introduces several challenges, including data synchronization, network communication overhead, and fault tolerance. Data synchronization ensures that updates from each node are aggregated consistently, especially when using data parallelism, where gradient accumulation must be precise across replicas to avoid inconsistencies. Network communication overhead can become significant as model size and node count increase, potentially slowing down training. Strategies such as gradient compression and asynchronous updates can mitigate some of these issues by reducing the amount of data transmitted or allowing nodes to operate independently without waiting for synchronization. Fault tolerance is another key consideration in distributed setups, as node failures can disrupt training. To address this, redundancy strategies and checkpointing ensure that training can resume from a recent state without loss of progress.

Distributed file systems and data sharding play a crucial role in managing large datasets across multiple nodes. Distributed file systems, such as Hadoop Distributed File System (HDFS) or Amazon S3, provide scalable storage solutions that allow nodes to access data concurrently, reducing bottlenecks associated with I/O operations. Data sharding divides the dataset into smaller, manageable pieces stored across nodes, enhancing read and write efficiency and ensuring that data is readily available to each node. This setup is essential for handling large datasets typical in LLM training, where data must be processed quickly and efficiently to keep up with the computational demands of distributed training.

Optimizing distributed training for different hardware setups requires consideration of hardware-specific configurations and performance constraints. In cluster environments, low-latency, high-bandwidth networks are critical, as nodes communicate frequently during synchronization. Distributed training in cloud environments, meanwhile, benefits from elasticity, where computational resources scale dynamically based on training demands. Selecting the right configuration for distributed training depends on factors such as the model size, the dataset, and the desired level of scalability. For example, hardware setups with high inter-node communication costs may benefit more from asynchronous updates, reducing the dependency on synchronization.

In deep learning, parallelism is crucial for efficiently training models, especially when handling large datasets or complex models that demand significant computational resources. Two primary types of parallelism used in neural networks are data parallelism and model parallelism. Data parallelism involves splitting data across multiple devices or processing units, allowing each to perform computations independently before synchronizing the results. This approach works well when the model fits entirely within each device's memory. However, model parallelism becomes essential when the model is too large to fit on a single device, especially for layers with a vast number of parameters.

In model parallelism, different parts of the model are distributed across separate devices or processing units. Each part computes a distinct subset of the model’s operations, and intermediate results are passed between them. This allows for the distribution of a model’s components across multiple resources, alleviating memory constraints on a single device. Although model parallelism can introduce communication overhead when transferring data between different parts of the model, it is often the only feasible way to train massive neural networks that exceed the capacity of a single device’s memory.

use ndarray::{Array, Array2, Axis, s};

use ndarray_rand::rand_distr::Uniform;

use ndarray_rand::RandomExt;

use std::sync::{Arc, Mutex};

use std::thread;

use std::time::Instant;

// Define hyperparameters

const INPUT_SIZE: usize = 10;

const HIDDEN_SIZE: usize = 64;

const OUTPUT_SIZE: usize = 1;

const LEARNING_RATE: f32 = 0.01;

const BATCH_SIZE: usize = 64;

const EPOCHS: usize = 10;

// Define a basic neural network structure

struct NeuralNetwork {

w1: Arc<Mutex<Array2<f32>>>,

b1: Arc<Mutex<Array2<f32>>>,

w2: Arc<Mutex<Array2<f32>>>,

b2: Arc<Mutex<Array2<f32>>>,

}

impl NeuralNetwork {

fn new() -> Self {

let w1 = Array::random((INPUT_SIZE, HIDDEN_SIZE), Uniform::new(-0.5, 0.5));

let b1 = Array::zeros((1, HIDDEN_SIZE));

let w2 = Array::random((HIDDEN_SIZE, OUTPUT_SIZE), Uniform::new(-0.5, 0.5));

let b2 = Array::zeros((1, OUTPUT_SIZE));

NeuralNetwork {

w1: Arc::new(Mutex::new(w1)),

b1: Arc::new(Mutex::new(b1)),

w2: Arc::new(Mutex::new(w2)),

b2: Arc::new(Mutex::new(b2)),

}

}

fn forward_layer1(&self, x: &Array2<f32>) -> Array2<f32> {

let w1 = self.w1.lock().unwrap();

let b1 = self.b1.lock().unwrap();

(x.dot(&*w1) + &*b1).mapv(f32::tanh)

}

fn forward_layer2(&self, h1: &Array2<f32>) -> Array2<f32> {

let w2 = self.w2.lock().unwrap();

let b2 = self.b2.lock().unwrap();

h1.dot(&*w2) + &*b2

}

fn backward_layer1(&self, d_w1: Array2<f32>, d_b1: Array2<f32>) {

let mut w1 = self.w1.lock().unwrap();

let mut b1 = self.b1.lock().unwrap();

*w1 -= &(d_w1 * LEARNING_RATE);

*b1 -= &(d_b1 * LEARNING_RATE);

}

fn backward_layer2(&self, d_w2: Array2<f32>, d_b2: Array2<f32>) {

let mut w2 = self.w2.lock().unwrap();

let mut b2 = self.b2.lock().unwrap();

*w2 -= &(d_w2 * LEARNING_RATE);

*b2 -= &(d_b2 * LEARNING_RATE);

}

}

// Synthetic data generation

fn generate_synthetic_data(n: usize) -> (Array2<f32>, Array2<f32>) {

let x = Array::random((n, INPUT_SIZE), Uniform::new(0., 1.));

let y = x.sum_axis(Axis(1)).to_shape((n, OUTPUT_SIZE)).unwrap().to_owned();

(x, y)

}

// Model parallel training function

fn train_model_parallel(nn: Arc<NeuralNetwork>, x: &Array2<f32>, y: &Array2<f32>) {

let h1 = {

let nn = nn.clone();

nn.forward_layer1(x)

};

let output = {

let nn = nn.clone();

nn.forward_layer2(&h1)

};

// Calculate gradients

let error = &output - y;

let d_w2 = h1.t().dot(&error).to_owned();

let d_b2 = error.sum_axis(Axis(0)).to_shape((1, OUTPUT_SIZE)).unwrap().to_owned();

