Chapter 7

‘Multitask Learning: T5 and Unified Models’

"Multitask learning is a powerful paradigm that leverages shared representations to enable models to perform well across a variety of tasks, often surpassing the performance of task-specific models." — Andrew Ng

Chapter 7 of LMVR delves into the realm of multitask learning, highlighting the architecture and capabilities of models like T5 and other unified models. The chapter begins by explaining the fundamentals of multitask learning and its advantages over single-task approaches, emphasizing the importance of shared representations across tasks. It then explores the T5 architecture, which frames every NLP problem as a text-to-text task, providing a unified approach to solving diverse tasks within a single model. The chapter also covers the challenges and strategies for fine-tuning these models for specific applications, the methods for evaluating multitask models across different tasks, and the techniques for scaling and optimizing these models for real-world deployment. Finally, it looks ahead to the future of multitask learning, discussing trends such as multimodal learning and continual learning, and their implications for the evolution of AI.

7.1. Introduction to Multitask Learning

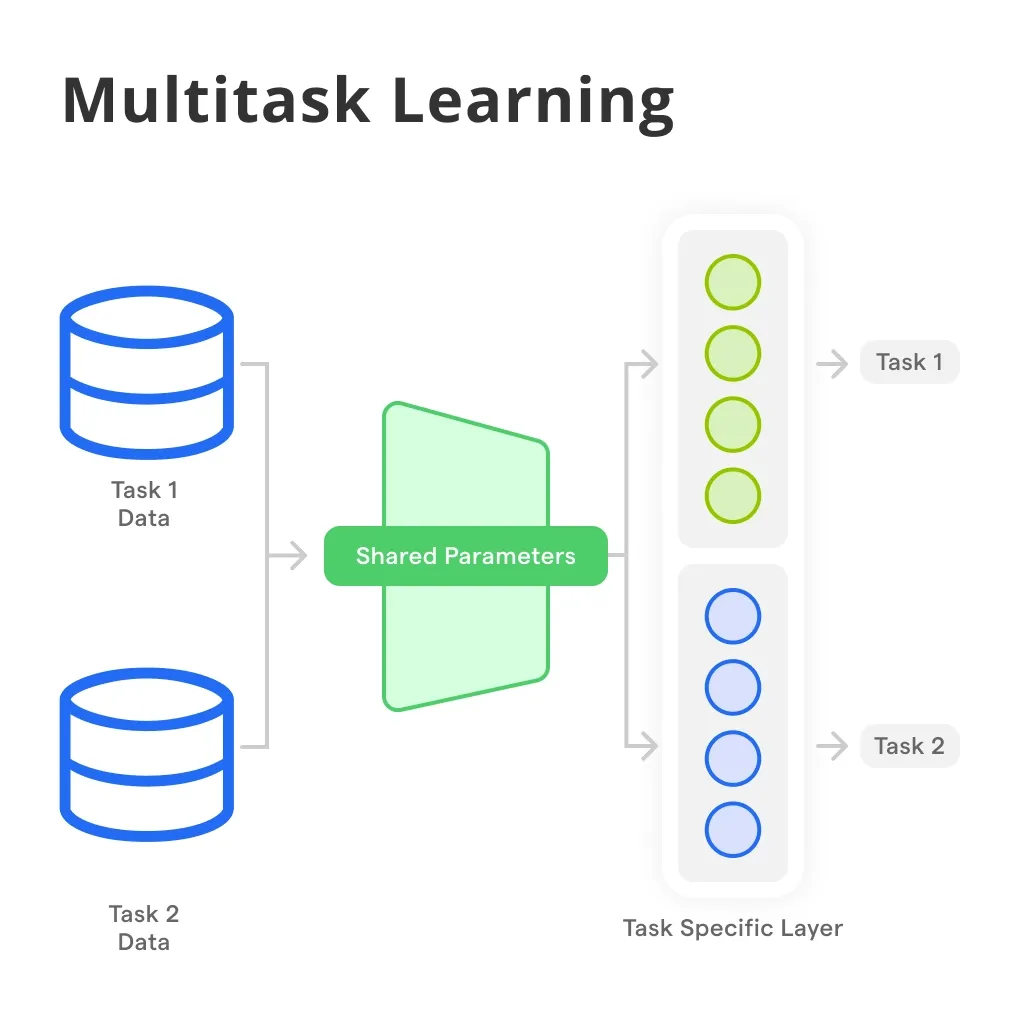

Multitask learning (MTL) is an approach in machine learning where a model is trained to perform multiple tasks simultaneously, leveraging shared representations across tasks to improve generalization and efficiency. Unlike single-task learning, where a model is trained on a specific task in isolation, multitask learning aims to improve performance by capturing underlying patterns that are useful across different tasks. The key idea is that tasks can share knowledge and representations, allowing the model to generalize better and avoid overfitting to individual tasks by using data from all tasks to refine its understanding.

In multitask learning, consider the example of sentiment analysis and topic classification, where a model is trained on customer reviews for sentiment analysis (positive, negative, neutral) and on news articles for topic classification (such as politics, sports, and technology). By sharing parameters in the initial text processing layers, the model learns general language patterns that benefit both tasks. Sentiment analysis can gain from topic context, as sentiments often vary across topics, while topic classification improves by understanding sentiment-associated language features. Similarly, in a computer vision example, training a model on image classification (where each image has one label, like "cat" or "dog") and object detection (identifying multiple objects, like detecting both "cat" and "dog" in the same image) allows shared convolutional layers to capture features like edges and shapes, which help with both identifying single objects and detecting multiple ones within images. Another example could involve predicting housing prices and crime rates, where neighborhood features such as income levels, proximity to schools, and local amenities impact both outcomes. Sharing parameters in the initial layers enables the model to learn neighborhood characteristics that improve predictions for both housing prices and crime rates. In each example, shared parameters allow the model to capture patterns beneficial across tasks, preventing overfitting to any one task and enhancing generalization, which is the essence of multitask learning.

Figure 1: Illustration of Multitask Learning paradigm.

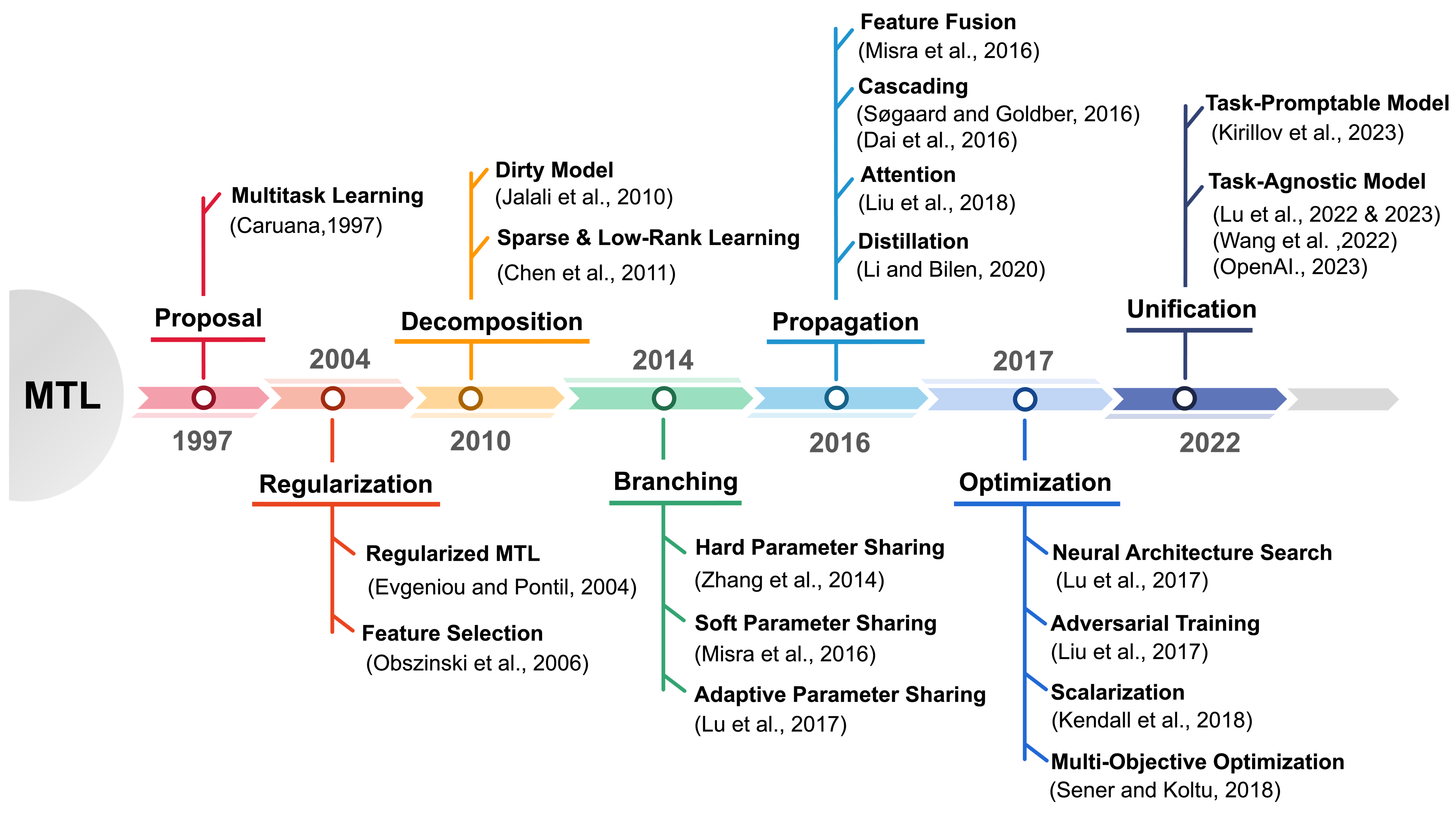

The concept of Multitask Learning (MTL) was first proposed by Rich Caruana in 1997 as an innovative approach to machine learning, where a single model is trained to perform multiple tasks concurrently by sharing representations across tasks. Caruana introduced MTL with the idea that sharing parameters among tasks allows a model to capture underlying structures common to these tasks, thereby improving generalization and helping prevent overfitting. Caruana’s work laid the foundation for MTL by demonstrating how learning multiple related tasks together could make each task more efficient by leveraging shared information, a significant departure from single-task learning.