// Split updates across threads for model parallelism

let nn1 = nn.clone();

let nn2 = nn.clone();

let x_clone = x.clone();

let backward1_handle = thread::spawn(move || {

let d_hidden = error.dot(&nn2.w2.lock().unwrap().t()) * (1. - h1.mapv(|v| v.powi(2)));

let d_w1 = x_clone.t().dot(&d_hidden).to_owned();

let d_b1 = d_hidden.sum_axis(Axis(0)).to_shape((1, HIDDEN_SIZE)).unwrap().to_owned();

nn2.backward_layer1(d_w1, d_b1);

});

nn1.backward_layer2(d_w2, d_b2);

backward1_handle.join().unwrap();

}

fn main() {

let (x, y) = generate_synthetic_data(1000);

let nn = Arc::new(NeuralNetwork::new());

let start = Instant::now();

for epoch in 0..EPOCHS {

for i in (0..x.len_of(Axis(0))).step_by(BATCH_SIZE) {

let end_idx = std::cmp::min(i + BATCH_SIZE, x.len_of(Axis(0))); // Ensure end index doesn't exceed array length

let x_batch = x.slice(s![i..end_idx, ..]).to_owned();

let y_batch = y.slice(s![i..end_idx, ..]).to_owned();

train_model_parallel(nn.clone(), &x_batch, &y_batch);

}

println!("Epoch {} completed", epoch + 1);

}

println!("Training completed in {:?}", start.elapsed());

}

The code above implements basic model parallelism by dividing the forward and backward passes into separate threads. It defines a simple two-layer neural network with weights and biases encapsulated in an Arc structure for safe multi-threaded access. The first layer's computations (forward_layer1) run independently, producing intermediate results (h1) for the second layer. Gradients are then computed, and the updates are split across two threads. One thread handles the weight and bias updates for the second layer (backward_layer2), while another thread updates the parameters for the first layer (backward_layer1). This allows both layers' gradients to be calculated and applied in parallel, demonstrating a simplified model-parallel training setup in Rust.

Experimenting with different distributed training strategies provides insights into their impact on training performance. For example, synchronous updates, where nodes synchronize gradients after each step, ensure consistent model updates but can introduce delays in large setups with significant communication overhead. Asynchronous updates, by contrast, allow nodes to update their models independently, reducing synchronization delay but introducing potential inconsistencies in model updates. These strategies can be tested and compared in Rust, with performance metrics such as latency, accuracy, and throughput providing feedback on the most suitable approach for a given environment.

Deploying a distributed training pipeline on a cloud-based cluster allows for scalability and evaluation of the training setup in a production environment. Cloud platforms, such as AWS and Google Cloud, provide managed solutions for distributed training, with support for GPU and TPU clusters that can be dynamically scaled based on demand. By deploying the Rust-based distributed training pipeline on a cloud cluster, developers can evaluate its scalability and efficiency, optimizing resource allocation based on the computational needs of the model. Monitoring tools, such as Prometheus or Grafana, track resource utilization and latency, allowing fine-tuning of distributed strategies to achieve optimal performance.

Distributed training techniques are transformative in industries where rapid model updates and large-scale training are essential. In personalized content recommendations, for example, distributed training enables frequent model updates based on recent user interactions, enhancing recommendation relevance. In autonomous systems, where models require constant retraining on new sensor data, distributed training allows companies to scale effectively, accommodating the large datasets needed for real-time decision-making. Trends in distributed training focus on hybrid parallelism, combining data, model, and pipeline parallelism to optimize resource usage, and leveraging cloud infrastructure to support elastic scalability, areas where Rust’s performance and control offer distinct advantages.

In summary, distributed training techniques provide the foundation for scaling LLMs effectively, allowing them to leverage vast datasets and complex architectures. Rust’s concurrency support and low-level control make it particularly suitable for implementing distributed training, from data synchronization to communication management. By applying distributed file systems, data sharding, and cloud-based deployment, Rust-based distributed training pipelines can achieve high efficiency, reliability, and scalability, positioning them for advanced, production-grade machine learning applications.

12.4. Hardware Acceleration and Optimization

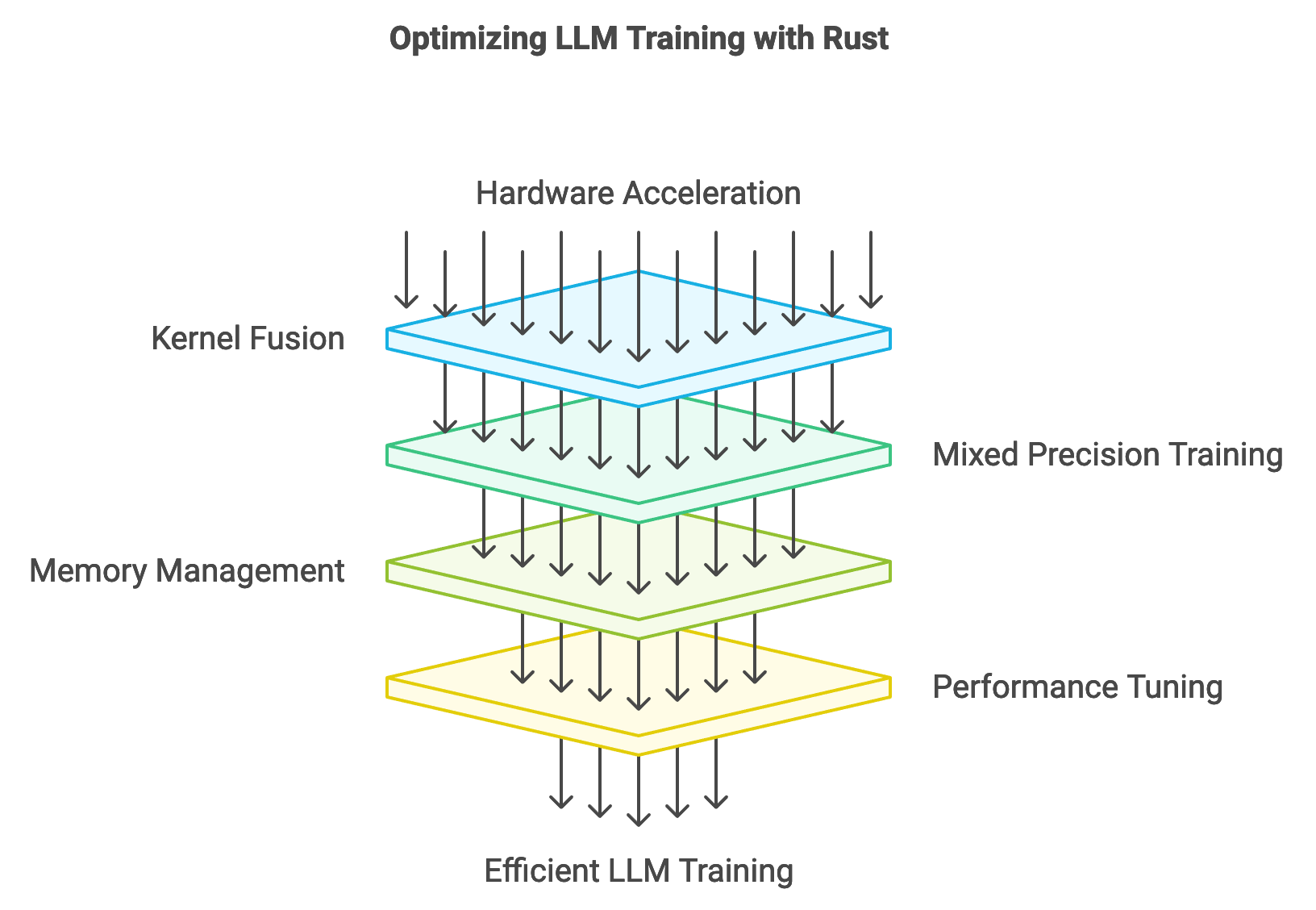

Hardware acceleration plays an essential role in training large language models (LLMs), where GPUs, TPUs, and custom accelerators provide the computational power needed for intensive matrix operations and parallelized data processing. Accelerators enable faster computations by leveraging specialized cores optimized for linear algebra operations common in neural network training. For example, GPUs excel in processing large batches of data simultaneously, while TPUs, designed explicitly for tensor operations, offer even higher efficiency for specific machine learning tasks. To harness this power, hardware-aware optimization techniques like kernel fusion, mixed precision training, and memory management are applied to maximize resource utilization and minimize bottlenecks in training pipelines. Rust’s ecosystem, with bindings to low-level libraries like CUDA for NVIDIA GPUs and ROCm for AMD GPUs, facilitates these optimizations, providing developers with the control needed to configure high-performance, hardware-optimized training.

Figure 3: Hardware acceleration strategy for LLM training.

Kernel fusion is a critical technique that combines multiple computation steps into a single kernel, reducing the number of memory access points and improving data flow within the processor. For example, consider two operations: element-wise addition and ReLU activation. By fusing these into a single kernel, the data only needs to be loaded and stored once, reducing memory access latency. Mathematically, kernel fusion can be represented as $Y = \text{ReLU}(X + W)$ where $X$ and $W$ are tensors. Instead of computing $Z = X + W$ followed by $Y = \text{ReLU}(Z)$, kernel fusion performs both operations in one pass. This is particularly advantageous on GPUs, where minimizing memory transactions significantly boosts performance, especially for large-scale models.

Mixed precision training, another hardware-aware optimization, reduces resource usage by combining lower-precision data types like FP16 (16-bit floating point) with higher-precision types (FP32) for critical calculations. This approach trades a minimal loss in precision for a substantial gain in processing speed and memory efficiency, enabling larger batch sizes and faster processing. Rust’s support for mixed precision is achieved through libraries that interface with CUDA and other acceleration libraries. During mixed precision training, calculations that don’t require high precision, like forward and backward propagation, are computed in FP16, while the final steps, like gradient updates, maintain FP32 precision to prevent numerical instability. The trade-offs in precision are carefully managed to ensure that model accuracy remains high while resource usage and computation times decrease, a critical balance for efficient LLM training.

Rust’s bindings to hardware-specific libraries like CUDA, ROCm, and OneAPI extend its utility for implementing such hardware-accelerated techniques, as these libraries expose low-level functionality that allows fine control over memory allocation, data transfers, and kernel operations. For example, using CUDA with Rust, developers can customize memory management through cuda-sys and cust, providing direct access to device memory, stream control, and kernel launches. This level of control is essential for LLMs, as they require vast memory and efficient data management to support their complex architectures.

Integrating hardware accelerators into Rust-based training pipelines presents challenges related to compatibility and performance tuning. Ensuring compatibility involves configuring Rust to work with various hardware libraries and ensuring that each operation executes with minimal latency. Performance tuning, meanwhile, involves profiling and adjusting kernel execution, data transfer rates, and memory usage, which are critical for maintaining throughput and reducing idle times on the GPU or TPU. By optimizing each step in the training pipeline, Rust-based systems can leverage the maximum potential of accelerators, ensuring that the training process remains efficient and scalable.

Mixed precision training and model parallelism are two significant advancements in deep learning that address the challenges of large models and computational efficiency. As neural networks grow in complexity, they demand more memory and computational power, often exceeding the capabilities of a single device or standard precision calculations. Mixed precision training leverages FP16 (half-precision) operations for forward passes and FP32 (single-precision) for backward passes. This approach optimizes memory usage, speeds up computations, and minimizes power consumption. By performing the forward pass in FP16, memory and computational requirements are reduced, allowing for faster training without significant loss in accuracy. The backward pass, which calculates gradients, remains in FP32 to maintain numerical stability in weight updates, which is crucial for converging to optimal solutions.