Since Caruana's proposal, MTL has evolved through a series of advancements, particularly in the areas of regularization, decomposition, branching, propagation, optimization, and unification. In the early 2000s, researchers focused on developing better regularization techniques to control how shared representations influence individual tasks, enabling better balance between learning shared patterns and task-specific details. Decomposition techniques emerged, allowing the model to separate general and task-specific knowledge by selectively sharing parameters and effectively disentangling features that are only useful for particular tasks. Branching architectures further refined this by incorporating task-specific layers at later stages in the network, allowing different tasks to diverge in ways that improved performance on specialized subtasks while still using shared representations in the earlier layers.

Figure 2: Historical journey of Multitask Learning paradigm.

By the 2010s, propagation methods became integral to MTL, enabling more efficient ways to share information across tasks. Researchers explored techniques like cross-stitch networks and conditional computation, where only relevant features were shared between specific tasks, enhancing generalization by allowing knowledge to propagate selectively rather than uniformly across all tasks. Optimization strategies for MTL were also crucial in this period, particularly for designing gradient-based methods that could handle the complex interactions between tasks. Techniques such as task weighting were developed to adjust the learning emphasis on each task dynamically, ensuring that none dominated or hindered the progress of others.

Approaching 2022, MTL research turned towards unifying various approaches to develop flexible architectures capable of dynamically adapting to multiple tasks, even as task complexity and diversity increased. Unification involved blending different strategies, such as combining regularization, decomposition, and propagation techniques in a single model framework that could accommodate a variety of tasks with minimal fine-tuning. This era of MTL brought in frameworks that allowed a model to allocate resources based on task requirements dynamically, making MTL more robust and adaptable across various domains, from natural language processing to computer vision. These advancements have redefined MTL, building on Caruana’s vision by creating models that leverage shared information to improve both efficiency and adaptability in complex, multi-task environments

Mathematically, multitask learning can be framed as an optimization problem where the model minimizes a weighted combination of loss functions across multiple tasks. For a set of tasks $T_1, T_2, \dots, T_n$, with corresponding loss functions $\mathcal{L}_1, \mathcal{L}_2, \dots, \mathcal{L}_n$, the overall loss function in multitask learning can be expressed as:

$$ \mathcal{L}_{\text{MTL}} = \sum_{i=1}^{n} \lambda_i \mathcal{L}_i, $$

where $\lambda_i$ are the weights that control the relative importance of each task's loss. The model must balance minimizing these losses in a way that improves performance across all tasks, while also ensuring that no single task dominates the learning process. One of the primary advantages of multitask learning is that it allows the model to benefit from auxiliary tasks, which can provide additional data and regularization that help improve performance on the primary tasks of interest.

The difference between single-task learning and multitask learning lies in the structure of the model and how information is shared across tasks. In single-task learning, the model typically consists of task-specific layers that focus on learning representations tailored to the target task. In multitask learning, the model is divided into shared layers, which learn representations common across all tasks, and task-specific layers, which focus on learning features unique to each task. The shared layers enable the model to capture more generalizable features, reducing the risk of overfitting to any one task. However, the challenge lies in determining the right balance between shared and task-specific layers. Too much sharing can lead to task interference, where learning representations for one task negatively impacts the performance of others, while too little sharing limits the benefits of multitask learning.

One key application where multitask learning has shown significant success is in natural language understanding (NLU). Models like T5 (Text-To-Text Transfer Transformer) utilize multitask learning to handle a wide range of tasks, including translation, summarization, and question-answering, within a single framework. The shared representations learned by the model across these tasks allow it to transfer knowledge from one task to another, improving performance and data efficiency. For example, a multitask model trained on both translation and summarization may learn to represent sentence structures and semantic relations more effectively, which benefits both tasks.

Balancing shared and task-specific layers is critical in multitask learning. Shared layers are responsible for learning common features across tasks, while task-specific layers capture unique characteristics of individual tasks. This balance can be formalized by splitting the model into a shared backbone $f_{\text{shared}}(x)$ and task-specific heads $f_{\text{task}_i}(x)$. The shared backbone is trained using data from all tasks, while each task-specific head is optimized using data relevant to its specific task. This structure can be expressed as:

$$ y_i = f_{\text{task}_i}(f_{\text{shared}}(x)), $$

where $x$ represents the input, $f_{\text{shared}}$ represents the shared layers, and $f_{\text{task}_i}$ represents the task-specific layer for task $i$. The effectiveness of multitask learning depends on how well the shared layers generalize across tasks while the task-specific layers handle the nuances of each task. One benefit of this approach is that it reduces overfitting, as the model is less likely to memorize task-specific details when it is forced to learn general representations that apply across tasks.

In terms of data efficiency, multitask learning allows models to leverage data from multiple tasks, which is particularly useful in low-data regimes. Since the model can learn shared representations from all tasks, it can perform better on tasks with limited labeled data by transferring knowledge from related tasks with more abundant data. This cross-task data sharing helps improve the model's ability to generalize, especially when tasks are similar or complementary.

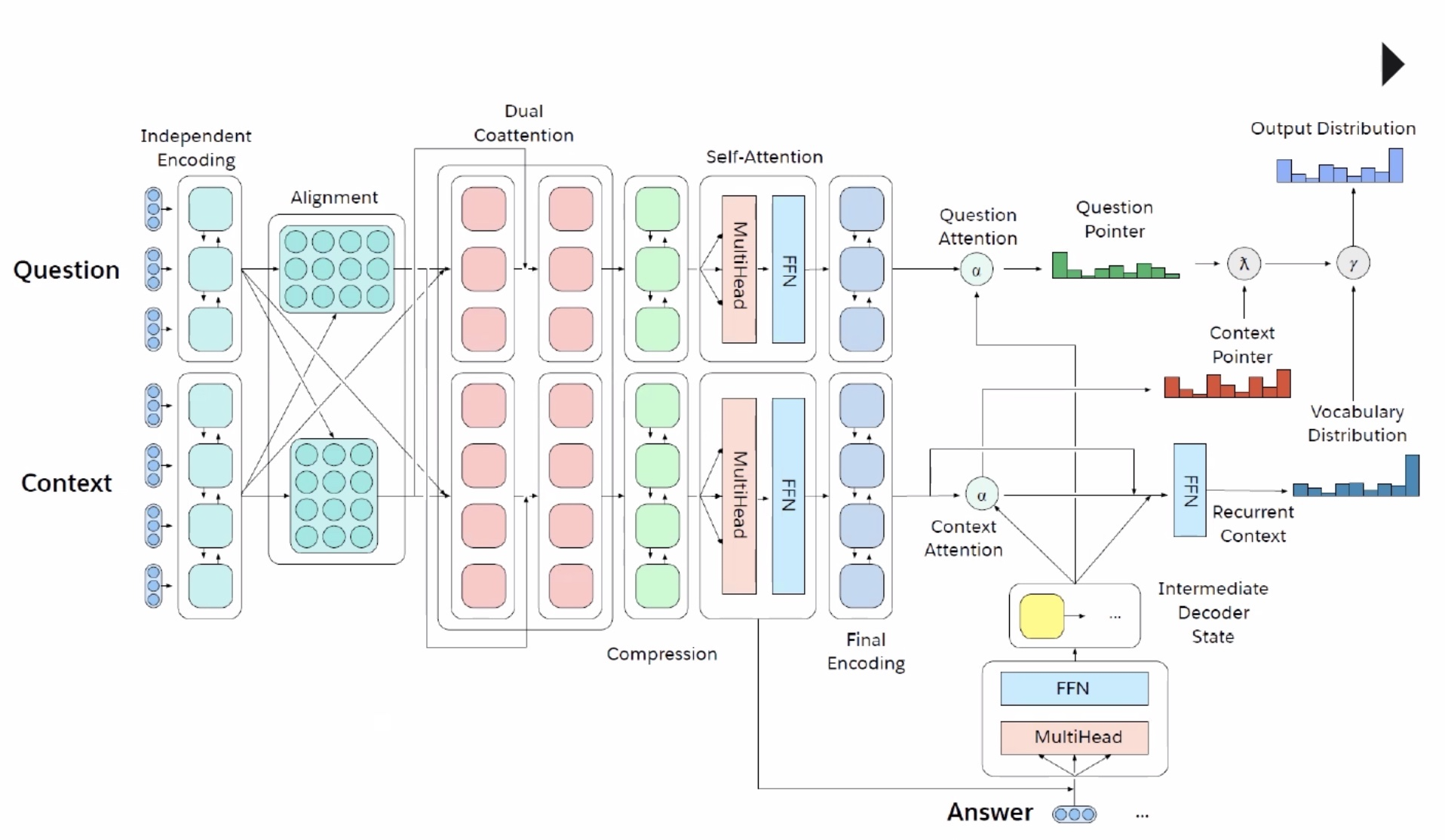

Figure 3: Illustration of context aware Q&A system.

In a multitask learning (MTL) architecture designed for Question Answering (Q&A) and Context Learning tasks, the model begins with independent encoding, where separate encoders process the question and context inputs for each task. This separation allows for initial feature extraction without immediate task interference, setting a strong foundation for shared learning. An alignment encoding layer then follows, aligning question and context representations to capture associations that link the two tasks, thereby preparing the inputs for the dual co-attention layer. In the dual co-attention layer, the model performs cross-attention between questions and contexts, allowing each task to focus on its relevant parts: Q&A narrows in on potential answer locations, while Context Learning emphasizes question-relevant areas to enhance its comprehension of the context. After co-attention, a self-attention layer further refines each task’s representations by capturing internal dependencies across the input sequence, helping the model gain a deeper understanding of long-range relationships. These refined outputs then pass through a final encoding layer, producing task-specific representations in question and context attentions. The question attention prioritizes answer spans in the context for Q&A, while context attention enables Context Learning to focus on structural and semantic comprehension. Finally, a Feed-Forward Network (FFN) and multi-head attention combine these attentions, enabling the model to generate precise answers for Q&A and well-contextualized responses for Context Learning. This structure effectively balances shared learning with task-specific focus, enabling both tasks to benefit from each other without diminishing individual performance.