Model parallelism is another technique essential for managing large models that do not fit entirely on one device. Instead of using only data parallelism (where the dataset is split across devices), model parallelism splits the model's layers or components, enabling different devices or threads to process parts of the model simultaneously. This approach enhances efficiency and ensures that models can be trained even when they exceed single-device memory limits. By combining model parallelism with mixed precision training, we can achieve faster training for large models while managing hardware resources effectively.

use ndarray::{Array, Array2, Axis, s};

use ndarray_rand::rand_distr::Uniform;

use ndarray_rand::RandomExt;

use std::sync::{Arc, Mutex};

use std::thread;

use std::time::Instant;

use cust::memory::DeviceBuffer;

use cust::{CudaContext, CudaFlags};

// Define hyperparameters

const INPUT_SIZE: usize = 10;

const HIDDEN_SIZE: usize = 64;

const OUTPUT_SIZE: usize = 1;

const LEARNING_RATE: f32 = 0.01;

const BATCH_SIZE: usize = 64;

const EPOCHS: usize = 10;

struct NeuralNetwork {

w1: Arc<Mutex<DeviceBuffer<f16>>>,

b1: Arc<Mutex<DeviceBuffer<f16>>>,

w2: Arc<Mutex<DeviceBuffer<f16>>>,

b2: Arc<Mutex<DeviceBuffer<f16>>>,

}

impl NeuralNetwork {

fn new(context: &CudaContext) -> Self {

let w1 = DeviceBuffer::from_slice(

&Array::random((INPUT_SIZE, HIDDEN_SIZE), Uniform::new(-0.5, 0.5))

.mapv(|x| x as f16)

.into_raw_vec(),

)

.unwrap();

let b1 = DeviceBuffer::from_slice(

&Array::zeros((1, HIDDEN_SIZE)).mapv(|x| x as f16).into_raw_vec(),

)

.unwrap();

let w2 = DeviceBuffer::from_slice(

&Array::random((HIDDEN_SIZE, OUTPUT_SIZE), Uniform::new(-0.5, 0.5))

.mapv(|x| x as f16)

.into_raw_vec(),

)

.unwrap();

let b2 = DeviceBuffer::from_slice(

&Array::zeros((1, OUTPUT_SIZE)).mapv(|x| x as f16).into_raw_vec(),

)

.unwrap();

NeuralNetwork {

w1: Arc::new(Mutex::new(w1)),

b1: Arc::new(Mutex::new(b1)),

w2: Arc::new(Mutex::new(w2)),

b2: Arc::new(Mutex::new(b2)),

}

}

fn forward_layer1(&self, x: &Array2<f32>, context: &CudaContext) -> DeviceBuffer<f16> {

let w1 = self.w1.lock().unwrap();

let b1 = self.b1.lock().unwrap();

// Perform dot product and activation (FP16 precision)

// Implement CUDA kernel or use cuBLAS for matrix multiplication in FP16

// Placeholder - replace with actual CUDA operation

let h1 = x.dot(&*w1).mapv(f32::tanh).mapv(|v| v as f16);

DeviceBuffer::from_slice(&h1.into_raw_vec()).unwrap()

}

fn forward_layer2(&self, h1: &DeviceBuffer<f16>, context: &CudaContext) -> DeviceBuffer<f16> {

let w2 = self.w2.lock().unwrap();

let b2 = self.b2.lock().unwrap();

// Perform dot product (FP16 precision) and return FP16 output

// Placeholder - replace with actual CUDA operation

DeviceBuffer::from_slice(&[0.0f16; OUTPUT_SIZE]).unwrap() // Adjust with real operations

}

fn backward_layer1(&self, d_w1: Array2<f32>, d_b1: Array2<f32>) {

let mut w1 = self.w1.lock().unwrap();

let mut b1 = self.b1.lock().unwrap();

// Update weights (FP32 precision)

*w1 -= &(d_w1 * LEARNING_RATE) as f16;

*b1 -= &(d_b1 * LEARNING_RATE) as f16;

}

fn backward_layer2(&self, d_w2: Array2<f32>, d_b2: Array2<f32>) {

let mut w2 = self.w2.lock().unwrap();

let mut b2 = self.b2.lock().unwrap();

// Update weights (FP32 precision)

*w2 -= &(d_w2 * LEARNING_RATE) as f16;

*b2 -= &(d_b2 * LEARNING_RATE) as f16;

}

}

fn generate_synthetic_data(n: usize) -> (Array2<f32>, Array2<f32>) {

let x = Array::random((n, INPUT_SIZE), Uniform::new(0., 1.));

let y = x.sum_axis(Axis(1)).to_shape((n, OUTPUT_SIZE)).unwrap().to_owned();

(x, y)

}

fn train_model_parallel(nn: Arc<NeuralNetwork>, x: &Array2<f32>, y: &Array2<f32>, context: &CudaContext) {

let h1 = nn.forward_layer1(x, context);

let output = nn.forward_layer2(&h1, context);

// Calculate gradients in FP32 for stability

// Placeholder for CUDA kernel calls

let error = &output - y;

let d_w2 = h1.t().dot(&error).to_owned();

let d_b2 = error.sum_axis(Axis(0)).to_shape((1, OUTPUT_SIZE)).unwrap().to_owned();

let nn1 = nn.clone();

let nn2 = nn.clone();

let x_clone = x.clone();

let backward1_handle = thread::spawn(move || {

let d_hidden = error.dot(&nn2.w2.lock().unwrap().t()) * (1. - h1.mapv(|v| v.powi(2)));

let d_w1 = x_clone.t().dot(&d_hidden).to_owned();

let d_b1 = d_hidden.sum_axis(Axis(0)).to_shape((1, HIDDEN_SIZE)).unwrap().to_owned();

nn2.backward_layer1(d_w1, d_b1);

});

nn1.backward_layer2(d_w2, d_b2);

backward1_handle.join().unwrap();

}

fn main() {

let context = CudaContext::new(CudaFlags::SCHED_AUTO).unwrap();

let (x, y) = generate_synthetic_data(1000);

let nn = Arc::new(NeuralNetwork::new(&context));

let start = Instant::now();

for epoch in 0..EPOCHS {

for i in (0..x.len_of(Axis(0))).step_by(BATCH_SIZE) {

let end_idx = std::cmp::min(i + BATCH_SIZE, x.len_of(Axis(0)));

let x_batch = x.slice(s![i..end_idx, ..]).to_owned();

let y_batch = y.slice(s![i..end_idx, ..]).to_owned();

train_model_parallel(nn.clone(), &x_batch, &y_batch, &context);

}

println!("Epoch {} completed.", epoch + 1);

}

println!("Training completed in {:?}", start.elapsed());

}

The provided code demonstrates a basic neural network setup in Rust with mixed precision and model parallelism capabilities. The network weights and biases are stored as FP16 values on the GPU, utilizing cust (CUDA for Rust) and cuda-sys for GPU-based computations. In the forward_layer1 and forward_layer2 functions, forward passes are conducted in FP16, leveraging the speed and memory efficiency of half-precision operations. For the backward pass, gradients are computed in FP32 to maintain stability. The code distributes gradient calculations across threads, with each thread processing a component of the model independently. The train_model_parallel function handles this by launching separate threads to perform partial updates on different layers. After each epoch, it logs progress, tracking training time and epochs for performance assessment. Overall, this code exemplifies how mixed precision and model parallelism can be combined to accelerate training of neural networks using Rust and GPU resources.

Experimenting with hardware-specific optimizations, like kernel fusion and memory management, improves the performance of Rust-based training pipelines on GPUs. Kernel fusion, implemented in Rust through CUDA, reduces the number of memory transactions, minimizing latency. Memory management optimizations, like pre-allocating memory and caching data on the GPU, reduce I/O bottlenecks, allowing the model to process batches continuously without waiting for data transfers. Profiling tools in Rust can identify performance bottlenecks, such as idle GPU cores or inefficient memory access patterns, and guide adjustments in memory allocation or kernel configurations to achieve smoother training.

Benchmarking Rust-based training pipelines on different hardware setups allows for comparisons in training speed, accuracy, and resource utilization. For example, training on an NVIDIA A100 GPU versus a V100 GPU can reveal the impact of improved hardware support for mixed precision and memory bandwidth on training efficiency. Benchmarks also provide insights into which optimizations yield the most significant performance gains, such as the speed increase from mixed precision training on newer hardware or the latency reduction from kernel fusion on multi-GPU setups.

Hardware-accelerated training techniques have significant applications across various industries. In healthcare, accelerated model training enables faster development of predictive models for diagnostics, processing large datasets of medical records and images in real-time. In autonomous vehicles, hardware-optimized LLMs improve response times for systems processing complex sensor data streams, crucial for real-time decision-making. Trends in hardware acceleration focus on custom chip development, such as Google’s TPU and Amazon’s Trainium, which are optimized for AI workloads. These advancements, combined with Rust’s hardware control capabilities, make it a powerful language for implementing high-performance, hardware-aware AI systems.

In conclusion, hardware acceleration and optimization are pivotal for scaling LLM training effectively, and Rust’s robust support for CUDA, ROCm, and low-level memory management makes it an ideal environment for these tasks. By applying techniques like kernel fusion, mixed precision training, and customized memory management, Rust-based training pipelines can achieve substantial improvements in speed and resource efficiency. These optimizations not only enhance performance on GPUs and TPUs but also contribute to the broader adoption of Rust in machine learning, positioning it as a competitive choice for developing scalable, efficient AI systems.

12.5. Optimization Algorithms for Efficient Training

Optimization algorithms are essential for training large language models (LLMs), providing the techniques needed to iteratively adjust model parameters, minimize loss, and ultimately improve model accuracy. Popular optimization algorithms for LLMs include Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD), Adam, RMSprop, and LAMB. Each of these algorithms offers unique benefits in convergence speed, stability, and resource efficiency:

Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD): This classic algorithm updates model weights based on mini-batches, which are small subsets of the full dataset. By doing so, SGD can perform faster updates and make the training process less computationally intensive compared to full-batch updates. However, SGD may converge slowly, especially on complex, high-dimensional problems like LLMs.

Adam (Adaptive Moment Estimation): Adam is a popular choice for training LLMs because it combines momentum and adaptive learning rates. Momentum helps smooth the optimization path by giving preference to previous gradients, while adaptive learning rates allow different parameters to have unique adjustment rates. This combination enables Adam to handle diverse data distributions effectively, making it robust for LLMs.

RMSprop: This algorithm adjusts learning rates based on recent gradient magnitudes. By adapting step sizes according to the variance of gradients, RMSprop is especially useful in models where gradient scales vary across different layers.

LAMB (Layer-wise Adaptive Moments for Batch Training): LAMB is designed for training large-batch models by scaling learning rates in proportion to layer norms, which helps maintain stability across layers. This makes it highly effective for training very large models, such as LLMs.

Efficient training requires minimizing the number of steps to reach acceptable accuracy levels, which is achieved through techniques like learning rate schedules, warm restarts, and adaptive learning rates:

Learning Rate Schedules: These adjust the learning rate over time, often using decay formulas like exponential decay. For instance, an exponential decay function $\eta_t = \eta_0 \times e^{-\lambda t}$ reduces the learning rate as training progresses, allowing for larger steps initially and finer adjustments near convergence. This approach helps models stabilize as they approach an optimal solution.

Warm Restarts: This technique periodically resets the learning rate, allowing the model to escape local minima and explore different regions of the solution space. By periodically increasing the learning rate, warm restarts can lead to improved convergence and better final accuracy.

Rust’s strong type safety and precise control over numeric types provide an ideal environment for implementing these techniques. Rust allows stable updates as parameters dynamically adjust, ensuring safety in matrix operations and minimizing runtime errors. In Rust, implementing optimization algorithms and convergence techniques involves leveraging crates like tch-rs and candle. Both libraries support efficient tensor operations and custom optimization routines, and they offer GPU acceleration when available. The tch-rs crate uses PyTorch's backend, making it highly compatible with pre-trained PyTorch models. The candle crate, on the other hand, provides a more Rust-centric approach, offering greater flexibility for implementing custom optimizers from scratch.

This code demonstrates the implementation of a simple feedforward neural network with two layers using the Rust programming language. The network is trained using synthetic data generated to match a basic regression task, where the model learns to approximate the sum of input features. To optimize the model’s weights, the Adam optimizer is applied, which combines momentum and adaptive learning rates to enhance convergence and stability during training. Rust’s ndarray library is used for handling matrix operations, and the neural network parameters are managed using Arc and Mutex to support concurrent access in multi-threaded environments. The model undergoes several epochs of training, and batch processing is used to improve efficiency by iteratively updating the model with small subsets of data.

use ndarray::{Array, Array2, Axis, s};

use ndarray_rand::rand_distr::Uniform;

use ndarray_rand::RandomExt;

use std::sync::{Arc, Mutex};

use std::time::Instant;

// Define hyperparameters

const INPUT_SIZE: usize = 10;

const HIDDEN_SIZE: usize = 64;

const OUTPUT_SIZE: usize = 1;

const LEARNING_RATE: f32 = 0.01;

const BATCH_SIZE: usize = 64;

const EPOCHS: usize = 10;