Despite these advantages, multitask learning also faces challenges, especially in managing task interference, where optimizing for one task can conflict with the goals of another, leading to reduced performance. Task interference becomes particularly problematic when tasks are dissimilar or have conflicting objectives, as excessive parameter sharing or using identical representations can result in suboptimal learning for specific tasks. Balancing the loss functions across tasks, often termed loss balancing, is another critical challenge in MTL. Choosing the appropriate task loss weights ($\lambda_i$) is essential to prevent any one task from overshadowing the others. Techniques such as dynamic task weighting and uncertainty-based weighting have been introduced to address this challenge, enabling the model to adjust task weights adaptively throughout training and thereby optimize for multiple tasks without sacrificing the performance of individual tasks. Together, these architectural design choices and solutions to MTL’s challenges contribute to achieving a model that balances task interactions while maximizing overall efficiency and accuracy.

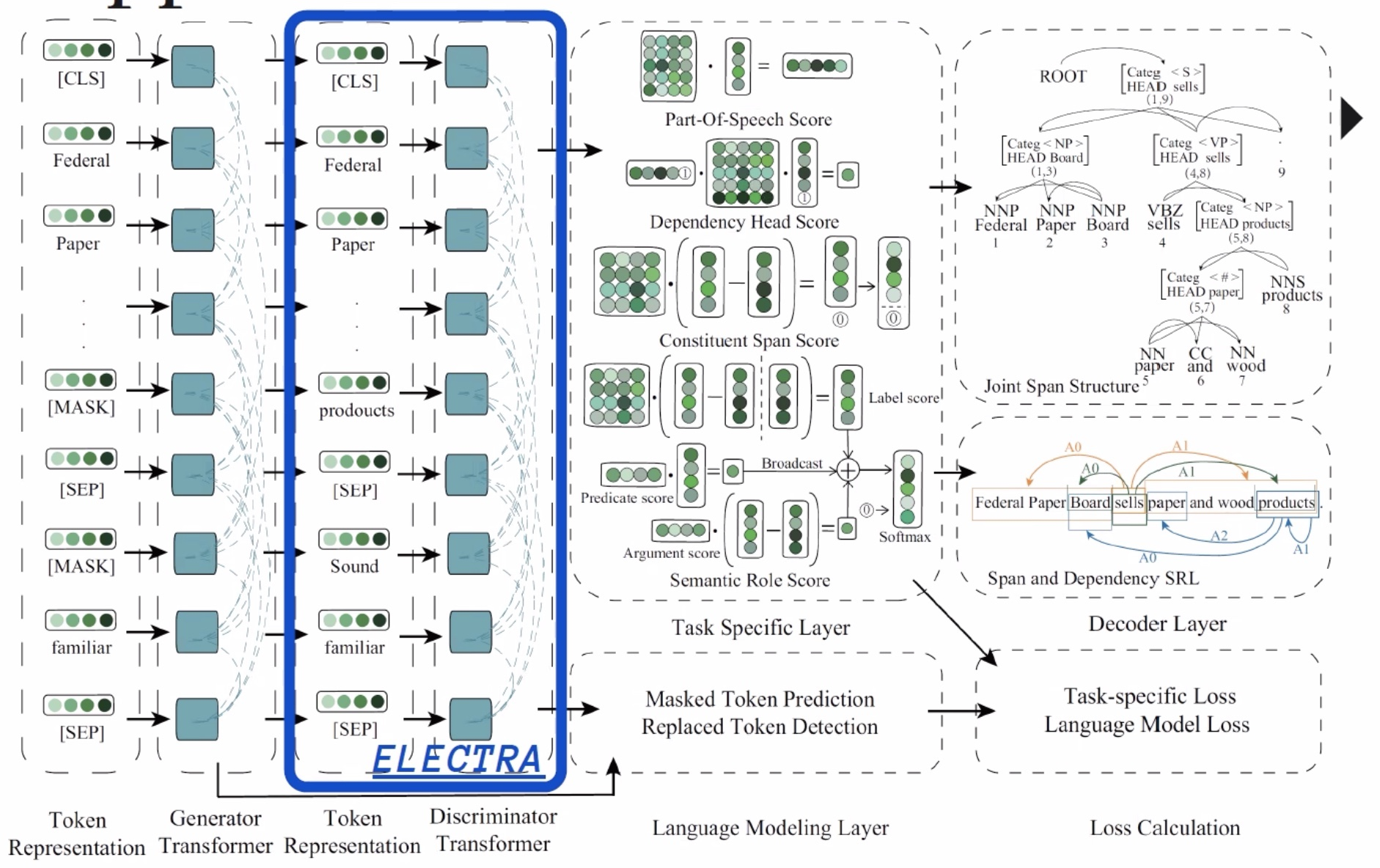

In a multitask learning (MTL) architecture inspired by models like ELECTRA, input token representations follow a dual processing path through a generator, a discriminator, and task-specific layers. This approach begins by encoding input tokens using embeddings that capture the semantic and syntactic properties of each token. These embeddings are then fed into the generator, which functions differently from traditional masked language models like BERT. Instead of predicting masked tokens, the generator in ELECTRA replaces certain tokens with plausible alternatives. The generator’s goal is to produce realistic, contextually appropriate replacements rather than just filling in masks, thereby enhancing the model’s understanding of context and token semantics.

Figure 4: Example of ELECTRA-based MTL model architecture.

Following the generator, the processed tokens are passed through a discriminator, whose role is to identify whether each token in the input sequence is a genuine (real) token or one that was replaced by the generator. The discriminator doesn’t reprocess the embeddings sequentially but rather evaluates the likelihood of each token being "real" or "fake," based on the context. This step teaches the model to recognize context-sensitive token replacements, effectively training it to discern nuanced contextual relationships. This distinction allows ELECTRA to capture generalizable language patterns that can benefit multiple tasks.

Once tokens are processed by the discriminator, the resulting representations can be passed to task-specific language model layers tailored for various linguistic tasks, such as Part-of-Speech (POS) scoring, which assigns syntactic tags (e.g., noun, verb) to each token; Dependency Head scoring, which identifies the syntactic head for each word to clarify relationships between tokens; Constituent Span scoring, defining phrase boundaries like noun or verb phrases; and Semantic Role scoring, which assigns functional roles within sentences, such as identifying agents, patients, or instruments. Each of these tasks utilizes a final Feed-Forward Network (FFN), typically followed by task-specific softmax or scoring layers, to transform embeddings into the desired outputs, such as POS tags or dependency heads.

ELECTRA-based MTL models are highly efficient in performing multiple linguistic tasks simultaneously because each task leverages the shared representations from both generator and discriminator layers. This structure allows the model to capture broad, general language patterns in early layers and then specialize representations for specific linguistic tasks in later layers. By leveraging the unique generator-discriminator setup, this architecture achieves strong performance across diverse tasks without needing separate models for each, enhancing both efficiency and accuracy across a range of language processing tasks.

In term of practical implementation, the rust-bert library provides Rust bindings to various pretrained Transformer models, enabling developers to perform advanced natural language processing tasks like summarization, translation, text generation, and question answering. In this example, we use the rust-bert library to load a small T5 model for text summarization. The T5 model is highly adaptable and performs well on summarization tasks, making it a good choice for applications that need concise summaries of longer texts. Using the pretrained T5 model, this code demonstrates how rust-bert can be configured and used in Rust, offering an efficient, Rust-native interface to interact with cutting-edge NLP models.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0.90"

rust-bert = "0.19.0"

use anyhow::Result;

use rust_bert::pipelines::summarization::{SummarizationConfig, SummarizationModel};

use rust_bert::resources::RemoteResource;

use rust_bert::t5::{T5ConfigResources, T5ModelResources, T5VocabResources};

fn main() -> Result<()> {

// Define the resources needed for the summarization model

let config_resource = Box::new(RemoteResource::from_pretrained(T5ConfigResources::T5_SMALL));

let vocab_resource = Box::new(RemoteResource::from_pretrained(T5VocabResources::T5_SMALL));

let weights_resource = Box::new(RemoteResource::from_pretrained(T5ModelResources::T5_SMALL));

// Provide a dummy merges resource as required by the struct

let dummy_merges_resource = Box::new(RemoteResource::new("https://example.com", "dummy"));

// Set up the summarization model configuration

let summarization_config = SummarizationConfig {

model_type: rust_bert::pipelines::common::ModelType::T5,

model_resource: weights_resource,

config_resource,

vocab_resource,

merges_resource: dummy_merges_resource, // Using dummy resource here

min_length: 10,

max_length: 512,

..Default::default()

};

// Initialize the summarization model

let summarization_model = SummarizationModel::new(summarization_config)?;

// Input text for summarization

let input = ["In findings published Tuesday in Cornell University's arXiv by a team of scientists \

from the University of Montreal and a separate report published Wednesday in Nature Astronomy by a team \

from University College London (UCL), the presence of water vapour was confirmed in the atmosphere of K2-18b, \

a planet circling a star in the constellation Leo. This is the first such discovery in a planet in its star's \

habitable zone — not too hot and not too cold for liquid water to exist. The Montreal team, led by Björn Benneke, \

used data from the NASA's Hubble telescope to assess changes in the light coming from K2-18b's star as the planet \

passed between it and Earth. They found that certain wavelengths of light, which are usually absorbed by water, \

weakened when the planet was in the way, indicating not only does K2-18b have an atmosphere, but the atmosphere \

contains water in vapour form. The team from UCL then analyzed the Montreal team's data using their own software \

and confirmed their conclusion. This was not the first time scientists have found signs of water on an exoplanet, \

but previous discoveries were made on planets with high temperatures or other pronounced differences from Earth. \

\"This is the first potentially habitable planet where the temperature is right and where we now know there is water,\" \

said UCL astronomer Angelos Tsiaras. \"It's the best candidate for habitability right now.\" \"It's a good sign\", \

said Ryan Cloutier of the Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, who was not one of either study's authors. \

\"Overall,\" he continued, \"the presence of water in its atmosphere certainly improves the prospect of K2-18b being \

a potentially habitable planet, but further observations will be required to say for sure. \" \

K2-18b was first identified in 2015 by the Kepler space telescope. It is about 110 light-years from Earth and larger \

but less dense. Its star, a red dwarf, is cooler than the Sun, but the planet's orbit is much closer, such that a year \

on K2-18b lasts 33 Earth days. According to The Guardian, astronomers were optimistic that NASA's James Webb space \

telescope — scheduled for launch in 2021 — and the European Space Agency's 2028 ARIEL program, could reveal more \

about exoplanets like K2-18b."];

// Summarize the input text

let output = summarization_model.summarize(&input);

for sentence in output {

println!("{sentence}");

}

Ok(())

}

The code first configures and loads the T5 model with specific resources for configuration, vocabulary, and weights. These resources are downloaded from Hugging Face's Model Hub using RemoteResource. Since T5 does not require merges (typically used for BPE tokenization in models like GPT), a dummy resource is provided to fulfill the struct's requirements. Once the model is set up, the code inputs a sample article about the discovery of water vapor in the atmosphere of exoplanet K2-18b and uses the model's summarize function to generate a concise summary. Finally, the output is printed, showcasing how Rust can efficiently handle complex NLP tasks by leveraging pretrained models through rust-bert. This approach streamlines access to NLP tools in Rust and facilitates tasks requiring state-of-the-art language models in a production-ready environment.