// Adam optimizer struct

struct Adam {

learning_rate: f32,

beta1: f32,

beta2: f32,

epsilon: f32,

t: usize,

m_w1: Array2<f32>,

v_w1: Array2<f32>,

m_b1: Array2<f32>,

v_b1: Array2<f32>,

m_w2: Array2<f32>,

v_w2: Array2<f32>,

m_b2: Array2<f32>,

v_b2: Array2<f32>,

}

impl Adam {

fn new(shape_w1: (usize, usize), shape_b1: (usize, usize), shape_w2: (usize, usize), shape_b2: (usize, usize), learning_rate: f32) -> Self {

Self {

learning_rate,

beta1: 0.9,

beta2: 0.999,

epsilon: 1e-8,

t: 0,

m_w1: Array2::zeros(shape_w1),

v_w1: Array2::zeros(shape_w1),

m_b1: Array2::zeros(shape_b1),

v_b1: Array2::zeros(shape_b1),

m_w2: Array2::zeros(shape_w2),

v_w2: Array2::zeros(shape_w2),

m_b2: Array2::zeros(shape_b2),

v_b2: Array2::zeros(shape_b2),

}

}

fn update_w2(&mut self, param: &mut Array2<f32>, grad: &Array2<f32>) {

self.t += 1;

self.m_w2 = self.beta1 * &self.m_w2 + (1.0 - self.beta1) * grad;

self.v_w2 = self.beta2 * &self.v_w2 + (1.0 - self.beta2) * grad.mapv(|x| x * x);

let m_hat = &self.m_w2 / (1.0 - self.beta1.powi(self.t as i32));

let v_hat = &self.v_w2 / (1.0 - self.beta2.powi(self.t as i32));

*param -= &(self.learning_rate * &m_hat / (v_hat.mapv(f32::sqrt) + self.epsilon));

}

fn update_b2(&mut self, param: &mut Array2<f32>, grad: &Array2<f32>) {

self.m_b2 = self.beta1 * &self.m_b2 + (1.0 - self.beta1) * grad;

self.v_b2 = self.beta2 * &self.v_b2 + (1.0 - self.beta2) * grad.mapv(|x| x * x);

let m_hat = &self.m_b2 / (1.0 - self.beta1.powi(self.t as i32));

let v_hat = &self.v_b2 / (1.0 - self.beta2.powi(self.t as i32));

*param -= &(self.learning_rate * &m_hat / (v_hat.mapv(f32::sqrt) + self.epsilon));

}

fn update_w1(&mut self, param: &mut Array2<f32>, grad: &Array2<f32>) {

self.m_w1 = self.beta1 * &self.m_w1 + (1.0 - self.beta1) * grad;

self.v_w1 = self.beta2 * &self.v_w1 + (1.0 - self.beta2) * grad.mapv(|x| x * x);

let m_hat = &self.m_w1 / (1.0 - self.beta1.powi(self.t as i32));

let v_hat = &self.v_w1 / (1.0 - self.beta2.powi(self.t as i32));

*param -= &(self.learning_rate * &m_hat / (v_hat.mapv(f32::sqrt) + self.epsilon));

}

fn update_b1(&mut self, param: &mut Array2<f32>, grad: &Array2<f32>) {

self.m_b1 = self.beta1 * &self.m_b1 + (1.0 - self.beta1) * grad;

self.v_b1 = self.beta2 * &self.v_b1 + (1.0 - self.beta2) * grad.mapv(|x| x * x);

let m_hat = &self.m_b1 / (1.0 - self.beta1.powi(self.t as i32));

let v_hat = &self.v_b1 / (1.0 - self.beta2.powi(self.t as i32));

*param -= &(self.learning_rate * &m_hat / (v_hat.mapv(f32::sqrt) + self.epsilon));

}

}

// Define neural network structure

struct NeuralNetwork {

w1: Arc<Mutex<Array2<f32>>>,

b1: Arc<Mutex<Array2<f32>>>,

w2: Arc<Mutex<Array2<f32>>>,

b2: Arc<Mutex<Array2<f32>>>,

}

impl NeuralNetwork {

fn new() -> Self {

let w1 = Array::random((INPUT_SIZE, HIDDEN_SIZE), Uniform::new(-0.5, 0.5));

let b1 = Array::zeros((1, HIDDEN_SIZE));

let w2 = Array::random((HIDDEN_SIZE, OUTPUT_SIZE), Uniform::new(-0.5, 0.5));

let b2 = Array::zeros((1, OUTPUT_SIZE));

NeuralNetwork {

w1: Arc::new(Mutex::new(w1)),

b1: Arc::new(Mutex::new(b1)),

w2: Arc::new(Mutex::new(w2)),

b2: Arc::new(Mutex::new(b2)),

}

}

fn forward_layer1(&self, x: &Array2<f32>) -> Array2<f32> {

let w1 = self.w1.lock().unwrap();

let b1 = self.b1.lock().unwrap();

(x.dot(&*w1) + &*b1).mapv(f32::tanh)

}

fn forward_layer2(&self, h1: &Array2<f32>) -> Array2<f32> {

let w2 = self.w2.lock().unwrap();

let b2 = self.b2.lock().unwrap();

h1.dot(&*w2) + &*b2

}

}

// Generate synthetic data

fn generate_synthetic_data(n: usize) -> (Array2<f32>, Array2<f32>) {

let x = Array::random((n, INPUT_SIZE), Uniform::new(0., 1.));

let y = x.sum_axis(Axis(1)).to_shape((n, OUTPUT_SIZE)).unwrap().to_owned();

(x, y)

}

// Train the model

fn train_model(nn: Arc<NeuralNetwork>, x: &Array2<f32>, y: &Array2<f32>, optimizer: &mut Adam) {

let h1 = nn.forward_layer1(x);

let output = nn.forward_layer2(&h1);

let error = &output - y;

let d_w2 = h1.t().dot(&error).to_owned();

let d_b2 = error.sum_axis(Axis(0)).to_shape((1, OUTPUT_SIZE)).unwrap().to_owned();

// Update layer 2 weights

{

let mut nn_w2 = nn.w2.lock().unwrap();

optimizer.update_w2(&mut nn_w2, &d_w2);

}

{

let mut nn_b2 = nn.b2.lock().unwrap();

optimizer.update_b2(&mut nn_b2, &d_b2);

}

// Calculate gradients for layer 1

let nn_w2 = nn.w2.lock().unwrap();

let d_hidden = error.dot(&nn_w2.t()).mapv(|x| 1. - x.powi(2));

let d_w1 = x.t().dot(&d_hidden).to_owned();

let d_b1 = d_hidden.sum_axis(Axis(0)).to_shape((1, HIDDEN_SIZE)).unwrap().to_owned();

// Update layer 1 weights

{

let mut nn_w1 = nn.w1.lock().unwrap();

optimizer.update_w1(&mut nn_w1, &d_w1);

}

{

let mut nn_b1 = nn.b1.lock().unwrap();

optimizer.update_b1(&mut nn_b1, &d_b1);

}

}

fn main() {

let (x, y) = generate_synthetic_data(1000);

let nn = Arc::new(NeuralNetwork::new());

let mut optimizer = Adam::new((INPUT_SIZE, HIDDEN_SIZE), (1, HIDDEN_SIZE), (HIDDEN_SIZE, OUTPUT_SIZE), (1, OUTPUT_SIZE), LEARNING_RATE);

let start = Instant::now();

for epoch in 0..EPOCHS {

for i in (0..x.len_of(Axis(0))).step_by(BATCH_SIZE) {

let end_idx = std::cmp::min(i + BATCH_SIZE, x.len_of(Axis(0)));

let x_batch = x.slice(s![i..end_idx, ..]).to_owned();

let y_batch = y.slice(s![i..end_idx, ..]).to_owned();

train_model(nn.clone(), &x_batch, &y_batch, &mut optimizer);

}

println!("Epoch {} completed", epoch + 1);

}

println!("Training completed in {:?}", start.elapsed());

}

The code defines separate update functions for each layer’s weights and biases within the Adam optimizer, resolving issues with Rust’s strict borrowing rules. Each epoch performs mini-batch training, updating the network’s parameters based on calculated gradients, which are stored and managed independently for each layer. After each forward pass, the gradients are computed for both layers, and the Adam optimizer updates the parameters using these gradients, along with stored moving averages. The code exemplifies the use of memory-safe concurrency in Rust while handling potentially complex data transformations, enabling efficient and safe updates across multiple threads. This approach highlights Rust’s concurrency capabilities for machine learning tasks, allowing for safe parameter updates without mutable borrow conflicts.

The candle crate provides a Rust-native interface to define custom optimization routines. In this scenario, we’re building a text generation pipeline using Rust with the candle library, incorporating a custom optimizer to update model parameters based on gradients. The goal is to generate text sequences given a prompt by applying a machine learning model (such as a transformer-based language model) and using an optimizer with an exponential decay learning rate. This setup is useful for fine-tuning models, allowing control over parameter adjustments to enhance text generation quality, and provides a scalable approach for model deployment and updates.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0"

serde_json = "1.0.132"

reqwest = { version = "0.12.8", features = ["blocking"] }

candle-transformers = "0.7.2"

candle-core = "0.7.2"

candle-nn = "0.7.2"

hf-hub = "0.3.2"

tokenizers = "0.19"

candle-examples = "0.7.2"

tracing-subscriber = "0.3.18"

tracing-chrome = "0.7.2"

use anyhow::{Error as E, Result};

use candle_core::{DType, Device, Tensor, utils, Var};

use candle_nn::VarBuilder;

use candle_transformers::models::based::Model;

use candle_transformers::generation::LogitsProcessor;

use candle_examples::token_output_stream::TokenOutputStream;

use hf_hub::{api::sync::Api, Repo, RepoType};

use tokenizers::Tokenizer;

use std::time::Instant;

use std::io::Write;

struct TextGeneration {

model: Model,

device: Device,

tokenizer: TokenOutputStream,

logits_processor: LogitsProcessor,

repeat_penalty: f32,

repeat_last_n: usize,

optimizer: CustomOptimizer,

}

impl TextGeneration {

#[allow(clippy::too_many_arguments)]

fn new(

model: Model,

tokenizer: Tokenizer,

seed: u64,

temp: Option<f64>,

top_p: Option<f64>,

repeat_penalty: f32,

repeat_last_n: usize,

device: &Device,

learning_rate: f64,

decay_rate: f64,

) -> Self {

let logits_processor = LogitsProcessor::new(seed, temp, top_p);

let optimizer = CustomOptimizer::new(learning_rate, decay_rate);

Self {

model,

tokenizer: TokenOutputStream::new(tokenizer),

logits_processor,

repeat_penalty,

repeat_last_n,

device: device.clone(),

optimizer,

}

}

fn run(&mut self, prompt: &str, sample_len: usize) -> Result<()> {

self.tokenizer.clear();

let mut tokens = self

.tokenizer

.tokenizer()

.encode(prompt, true)

.map_err(E::msg)?

.get_ids()

.to_vec();

for &t in tokens.iter() {

if let Some(t) = self.tokenizer.next_token(t)? {

print!("{t}");

}

}

std::io::stdout().flush()?;

let mut generated_tokens = 0usize;

let eos_token = match self.tokenizer.get_token("<|endoftext|>") {

Some(token) => token,

None => anyhow::bail!("cannot find the <|endoftext|> token"),

};

let start_gen = Instant::now();

for index in 0..sample_len {

let context_size = if index > 0 { 1 } else { tokens.len() };

let start_pos = tokens.len().saturating_sub(context_size);

let ctxt = &tokens[start_pos..];

let input = Tensor::new(ctxt, &self.device)?.unsqueeze(0)?;

let logits = self.model.forward(&input, start_pos)?;

let logits = logits.squeeze(0)?.squeeze(0)?.to_dtype(DType::F32)?;

let logits = if self.repeat_penalty == 1. {

logits

} else {

let start_at = tokens.len().saturating_sub(self.repeat_last_n);

candle_transformers::utils::apply_repeat_penalty(

&logits,

self.repeat_penalty,

&tokens[start_at..],

)?