Let see other practical example from the following code that demonstrates the setup and use of a pre-trained T5 language model for multilingual translation tasks using the rust-bert library, which provides high-level abstractions for working with state-of-the-art NLP models in Rust. This example showcases how organizations can leverage T5 for real-time translations across multiple languages by utilizing pre-trained models available through Hugging Face’s model hub. Such multilingual capabilities are valuable in applications requiring efficient and accurate translation of content for international audiences, such as global customer support systems, real-time language interpretation, and cross-lingual content generation.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0.90"

rust-bert = "0.19.0"

tch = "0.8.0"

use anyhow;

use rust_bert::pipelines::common::ModelType;

use rust_bert::pipelines::translation::{Language, TranslationConfig, TranslationModel};

use rust_bert::resources::RemoteResource;

use rust_bert::t5::{T5ConfigResources, T5ModelResources, T5VocabResources};

use tch::Device;

fn main() -> anyhow::Result<()> {

// Define resources for model configuration, vocabulary, and weights

let model_resource = RemoteResource::from_pretrained(T5ModelResources::T5_BASE);

let config_resource = RemoteResource::from_pretrained(T5ConfigResources::T5_BASE);

let vocab_resource = RemoteResource::from_pretrained(T5VocabResources::T5_BASE);

// Placeholder resource for merges (not needed for T5 but required by the API)

let merges_resource = RemoteResource::from_pretrained(T5VocabResources::T5_BASE);

// Define source and target languages for translation

let source_languages = vec![

Language::English,

Language::French,

Language::German,

Language::Indonesian,

];

let target_languages = vec![

Language::English,

Language::French,

Language::German,

Language::Indonesian,

];

// Configure translation model

let translation_config = TranslationConfig::new(

ModelType::T5,

model_resource.into(),

config_resource,

vocab_resource,

merges_resource, // Placeholder resource, not actively used

source_languages,

target_languages,

Device::cuda_if_available(),

);

// Initialize the model

let model = TranslationModel::new(translation_config)?;

// Define a source sentence for translation

let source_sentence = "This sentence will be translated into multiple languages.";

// Translate the sentence into multiple languages

let mut outputs = Vec::new();

outputs.push(model.translate(&[source_sentence], Language::English, Language::French)?);

outputs.push(model.translate(&[source_sentence], Language::English, Language::German)?);

outputs.push(model.translate(&[source_sentence], Language::English, Language::Indonesian)?);

// Print out the translated sentences

for output in outputs {

for sentence in output {

println!("{sentence}");

}

}

Ok(())

}

In the code, essential resources for the T5 model—including configuration, vocabulary, and model weights—are loaded from remote resources. Since the T5 model doesn't require a merges resource (used typically for certain tokenizers), a placeholder is provided to satisfy the library's API requirements. The translation configuration is set to work with English, French, German, and Romanian as both source and target languages. The code initializes a TranslationModel with this configuration and then translates a sample sentence from English to French, German, and Romanian. The translated sentences are then printed out, demonstrating the T5 model’s ability to handle various translation tasks seamlessly within a Rust application.

The T5 model family on [Hugging Face ](https://huggingface.co/docs/transformers/index)offers a range of variants tailored to meet different needs, from efficiency to performance, across diverse NLP tasks. The original T5 model comes in multiple sizes, each designed to fit specific computational requirements. These include t5-small, with 60 million parameters, suitable for lightweight applications, and t5-base, which has 220 million parameters and is optimal for moderately demanding tasks. Larger versions like t5-large (770 million parameters) and t5-3b (3 billion parameters) cater to more intensive tasks, while t5-11b, with 11 billion parameters, is the largest model, ideal for high-capacity NLP applications where accuracy is prioritized over computational efficiency.

The Flan-T5 series introduces an instruction-tuned approach to T5, allowing it to better understand and follow specific instructions, making it especially useful in tasks requiring guided responses, such as question-answering and summarization. The Flan-T5 models come in various sizes: flan-t5-small, flan-t5-base, flan-t5-large, flan-t5-xl, and flan-t5-xxl, each correlating with the parameter count and capacities of the original T5 variants. Flan-T5's tuning with additional instruction-based data makes it more adaptable for interactive applications where nuanced understanding of instructions improves user experience.

The T5 v1.1 models represent an improved version of the original T5 models, refined with architectural optimizations. Available in t5-v1_1-small, t5-v1_1-base, t5-v1_1-large, t5-v1_1-xl, and t5-v1_1-xxl, these models incorporate better training strategies and adjustments, resulting in more efficient performance with lower computational demands. T5 v1.1 is known for providing higher quality results with reduced resource requirements, making it an attractive choice for applications where cost-efficiency and quality need to be balanced.

MT5, the multilingual version of T5, addresses the needs of applications requiring support across languages. With models like mt5-small, mt5-base, mt5-large, mt5-xl, and mt5-xxl, MT5 serves multilingual tasks effectively, offering flexibility for developers needing translation, multilingual understanding, and generation capabilities. MT5’s architecture is optimized for multilingual NLP, making it well-suited for global applications, including translation services, cross-lingual search, and chatbots supporting diverse languages.

Lastly, the mT0 models, based on T5 and developed by BigScience, are instruction-tuned for multilingual tasks. These include mt0-small, mt0-base, mt0-large, mt0-xl, and mt0-xxl. mT0 is specifically designed to handle multilingual prompts and responses, offering benefits similar to Flan-T5 but optimized for diverse languages. These models excel in international NLP applications where understanding instructions in multiple languages is critical, such as in cross-lingual customer support and automated question-answering for global users.

Together, these T5 variants allow for versatility in NLP, from lightweight models for mobile and edge devices to large-scale models for high-performance tasks, enabling developers to select the best-suited model based on task complexity, language requirements, and computational constraints. The hf-hub crate in Rust makes it easy to integrate these Hugging Face T5 models directly into Rust applications by accessing Hugging Face’s extensive model hub. Using hf-hub, developers can fetch, download, and manage model resources from the Hugging Face Hub, streamlining the deployment of T5 models and other transformers in Rust projects. This capability enables Rust developers to efficiently leverage T5’s powerful NLP functions, such as summarization, translation, and question-answering, while also benefiting from the range of model sizes and multilingual support. By supporting seamless access to pretrained models, the hf-hub crate provides a flexible and scalable approach for incorporating state-of-the-art NLP directly into Rust applications.

Here's an example of how to use the hf-hub crate to download several T5 model variants from Hugging Face. This code will download the model files for t5-small, t5-base, and t5-large. The hf-hub crate provides an API for accessing models, datasets, and other resources hosted on the Hugging Face Hub, making it convenient to download and use models directly in Rust applications.

To run this example, ensure you have the hf-hub crate installed in your Cargo.toml:

[dependencies]

hf-hub = "0.9.0" # Check for the latest version on crates.io

anyhow = "1.0"

use anyhow;

use hf_hub::api::sync::Api;

use std::fs;

use std::path::Path;

fn main() -> anyhow::Result<()> {

let api = Api::new()?;

// List of T5 model variants to download

let models = ["t5-small", "t5-base", "t5-large"];

for &model in &models {

// Create model directory if it doesn't exist

let model_dir = Path::new("models").join(model);

fs::create_dir_all(&model_dir)?;

// Download config.json

let config_path = api.model(model.to_string()).get("config.json")?;

fs::copy(config_path, model_dir.join("config.json"))?;

// Download spiece.model (instead of vocab.json)

let spiece_path = api.model(model.to_string()).get("spiece.model")?;

fs::copy(spiece_path, model_dir.join("spiece.model"))?;

// Download pytorch_model.bin

let weights_path = api.model(model.to_string()).get("pytorch_model.bin")?;

fs::copy(weights_path, model_dir.join("pytorch_model.bin"))?;

println!("Downloaded {} model files to {:?}", model, model_dir);

}

Ok(())

}

This Rust code uses the hf-hub crate to download various T5 model variants from Hugging Face, specifically t5-small, t5-base, and t5-large, for use in NLP applications. The Api::new() function initializes a Hugging Face API client, enabling access to model repositories on the Hub. The code then defines a vector of model names and iterates over each one, specifying the repository and downloading essential files like config.json, vocab.json, and pytorch_model.bin for each model variant. These files are necessary for configuring, tokenizing, and loading the model's weights in downstream tasks. Each file is saved in a dedicated models directory with a unique name that corresponds to the specific model variant. By organizing the models in this way, the code enables efficient management and loading of T5 models for various NLP use cases in Rust, demonstrating how to leverage the Hugging Face Hub directly from Rust applications.

Recent trends in multitask learning focus on reducing task interference and enhancing scalability. Unified models, such as T5 and mT5, represent the forefront of multitask learning, designed to handle a wide range of tasks across multiple languages and modalities. These models use sophisticated architectures that balance shared and task-specific representations, often employing adaptive attention mechanisms to allocate resources dynamically based on task demands. Moreover, integrating multitask learning with large-scale pre-training and fine-tuning frameworks has become the predominant approach in NLP, enabling models to generalize more effectively across tasks and domains.

In industry, multitask learning is widely applied in scenarios requiring simultaneous handling of multiple related tasks within a unified framework. For instance, in customer service automation, a multitask model can handle varied requests such as answering FAQs, processing transactions, and providing product recommendations. By sharing knowledge across these tasks, the model improves performance on each task individually while streamlining training and deployment efficiency.

Benchmarking the effectiveness of multitask learning requires performance comparison against single-task models. This involves training single-task models independently on each task and evaluating them with standard metrics such as accuracy, BLEU score, or ROUGE score, depending on the specific task. The multitask model should demonstrate improvements from knowledge transfer between tasks and exhibit better data efficiency when trained on smaller datasets.

In conclusion, multitask learning enhances model generalization and data efficiency by leveraging shared representations across tasks. While it introduces challenges such as task interference and balancing of losses, multitask learning has proven effective in numerous real-world applications, particularly in NLP. Implementing multitask learning models in Rust presents an opportunity to explore these techniques in a high-performance, memory-efficient environment, allowing developers to optimize and deploy models capable of handling multiple tasks concurrently. As the field progresses, advancements in architectures and dynamic task management will further improve the scalability and efficacy of multitask learning systems.

7.2. The T5 Architecture

The T5 architecture represents a significant innovation in the realm of multitask learning for natural language processing (NLP). Developed by Google, T5 was designed as a unified model that frames every NLP task—from translation to summarization and question answering—within the same text-to-text format. This approach simplifies the model architecture and training process, as it treats both inputs and outputs as strings of text, regardless of the task. By using this standardized format, T5 allows for consistent learning across a wide range of NLP tasks, leveraging a shared architecture that adapts to various challenges without requiring task-specific modifications.

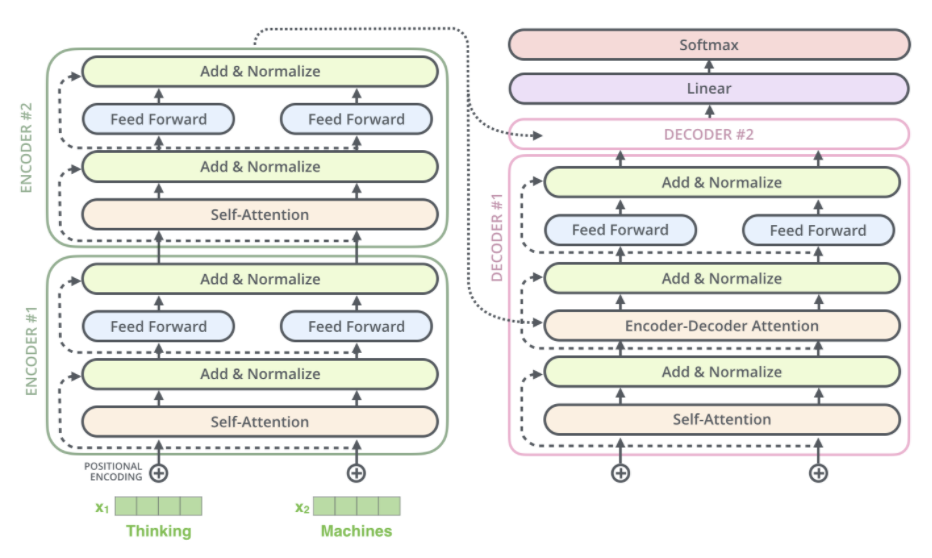

Figure 5: Illustration of T5’s encoder-decoder model architecture.

At its core, the T5 architecture is based on the Transformer model’s encoder-decoder structure. The input text is first passed through the encoder, which generates a contextualized representation of the input sequence. This representation is then fed into the decoder, which generates the output text token by token. The key innovation of T5 lies in how it reformulates every task into this text-to-text paradigm. For example, a translation task might take the input "translate English to French: What is your name?" and expect the output "Quel est votre nom?", while a summarization task would take an article as input and return its summary as output. Mathematically, this can be represented as a mapping from the input text $X$ to the output text $Y$, where the model learns the conditional probability distribution:

$$ P(Y | X) = \prod_{t=1}^{T} P(y_t | y_1, y_2, \dots, y_{t-1}, X), $$

where $y_t$ represents the token generated at each step, conditioned on both the input text $X$ and the previously generated tokens $y_1, y_2, \dots, y_{t-1}$. This formulation allows T5 to handle various tasks within the same framework, making it highly versatile.

One of the key advantages of the T5 model is its text-to-text format, which simplifies task definitions. In traditional multitask learning models, different tasks often require distinct architectures or output heads. However, T5 eliminates this need by using a single sequence-to-sequence architecture for all tasks, making it easier to train and fine-tune the model across a diverse set of tasks. The model’s ability to represent everything in the same format enhances its generalization capabilities, as the shared encoder-decoder layers can learn patterns that transfer well across tasks. This design also facilitates large-scale pre-training on massive datasets, enabling the model to acquire a broad understanding of language before fine-tuning on task-specific data.

Pre-training plays a critical role in the success of T5. During pre-training, the model is exposed to vast amounts of text data, where it learns to predict masked tokens in a text sequence, a task known as “span corruption.” This pre-training objective helps the model capture the underlying structure and relationships in language, making it highly effective when transferred to downstream tasks like translation or summarization. Pre-training in T5 is crucial for achieving high performance, as it provides the model with a strong foundation that can be fine-tuned for specific tasks with relatively little labeled data. The pre-training loss function can be expressed as:

$$ \mathcal{L}_{\text{pretrain}} = - \sum_{i=1}^{N} \log P(y_i | X_{\setminus i}), $$

where $y_i$ represents the masked tokens, and $X_{\setminus i}$ denotes the input sequence with certain spans masked out. This pre-training step ensures that T5 learns robust representations that can be efficiently adapted to a variety of NLP tasks.

T5’s ability to handle diverse tasks is a result of its flexible architecture and shared representation learning. By framing every task as a sequence-to-sequence problem, T5 ensures that the same model can be used for tasks as different as question answering and sentiment analysis. The encoder-decoder structure allows the model to generalize across tasks by learning common features in the input text while still generating task-specific outputs. This flexibility contrasts with other models that might require separate fine-tuning heads for each task, making T5 particularly efficient in multitask settings.

Scaling T5 has shown a significant impact on its performance across tasks. The original T5 model was released in various sizes, from small models with tens of millions of parameters to the largest models with billions of parameters. Empirical results have demonstrated that scaling up the number of parameters improves performance on almost every NLP task. This trend aligns with the general observation in deep learning that larger models, when properly trained, tend to generalize better and achieve superior results. However, scaling also introduces challenges related to computational resources, training time, and inference latency, which need to be carefully managed in real-world applications.

In Rust, implementing the T5 model involves defining its encoder-decoder architecture using frameworks like tch-rs, which provides Rust bindings to PyTorch. The encoder consists of a series of self-attention layers, where each token in the input attends to all other tokens to learn contextual representations. The decoder, also composed of self-attention layers, generates the output sequence based on the encoded representation and the tokens generated so far. This encoder-decoder framework is shared across all tasks, making the implementation of T5 in Rust straightforward for multitask learning.

use tch::{nn, nn::Module, nn::OptimizerConfig, Device, Tensor};

/// Define a basic T5 Encoder Block with self-attention and feed-forward layers

fn encoder_block(p: &nn::Path, n_embd: i64, n_heads: i64) -> impl Module {

let self_attn = nn::multi_head_attention(p / "self_attn", n_embd, n_heads);

let layer_norm1 = nn::layer_norm(p / "layer_norm1", vec![n_embd], Default::default());

let feed_forward = nn::seq()

.add(nn::linear(p / "lin1", n_embd, 4 * n_embd, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(p / "lin2", 4 * n_embd, n_embd, Default::default()));

let layer_norm2 = nn::layer_norm(p / "layer_norm2", vec![n_embd], Default::default());

nn::func(move |xs| {

let attn_output = xs.apply(&self_attn);

let x = xs + attn_output;

let x = x.apply(&layer_norm1);

let ff_output = x.apply(&feed_forward);

x + ff_output.apply(&layer_norm2)

})

}

/// Define the T5 Encoder

fn encoder(p: &nn::Path, n_embd: i64, n_layers: i64, n_heads: i64) -> impl Module {

let embedding = nn::embedding(p / "embedding", 32000, n_embd, Default::default());

let encoder_blocks: Vec<_> = (0..n_layers)

.map(|i| encoder_block(&p / format!("block_{}", i), n_embd, n_heads))

.collect();

nn::func(move |xs| {

let mut x = xs.apply(&embedding);

for block in &encoder_blocks {

x = x.apply(block);

}

x

})

}

/// Define a T5 Decoder Block with self-attention, encoder-decoder attention, and feed-forward layers

fn decoder_block(p: &nn::Path, n_embd: i64, n_heads: i64) -> impl Module {

let self_attn = nn::multi_head_attention(p / "self_attn", n_embd, n_heads);

let enc_dec_attn = nn::multi_head_attention(p / "enc_dec_attn", n_embd, n_heads);

let layer_norm1 = nn::layer_norm(p / "layer_norm1", vec![n_embd], Default::default());

let layer_norm2 = nn::layer_norm(p / "layer_norm2", vec![n_embd], Default::default());

let layer_norm3 = nn::layer_norm(p / "layer_norm3", vec![n_embd], Default::default());

let feed_forward = nn::seq()

.add(nn::linear(p / "lin1", n_embd, 4 * n_embd, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(p / "lin2", 4 * n_embd, n_embd, Default::default()));

nn::func(move |xs| {

let self_attn_output = xs.apply(&self_attn);

let x = xs + self_attn_output;

let x = x.apply(&layer_norm1);

let enc_dec_attn_output = x.apply(&enc_dec_attn);

let x = x + enc_dec_attn_output;

let x = x.apply(&layer_norm2);

let ff_output = x.apply(&feed_forward);

x + ff_output.apply(&layer_norm3)

})

}

/// Define the T5 Decoder

fn decoder(p: &nn::Path, n_embd: i64, n_layers: i64, n_heads: i64) -> impl Module {

let embedding = nn::embedding(p / "embedding", 32000, n_embd, Default::default());

let decoder_blocks: Vec<_> = (0..n_layers)

.map(|i| decoder_block(&p / format!("block_{}", i), n_embd, n_heads))

.collect();

nn::func(move |xs, encoder_output| {

let mut x = xs.apply(&embedding);

for block in &decoder_blocks {

x = x.apply(block);

}

x

})

}

/// Define the T5 model, combining encoder and decoder

fn t5_model(vs: &nn::Path, n_embd: i64, n_layers: i64, n_heads: i64) -> impl Module {

let encoder = encoder(vs / "encoder", n_embd, n_layers, n_heads);

let decoder = decoder(vs / "decoder", n_embd, n_layers, n_heads);

nn::func(move |src, tgt| {

let encoder_output = encoder.forward(&src);

decoder.forward(&tgt, &encoder_output)

})

}

/// Example function to train the T5 model with a dataset

fn train_t5_model() -> Result<(), Box<dyn std::error::Error>> {

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(Device::Cpu);

let t5 = t5_model(&vs.root(), 512, 6, 8);

let mut opt = nn::Adam::default().build(&vs, 1e-4)?;

// Example data loading step (replace with actual dataset loading)

let src = Tensor::randn(&[64, 128], (tch::Kind::Int64, Device::Cpu)); // dummy input

let tgt = Tensor::randn(&[64, 128], (tch::Kind::Int64, Device::Cpu)); // dummy target

for epoch in 0..100 {

let output = t5.forward(&src, &tgt);

// Example loss calculation (replace with actual criterion)

let loss = output.mean(tch::Kind::Float);

// Optimize

opt.backward_step(&loss);

println!("Epoch: {} | Loss: {:?}", epoch, f64::from(loss));

}

Ok(())

}

fn main() -> Result<(), Box<dyn std::error::Error>> {

train_t5_model()

}

Training the T5 model on multiple NLP tasks simultaneously can be done by first pre-training the model on a large corpus of unlabeled data and then fine-tuning it on task-specific datasets. The multitask learning capability of T5 allows it to perform well on a variety of tasks, and training can be done by alternating between different tasks or by using a task-specific loss function that balances the contributions of each task. For example, in a multitask setup involving translation, summarization, and sentiment analysis, the loss function might be a weighted sum of the individual task losses:

$$ \mathcal{L}_{\text{multitask}} = \lambda_1 \mathcal{L}_{\text{translation}} + \lambda_2 \mathcal{L}_{\text{summarization}} + \lambda_3 \mathcal{L}_{\text{sentiment}}, $$

where $\lambda_1, \lambda_2, \lambda_3$ are the weights that control the importance of each task. Fine-tuning T5 in Rust can be done by adjusting these weights and optimizing the model using gradient descent.

Fine-tuning T5 on specific tasks using Rust involves loading pre-trained weights into the T5 model and further training it on task-specific data. Fine-tuning enables the model to adapt to the nuances of a particular task, such as generating summaries that are concise and informative or translating sentences with high accuracy. The performance of the fine-tuned model can be evaluated by comparing it with task-specific models that have been trained from scratch. In most cases, the fine-tuned T5 model outperforms task-specific models, as it benefits from the general language understanding it gained during pre-training.

In industry, T5 has been applied to a wide range of tasks, from machine translation and summarization to question answering and dialogue generation. Its unified framework makes it particularly attractive for companies that need a versatile model capable of handling multiple NLP tasks with minimal modification. By using T5, organizations can simplify their NLP pipelines, as the same model can be fine-tuned and deployed for different use cases without needing to retrain separate models for each task.

Recent trends in multitask learning and unified models, such as T5, emphasize the importance of large-scale pre-training and efficient fine-tuning strategies. Researchers are increasingly focused on scaling up these models and finding ways to reduce their computational footprint, making them more accessible for real-time applications. Techniques like model distillation, quantization, and sparse training are being explored to make large models like T5 more resource-efficient while maintaining their strong performance across diverse tasks.

Lets see a practical example. This code initializes a language model based on the T5 architecture, specifically configured for translation and text generation tasks. It loads pre-trained model weights and tokenizer configurations from Hugging Face's hub, processes a specified prompt, and generates output either by encoding the prompt or by decoding it for conditional generation. Key parameters, such as temperature and repeat penalties, help guide the generation style, and the code uses hardcoded options for flexibility in configuring the device, model type, and other settings.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0"

serde_json = "1.0.132"

tch = "0.12.0"

reqwest = { version = "0.12.8", features = ["blocking"] }

candle-transformers = "0.7.2"

candle-core = "0.7.2"

candle-nn = "0.7.2"

hf-hub = "0.3.2"

tokenizers = "0.20.1"

accelerate-src = "0.3.2"

use candle_core::backend::BackendDevice;

use std::io::Write;

use std::path::PathBuf;

use candle_transformers::models::t5;

use anyhow::{anyhow, Result};

use candle_core::{DType, Device, Tensor, CudaDevice};

use candle_nn::VarBuilder;

use candle_transformers::generation::LogitsProcessor;

use hf_hub::{api::sync::Api, Repo, RepoType};

use tokenizers::Tokenizer;

const DTYPE: DType = DType::F32;

// Hardcoded configurations

const USE_CPU: bool = true;

const MODEL_ID: &str = "t5-small";

const REVISION: &str = "main";

const PROMPT: &str = "Translate English to French: How are you?";

const DECODE: bool = true;

const DISABLE_CACHE: bool = false;

const TEMPERATURE: f64 = 0.8;

const TOP_P: Option<f64> = None;

const REPEAT_PENALTY: f32 = 1.1;

const REPEAT_LAST_N: usize = 64;

const MAX_TOKENS: usize = 512;

struct T5ModelBuilder {

device: Device,

config: t5::Config,

weights_filename: Vec<PathBuf>,

}

impl T5ModelBuilder {

pub fn load() -> Result<(Self, Tokenizer)> {

let device = if USE_CPU { Device::Cpu } else { Device::Cuda(CudaDevice::new(0)?) };

let model_id = MODEL_ID.to_string();

let revision = REVISION.to_string();

let repo = Repo::with_revision(model_id.clone(), RepoType::Model, revision);

let api = Api::new()?;

let repo = api.repo(repo);

let config_filename = repo.get("config.json")?;

let tokenizer_filename = repo.get("tokenizer.json")?;

let weights_filename = vec![repo.get("model.safetensors")?];

let config = std::fs::read_to_string(config_filename)?;

let mut config: t5::Config = serde_json::from_str(&config)?;

config.use_cache = !DISABLE_CACHE;

// Load the tokenizer without additional modifications.

let tokenizer = Tokenizer::from_file(tokenizer_filename).map_err(|e| anyhow!(e))?;

Ok((

Self {

device,

config,

weights_filename,

},

tokenizer,

))

}

pub fn build_encoder(&self) -> Result<t5::T5EncoderModel> {

let vb = unsafe {

VarBuilder::from_mmaped_safetensors(&self.weights_filename, DTYPE, &self.device)?

};

Ok(t5::T5EncoderModel::load(vb, &self.config)?)

}

pub fn build_conditional_generation(&self) -> Result<t5::T5ForConditionalGeneration> {

let vb = unsafe {

VarBuilder::from_mmaped_safetensors(&self.weights_filename, DTYPE, &self.device)?

};

Ok(t5::T5ForConditionalGeneration::load(vb, &self.config)?)

}

}

fn main() -> Result<()> {

let (builder, tokenizer) = T5ModelBuilder::load()?;

let device = &builder.device;

// Tokenize with padding and truncation applied directly here.

let tokens = tokenizer

.encode(PROMPT, true)

.map_err(|e| anyhow!("Tokenization failed: {}", e))?

.get_ids()

.to_vec();

let input_token_ids = Tensor::new(&tokens[..], device)?.unsqueeze(0)?;

if !DECODE {

let mut model = builder.build_encoder()?;

let ys = model.forward(&input_token_ids)?;

println!("{ys}");

} else {

let mut model = builder.build_conditional_generation()?;

let mut output_token_ids = vec![

builder.config.decoder_start_token_id.unwrap_or(builder.config.pad_token_id) as u32,

];

let temperature = if TEMPERATURE <= 0.0 { None } else { Some(TEMPERATURE) };

let mut logits_processor = LogitsProcessor::new(299792458, temperature, TOP_P);

let encoder_output = model.encode(&input_token_ids)?;

for index in 0.. {

if output_token_ids.len() > MAX_TOKENS {

break;

}

let decoder_token_ids = if index == 0 || !builder.config.use_cache {

Tensor::new(output_token_ids.as_slice(), device)?.unsqueeze(0)?

} else {

let last_token = *output_token_ids.last().unwrap();

Tensor::new(&[last_token], device)?.unsqueeze(0)?

};

let logits = model.decode(&decoder_token_ids, &encoder_output)?.squeeze(0)?;

let logits = if REPEAT_PENALTY == 1.0 {

logits

} else {

let start_at = output_token_ids.len().saturating_sub(REPEAT_LAST_N);

candle_transformers::utils::apply_repeat_penalty(

&logits,

REPEAT_PENALTY,

&output_token_ids[start_at..],

)?

};

let next_token_id = logits_processor.sample(&logits)?;

if next_token_id as usize == builder.config.eos_token_id {

break;

}

output_token_ids.push(next_token_id);

if let Some(text) = tokenizer.id_to_token(next_token_id) {

let text = text.replace('▁', " ").replace("<0x0A>", "\n");

print!("{text}");

std::io::stdout().flush()?;

}

}

println!("\n{} tokens generated", output_token_ids.len());

}

Ok(())

}

pub fn normalize_l2(v: &Tensor) -> Result<Tensor> {

Ok(v.broadcast_div(&v.sqr()?.sum_keepdim(1)?.sqrt()?)?)

}

The program begins by defining and loading the model and tokenizer files. If set to decode, it uses a loop to iteratively generate tokens based on the prompt, with logits adjustments applied to manage repetition and randomness in the output. In encoding mode, the code simply processes the input through the encoder and displays the output embeddings. The tokenizer is configured with padding and truncation options, and final token outputs are decoded back into text for display. Constants control the model's behavior, such as device allocation (CPU/GPU), generation temperature, and token penalties, allowing a flexible setup without command-line input.

In conclusion, the T5 architecture is a powerful example of a multitask learning framework that can handle a variety of NLP tasks within a unified text-to-text paradigm. Its encoder-decoder structure and ability to share knowledge across tasks make it an ideal candidate for multitask learning scenarios. Implementing and fine-tuning T5 in Rust offers a highly efficient and scalable approach to solving NLP problems, leveraging Rust’s performance advantages while ensuring the model can generalize across different tasks effectively.u

7.3. Unified Models for Multitask Learning

Unified models in multitask learning represent a significant advancement in the field of natural language processing, where the goal is to design a single model architecture that can handle a variety of tasks without requiring modifications or task-specific components. These models offer a flexible and scalable solution, enabling developers to deploy a single model across multiple tasks, simplifying both deployment and maintenance. Unlike traditional models that are often trained separately for individual tasks, unified models leverage shared knowledge and representations, making them more efficient and adaptable. The T5 model is one example of a successful unified model, but others, such as mT5, BART, and UnifiedQA, demonstrate the versatility and power of task-agnostic architectures.

The fundamental principle behind unified models is the use of a shared architecture that remains consistent across tasks. In such models, tasks are treated in a similar way, with a common architecture handling diverse inputs and outputs. This approach reduces the complexity of training and deploying multiple models for different tasks, as the same architecture can be fine-tuned or adapted to perform well on each task. For example, mT5 extends the T5 framework to support multiple languages, treating multilingual translation, summarization, and question answering as variants of the same underlying task structure. This task-agnostic design is particularly useful in environments where models need to handle a broad range of tasks with minimal adjustments.

One of the key advantages of unified models is that they simplify model deployment and maintenance. In traditional systems, deploying separate models for different tasks requires maintaining multiple versions of the model, each trained and optimized individually. This introduces challenges in scaling and updating the models as new tasks emerge. By contrast, a unified model can be deployed once and fine-tuned as needed for additional tasks. This reduces the computational and operational overhead associated with maintaining task-specific architectures and makes scaling much easier. The uniform structure of unified models also makes it possible to apply the same optimization and efficiency techniques, such as quantization and pruning, across all tasks.

However, designing a unified model that performs well across a wide range of tasks presents significant challenges. One of the primary difficulties is ensuring that the model does not overfit to one task while underperforming on others, a problem known as task interference. When tasks are too dissimilar, the shared layers of the model may struggle to represent all tasks effectively, leading to suboptimal performance. Mathematically, this challenge can be expressed through the multitask loss function, where the model must minimize a combined loss across multiple tasks:

$$ \mathcal{L}_{\text{unified}} = \sum_{i=1}^{n} \lambda_i \mathcal{L}_i, $$

where $\mathcal{L}_i$ represents the loss for task $i$, and $\lambda_i$ controls the relative importance of each task. Finding the right balance for the task weights $\lambda_i$ is crucial to prevent one task from dominating the optimization process. In practice, techniques such as dynamic task weighting or task-specific layer modulation are often employed to mitigate these issues, allowing the model to adjust its parameters dynamically based on the current task.

Modular architectures have emerged as a solution to some of the challenges posed by unified models. In a modular framework, the model consists of shared components that are used across tasks, but also task-specific modules that can be activated when necessary. This allows the model to maintain a degree of specialization while benefiting from the generalization provided by the shared components. For example, a unified model might use the same encoder across all tasks but employ different decoders depending on the task, allowing for greater flexibility while still sharing the majority of the parameters. This modular approach can be formalized as:

$$ y_i = f_{\text{task}_i}(f_{\text{shared}}(x)), $$

where $f_{\text{shared}}(x)$ represents the shared encoder, and $f_{\text{task}_i}(x)$ represents the task-specific decoder for task $i$. By isolating the task-specific components, modular architectures offer a way to handle task interference while preserving the benefits of a unified model.

Parameter-efficient training is another key concept in the design of unified models. Given the large size of models like T5 or BART, training and fine-tuning these models across multiple tasks can be computationally expensive. Techniques like parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) and low-rank adaptation (LoRA) have been developed to reduce the number of parameters that need to be updated during training. In LoRA, for example, the model's weight matrices are factorized into lower-rank matrices, reducing the number of trainable parameters while maintaining the model's expressive power. The objective function for training under LoRA can be written as:

$$ W = W_0 + \Delta W = W_0 + A B, $$

where $W_0$ is the original pre-trained weight matrix, $\Delta W$ is the learned update, and $A$ and $B$ are the low-rank matrices. This technique allows unified models to be fine-tuned efficiently on new tasks without the need to retrain the entire model, making it particularly useful in multitask learning.

Unified models like BART (Bidirectional and Auto-Regressive Transformers) take a different approach by combining bidirectional encoding and autoregressive decoding, which makes the model versatile in handling both generative tasks (like summarization) and discriminative tasks (like classification). BART uses a similar encoder-decoder framework as T5, but with a focus on reconstructing corrupted input sequences, which helps the model learn strong representations for both understanding and generating text. This structure enables BART to perform well across a variety of tasks while maintaining a unified model architecture.

The provided Rust code is a text summarization script using Hugging Face's Rust-BERT library and the DistilBART model, specifically designed to run on CPU using the tch crate for PyTorch bindings in Rust. This script imports necessary resources and dependencies, such as model configuration, vocabulary, and merges files, which it retrieves remotely from Hugging Face’s pre-trained model repository. The code sets up a summarization configuration, defining parameters like beam search, length penalty, minimum and maximum token lengths, and then processes a long input text to produce a summary output. The main function also prints each summarized sentence to the console.

use anyhow;

use rust_bert::bart::{

BartConfigResources, BartMergesResources, BartModelResources, BartVocabResources,

};

use rust_bert::pipelines::common::ModelResource;

use rust_bert::pipelines::summarization::{SummarizationConfig, SummarizationModel};

use rust_bert::resources::RemoteResource;

use tch::Device;

fn main() -> anyhow::Result<()> {

let config_resource = Box::new(RemoteResource::from_pretrained(

BartConfigResources::DISTILBART_CNN_6_6,

));

let vocab_resource = Box::new(RemoteResource::from_pretrained(

BartVocabResources::DISTILBART_CNN_6_6,

));

let merges_resource = Box::new(RemoteResource::from_pretrained(

BartMergesResources::DISTILBART_CNN_6_6,

));

let model_resource = Box::new(RemoteResource::from_pretrained(

BartModelResources::DISTILBART_CNN_6_6,

));

let summarization_config = SummarizationConfig {

model_resource: ModelResource::Torch(model_resource),

config_resource,

vocab_resource,

merges_resource: Some(merges_resource),

num_beams: 1,

length_penalty: 1.0,

min_length: 56,

max_length: Some(142),

device: Device::Cpu,

..Default::default()

};

let summarization_model = SummarizationModel::new(summarization_config)?;

let input = ["In findings published Tuesday in Cornell University's arXiv by a team of scientists \

from the University of Montreal and a separate report published Wednesday in Nature Astronomy by a team \

from University College London (UCL), the presence of water vapour was confirmed in the atmosphere of K2-18b, \

a planet circling a star in the constellation Leo. This is the first such discovery in a planet in its star's \

habitable zone — not too hot and not too cold for liquid water to exist. The Montreal team, led by Björn Benneke, \

used data from the NASA's Hubble telescope to assess changes in the light coming from K2-18b's star as the planet \

passed between it and Earth. They found that certain wavelengths of light, which are usually absorbed by water, \

weakened when the planet was in the way, indicating not only does K2-18b have an atmosphere, but the atmosphere \

contains water in vapour form. The team from UCL then analyzed the Montreal team's data using their own software \

and confirmed their conclusion. This was not the first time scientists have found signs of water on an exoplanet, \

but previous discoveries were made on planets with high temperatures or other pronounced differences from Earth. \

\"This is the first potentially habitable planet where the temperature is right and where we now know there is water,\" \

said UCL astronomer Angelos Tsiaras. \"It's the best candidate for habitability right now.\" \"It's a good sign\", \

said Ryan Cloutier of the Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, who was not one of either study's authors. \

\"Overall,\" he continued, \"the presence of water in its atmosphere certainly improves the prospect of K2-18b being \

a potentially habitable planet, but further observations will be required to say for sure. \" \

K2-18b was first identified in 2015 by the Kepler space telescope. It is about 110 light-years from Earth and larger \

but less dense. Its star, a red dwarf, is cooler than the Sun, but the planet's orbit is much closer, such that a year \

on K2-18b lasts 33 Earth days. According to The Guardian, astronomers were optimistic that NASA's James Webb space \

telescope — scheduled for launch in 2021 — and the European Space Agency's 2028 ARIEL program, could reveal more \

about exoplanets like K2-18b."];

// Credits: WikiNews, CC BY 2.5 license (https://en.wikinews.org/wiki/Astronomers_find_water_vapour_in_atmosphere_of_exoplanet_K2-18b)

let _output = summarization_model.summarize(&input)?;

for sentence in _output {

println!("{sentence}");

}

Ok(())

}

In this code, SummarizationModel::new() initializes the model with the specified SummarizationConfig, leveraging DistilBART, a distilled version of the BART model fine-tuned for the CNN/DailyMail summarization task. The input text on exoplanet K2-18b is processed to condense its content, focusing on essential information. By using a high-level configuration structure, the script controls the summarization process, such as by limiting the summary length with min_length and max_length and adjusting num_beams for result diversity.

Experimenting with different task combinations in a unified model framework is an essential part of understanding the model’s ability to generalize. By training the model on diverse tasks—such as translation and summarization, or question answering and text classification—it is possible to evaluate how well the shared representations transfer between tasks. In some cases, tasks with similar structures or objectives will benefit from multitask learning, while dissimilar tasks may suffer from interference. Benchmarking these models against task-specific models can provide insights into the trade-offs between generalization and task specialization.

Lets see another code sample. This Rust code performs machine translation using the MBART-50 model from Hugging Face’s rust-bert library. MBART-50 is a multilingual sequence-to-sequence model capable of translating across numerous language pairs. The code imports resources for the model configuration, vocabulary, and language options for both source and target languages, all of which are retrieved remotely from Hugging Face's model repository. The main function initializes a translation configuration and sets up a TranslationModel with MBART-50, using GPU if available. The code then defines a source sentence in English and translates it into multiple languages, including French, Spanish, and Hindi, printing each translation to the console.

use anyhow;

use rust_bert::mbart::{

MBartConfigResources, MBartModelResources, MBartSourceLanguages, MBartTargetLanguages,

MBartVocabResources,

};

use rust_bert::pipelines::common::{ModelResource, ModelType};

use rust_bert::pipelines::translation::{Language, TranslationConfig, TranslationModel};

use rust_bert::resources::RemoteResource;

use tch::Device;

fn main() -> anyhow::Result<()> {

let model_resource = RemoteResource::from_pretrained(MBartModelResources::MBART50_MANY_TO_MANY);

let config_resource =

RemoteResource::from_pretrained(MBartConfigResources::MBART50_MANY_TO_MANY);

let vocab_resource = RemoteResource::from_pretrained(MBartVocabResources::MBART50_MANY_TO_MANY);

let source_languages = MBartSourceLanguages::MBART50_MANY_TO_MANY;

let target_languages = MBartTargetLanguages::MBART50_MANY_TO_MANY;

let translation_config = TranslationConfig::new(

ModelType::MBart,

ModelResource::Torch(Box::new(model_resource)),

config_resource,

vocab_resource,

None,

source_languages,

target_languages,

Device::cuda_if_available(),

);

let model = TranslationModel::new(translation_config)?;

let source_sentence = "This sentence will be translated in multiple languages.";

let mut outputs = Vec::new();

outputs.extend(model.translate(&[source_sentence], Language::English, Language::French)?);

outputs.extend(model.translate(&[source_sentence], Language::English, Language::Spanish)?);

outputs.extend(model.translate(&[source_sentence], Language::English, Language::Indonesian)?);

for sentence in outputs {

println!("{sentence}");

}

Ok(())

}

This script showcases TranslationConfig's flexibility in specifying source and target languages, allowing dynamic, language-to-language translation with MBART-50. By leveraging Language enums, the model can quickly switch between translations, showcasing the model's many-to-many translation capabilities. The setup includes device configuration to use GPU if available, enhancing translation speed. This script highlights efficient multilingual processing by outputting each translated sentence sequentially, demonstrating MBART's multilingual proficiency in a straightforward Rust implementation.

Unified models have seen increasing use in industry, where the ability to deploy a single model that can handle multiple tasks simplifies the deployment pipeline and reduces operational costs. For example, in customer service automation, a unified model could handle both intent classification and response generation, reducing the need to maintain separate models for each task. Similarly, in e-commerce platforms, unified models can be used for both product recommendation and customer sentiment analysis, streamlining the workflow and improving efficiency.

Recent trends in unified models emphasize the development of more efficient architectures that can handle larger numbers of tasks while maintaining strong performance. Advances in hardware acceleration, such as the use of TPUs and GPUs, have made it possible to train and deploy large-scale models like mT5 and UnifiedQA across multiple languages and tasks. Additionally, techniques like multitask pre-training and modular design are becoming more common, allowing models to handle an even wider range of tasks without sacrificing performance or efficiency.

In conclusion, unified models represent a powerful approach to multitask learning, offering the ability to handle diverse tasks within a single architecture. While challenges such as task interference and efficient fine-tuning remain, techniques like modular architectures and parameter-efficient training have made it possible to design flexible and scalable models. Implementing these models in Rust provides a performance-efficient way to explore multitask learning, allowing developers to optimize and deploy models that can generalize across a broad range of tasks. As the field evolves, unified models are likely to play a central role in the development of multitask learning systems.

7.4. Fine-Tuning Multitask Models for Specific Applications

Fine-tuning multitask models, such as T5, for specific applications is a crucial step in adapting pre-trained models to new domains or tasks while retaining their previously learned capabilities. Multitask models are typically pre-trained on large datasets spanning various tasks, enabling them to capture general language patterns and representations. However, for real-world applications like summarization or translation in specific domains (e.g., legal, medical), fine-tuning is essential to adapt the model to the nuances of the target domain. The process of fine-tuning takes advantage of the knowledge the model has already acquired during its pre-training and uses it to specialize in the new tasks with relatively less data and training time compared to training a model from scratch.

Mathematically, fine-tuning involves continuing to minimize the loss function of the model, but on a new task-specific dataset. Suppose Lpretrain\\mathcal{L}\_{\\text{pretrain}}Lpretrain represents the loss function used during the pre-training phase, which covers multiple tasks. During fine-tuning, we introduce a new task-specific loss Lnew\\mathcal{L}\_{\\text{new}}Lnew, and the objective is to minimize this new loss while maintaining the model’s performance on previously learned tasks. The new objective can be formulated as a combination of the pre-trained loss and the new task-specific loss:

$$ \mathcal{L}_{\text{fine-tune}} = \lambda_1 \mathcal{L}_{\text{new}} + \lambda_2 \mathcal{L}_{\text{pretrain}}, $$

where $\lambda_1$ and $\lambda_2$ are hyperparameters that control the balance between adapting the model to the new task and preserving the knowledge from pre-training. This formulation ensures that while the model is specialized for the new task, it does not completely forget its previous training, thus addressing one of the key challenges in fine-tuning: catastrophic forgetting.

Catastrophic forgetting occurs when a model fine-tuned on a new task loses its ability to perform well on tasks it previously learned. This happens because the model’s weights are updated too aggressively on the new task, overwriting the representations that were useful for other tasks. Techniques such as Elastic Weight Consolidation (EWC) or regularization-based methods help mitigate this issue. EWC introduces a regularization term to the loss function that penalizes significant changes in the weights that are important for previous tasks. This can be expressed as:

$$ \mathcal{L}_{\text{ewc}} = \mathcal{L}_{\text{new}} + \frac{\lambda}{2} \sum_i F_i (\theta_i - \theta_i^*)^2, $$

where $\theta_i$ represents the model's current weights, $\theta_i^*$ are the weights learned during pre-training, and $F_i$ is the Fisher information matrix, which measures the importance of each weight. This term penalizes changes to weights that are critical for previously learned tasks, helping the model retain its multitask capabilities.

Transfer learning plays a key role in the fine-tuning process. By leveraging the knowledge from pre-trained multitask models, transfer learning allows the model to quickly adapt to new tasks, even when the available data is limited. In low-resource scenarios, where only a small amount of domain-specific data is available, the model’s ability to transfer its general knowledge is particularly valuable. Fine-tuning in these cases typically involves using a much smaller learning rate, ensuring that the model does not drastically alter its pre-trained parameters but instead fine-tunes them to capture the specific nuances of the new task. This approach is especially effective when the new task is related to the tasks the model was pre-trained on, allowing for efficient knowledge transfer.

When fine-tuning multitask models on domain-specific data, one of the challenges is handling the variability and complexity of the data. Domain-specific tasks often introduce new vocabulary, specialized terminology, or unique sentence structures that the pre-trained model may not have encountered before. As a result, the model’s embeddings may need to be fine-tuned to handle the new distribution of text. In such cases, techniques like domain-adaptive pre-training (DAPT) can be employed, where the model undergoes an additional phase of pre-training on a domain-specific corpus before being fine-tuned on the target task. This helps the model better capture the specific characteristics of the domain and improves performance on domain-specific tasks.

This Rust code provides a structure for fine-tuning a simplified T5 model, specifically managing pre-trained weights by downloading them if they don’t already exist locally. It defines a t5_model with encoder and decoder blocks and sets up multi-head attention within these blocks. A download_weights function is incorporated to retrieve model weights from a specified URL and save them locally if not already present. The code then initializes and loads these weights into a VarStore, configures an Adam optimizer, and fine-tunes the model using placeholder data over multiple epochs. Loss values are output to track the training progress, and the final model is saved.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0"

serde_json = "1.0.132"

tch = "0.17.0"

reqwest = { version = "0.12.8", features = ["blocking"] }

use reqwest::blocking::get;

use std::{fs, io::Write, path::Path};

use tch::{nn, nn::Module, nn::OptimizerConfig, Device, Tensor};

/// Download the pre-trained weights file if it doesn't exist locally

fn download_weights(url: &str, output_path: &str) -> Result<(), Box<dyn std::error::Error>> {

if Path::new(output_path).exists() {

println!("Weights file already exists at '{}'", output_path);

return Ok(());

}

println!("Downloading weights from {}...", url);

let response = get(url)?;

let mut out = fs::File::create(output_path)?;

out.write_all(&response.bytes()?)?;

println!("Downloaded weights to '{}'", output_path);

Ok(())

}

/// Define a simplified multi-head attention structure

fn multi_head_attention(p: &nn::Path, n_embd: i64, _n_heads: i64) -> impl Module {

nn::seq()

.add(nn::linear(p / "query", n_embd, n_embd, Default::default()))

.add(nn::linear(p / "key", n_embd, n_embd, Default::default()))

.add(nn::linear(p / "value", n_embd, n_embd, Default::default()))

.add(nn::linear(p / "out", n_embd, n_embd, Default::default()))

}

/// Define a simplified T5 model structure for fine-tuning

fn t5_model(vs: &nn::Path, n_embd: i64, n_layers: i64, n_heads: i64) -> impl Module {

let encoder = encoder(&(vs / "encoder"), n_embd, n_layers, n_heads);

let decoder = decoder(&(vs / "decoder"), n_embd, n_layers, n_heads);

nn::func(move |src| {

let encoder_output = encoder.forward(&src);

decoder.forward(&encoder_output)

})

}

/// Load pre-trained weights for the T5 model