};

let next_token = self.logits_processor.sample(&logits)?;

tokens.push(next_token);

generated_tokens += 1;

if next_token == eos_token {

break;

}

if let Some(t) = self.tokenizer.next_token(next_token)? {

print!("{t}");

std::io::stdout().flush()?;

}

}

let dt = start_gen.elapsed();

if let Some(rest) = self.tokenizer.decode_rest().map_err(E::msg)? {

print!("{rest}");

}

std::io::stdout().flush()?;

println!(

"\n{generated_tokens} tokens generated ({:.2} token/s)",

generated_tokens as f64 / dt.as_secs_f64(),

);

Ok(())

}

// Example method to apply optimizer for parameter update

fn update_parameters(&mut self, gradients: &[Tensor]) -> Result<()> {

// Placeholder: Replace `&mut []` with actual model parameters if accessible

self.optimizer.apply_gradients(&mut [], gradients)

}

}

struct CustomOptimizer {

learning_rate: f64,

decay_rate: f64,

step: usize,

}

impl CustomOptimizer {

fn new(learning_rate: f64, decay_rate: f64) -> Self {

Self {

learning_rate,

decay_rate,

step: 0,

}

}

fn apply_gradients(&mut self, vars: &mut [Var], gradients: &[Tensor]) -> Result<()> {

let current_lr = self.learning_rate * (self.decay_rate.powf(self.step as f64));

self.step += 1;

for (var, grad) in vars.iter_mut().zip(gradients) {

// Scale the gradient by the current learning rate.

let update = (grad * current_lr)?;

// Compute the new value by subtracting the update from the original tensor.

let updated_tensor = var.as_tensor().sub(&update)?;

// Reassign the variable to the updated tensor using `from_tensor`.

*var = Var::from_tensor(&updated_tensor)?;

}

Ok(())

}

}

fn main() -> Result<()> {

let tracing_enabled = true; // Enable or disable tracing.

let prompt = "Once upon a time"; // The prompt text for generation.

let temperature = Some(0.7); // Sampling temperature.

let top_p = Some(0.9); // Nucleus sampling probability cutoff.

let seed = 299792458; // Random seed for generation.

let sample_len = 100; // Number of tokens to generate.

let model_id = "hazyresearch/based-360m".to_string(); // Model ID to use.

let revision = "refs/pr/1".to_string(); // Model revision.

let repeat_penalty = 1.1; // Repeat penalty factor.

let repeat_last_n = 64; // Context size for repeat penalty.

let cpu = true; // Whether to use CPU or GPU.

use tracing_chrome::ChromeLayerBuilder;

use tracing_subscriber::prelude::*;

let _guard = if tracing_enabled {

let (chrome_layer, guard) = ChromeLayerBuilder::new().build();

tracing_subscriber::registry().with(chrome_layer).init();

Some(guard)

} else {

None

};

println!(

"avx: {}, neon: {}, simd128: {}, f16c: {}",

utils::with_avx(),

utils::with_neon(),

utils::with_simd128(),

utils::with_f16c()

);

let start = Instant::now();

let api = Api::new()?;

let repo = api.repo(Repo::with_revision(

model_id,

RepoType::Model,

revision,

));

let config_file = repo.get("config.json")?;

let filenames = vec![repo.get("model.safetensors")?];

let repo = api.model("openai-community/gpt2".to_string());

let tokenizer_file = repo.get("tokenizer.json")?;

println!("retrieved the files in {:?}", start.elapsed());

let tokenizer = Tokenizer::from_file(tokenizer_file).map_err(E::msg)?;

let start = Instant::now();

let config = serde_json::from_reader(std::fs::File::open(config_file)?)?;

let device = candle_examples::device(cpu)?;

let dtype = if device.is_cuda() {

DType::BF16

} else {

DType::F32

};

let vb = unsafe { VarBuilder::from_mmaped_safetensors(&filenames, dtype, &device)? };

let model = Model::new(&config, vb)?;

println!("loaded the model in {:?}", start.elapsed());

let mut pipeline = TextGeneration::new(

model,

tokenizer,

seed,

temperature,

top_p,

repeat_penalty,

repeat_last_n,

&device,

0.01, // Initial learning rate for optimizer

0.99, // Decay rate for learning rate

);

pipeline.run(&prompt, sample_len)?;

// Assuming you have computed gradients, apply optimizer update

let gradients = vec![]; // Placeholder for actual gradient tensors

pipeline.update_parameters(&gradients)?;

Ok(())

}

The code initializes a text generation system with a TextGeneration struct that holds the model, tokenizer, and a custom optimizer (CustomOptimizer). The optimizer applies gradient-based updates with an exponential decay learning rate to fine-tune model parameters. The run function in TextGeneration generates text based on a given prompt by encoding it into tokens, passing them through the model, and sampling generated tokens until reaching the desired sequence length. The custom optimizer (CustomOptimizer) manages parameter updates, and each gradient update is scaled by a decaying learning rate. The main function orchestrates model and device setup, retrieves model files, initializes the pipeline, and triggers text generation, demonstrating a full setup for text generation and fine-tuning in Rust.

Optimization algorithms impact training efficiency, particularly in balancing convergence speed with model stability. For instance, while SGD offers simplicity and low computational overhead, it often requires additional techniques like momentum or adaptive learning rates to achieve stable convergence in complex LLMs. Regularization techniques, such as L2 regularization and dropout, are crucial in maintaining efficient training by preventing overfitting. L2 regularization, defined as $\frac{\lambda}{2} \sum \theta^2$, penalizes large weights, promoting smoother model parameters and reducing the risk of overfitting. Dropout randomly deactivates neurons during training, which helps generalize the model by exposing it to varied representations. Rust’s type safety and memory management allow for efficient implementation of these regularization methods, enhancing model robustness without overextending computational resources.

Advanced optimization techniques, including gradient clipping and weight decay, further improve training outcomes by controlling parameter updates. Gradient clipping prevents exploding gradients by capping the gradient magnitude at a predefined threshold ccc, ensuring that parameter updates remain within a manageable range. This technique is especially important in recurrent architectures or deep networks, where gradients can grow excessively large. Weight decay, similar to L2 regularization, applies a constant decay rate to weights, preventing excessive growth and promoting model stability. Rust’s precision control ensures accurate implementation of these techniques, providing a stable foundation for efficient and effective training.

Experimenting with various learning rate schedules and adaptive learning rates in Rust can reveal optimal configurations for fast and stable convergence. For example, cosine annealing adjusts the learning rate according to a cosine function, allowing smooth transitions between high and low rates, defined as: