Chapter 6

‘Generative Models: GPT and Beyond’

"Generative models like GPT represent a leap forward in our ability to synthesize human-like text, reflecting the profound potential of AI to understand and generate complex language." — Yann LeCun

Chapter 6 of LMVR provides an in-depth exploration of generative models, with a particular focus on GPT and its variants. The chapter begins by introducing the basics of generative models, distinguishing them from discriminative models, and discussing their applications in natural language processing (NLP). It then delves into the GPT architecture, explaining its autoregressive nature, training process, and the benefits of leveraging Transformer models. The chapter also covers advancements in GPT variants, including GPT-2 and GPT-3, examining the impact of scaling on performance and the ethical considerations of deploying large models. Practical sections include implementing basic generative models in Rust, training GPT models, and comparing different GPT variants to understand their strengths and limitations.

6.1. Introduction to Generative Models

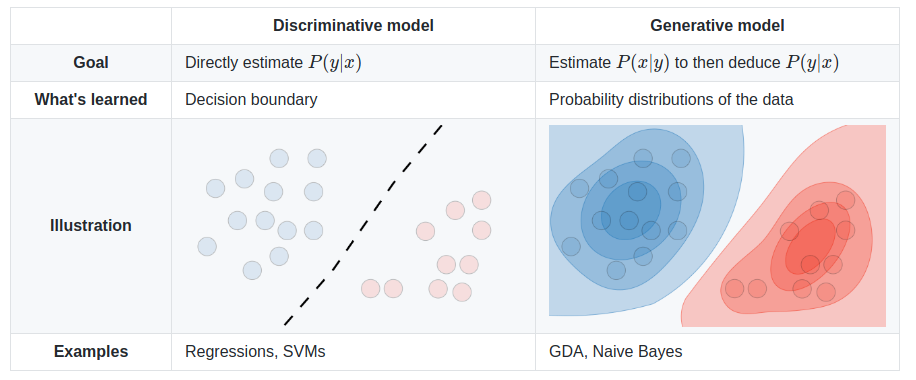

Generative models play a crucial role in machine learning by modeling the underlying distribution of data, allowing them to generate new instances that resemble the data they have been trained on. This contrasts with discriminative models, which focus on distinguishing between different classes of data. Generative models aim to understand and reproduce the data distribution itself, which makes them particularly useful in tasks like text generation, summarization, and translation in the domain of natural language processing (NLP). While discriminative models like classification networks are designed to assign labels or categories to inputs, generative models capture the structure and patterns within the data to create new, plausible outputs.

Figure 1: Discriminative vs Generative Models.

In the context of NLP, generative models have become fundamental in producing high-quality, human-like text. Their applications span from generating coherent sentences to summarizing vast amounts of information into concise, meaningful text, and even translating languages with remarkable accuracy. Models like GPT (Generative Pretrained Transformer) exemplify the capability of generative models to create fluid and contextually appropriate text based on a given input or prompt. These models do not merely generate random sequences; instead, they model language patterns, grammar, and semantics, producing text that often mirrors human expression.

At the core of generative models lies their ability to learn the distribution of data. This involves capturing the probability distribution $P(X)$, where $X$ represents the data, such as sentences in a corpus. For autoregressive models, the key idea is to factor the joint probability distribution of a sequence of words into a product of conditional probabilities. For example, in the case of text generation, the probability of the entire sequence is modeled as:

$$P(X) = P(x_1)P(x_2 | x_1)P(x_3 | x_1, x_2) \dots P(x_n | x_1, x_2, \dots, x_{n-1}),$$

where $x_i$ represents each word in the sequence. By learning these conditional probabilities, the model can generate new text one word at a time, based on the previously generated words.

Generative models like GPT utilize autoregressive methods, where the output at each step is conditioned on the previous tokens in the sequence. The Transformer architecture behind GPT has revolutionized generative modeling due to its efficient handling of long-range dependencies through self-attention mechanisms. In this self-attention mechanism, each token in the input sequence attends to all other tokens, enabling the model to capture both local and global patterns within the data. This allows models like GPT to generate coherent and contextually rich text by paying attention to all words in a sentence rather than just neighboring ones, as was the case with earlier models like recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and long short-term memory networks (LSTMs).

Another important concept powering modern generative models is self-supervised learning. In self-supervised learning, the model is trained on tasks where parts of the input data are masked or corrupted, and the model is asked to predict the missing parts. This type of training enables models to learn from vast amounts of unlabeled data, which is critical for large-scale generative models like GPT. By predicting missing words or phrases in a sentence, the model learns the relationships between words and the underlying structure of language. This technique forms the foundation of many state-of-the-art models in NLP today.

The practical implementation of generative models has traditionally been facilitated by frameworks like PyTorch and TensorFlow, but Rust is now gaining traction in the deep learning community due to its performance, low-level control, and memory safety benefits. In Rust, implementing a generative model for tasks like text generation can be achieved using libraries such as tch-rs, rust-bert, and candle. The tch-rs crate provides Rust bindings to PyTorch’s C++ backend, enabling seamless access to pre-trained models and custom training in Rust. Similarly, rust-bert leverages tch-rs to offer pre-trained transformer models, such as GPT-2, for text generation and other NLP tasks. The candle crate, on the other hand, is a native Rust deep learning framework that focuses on providing efficient model implementations and is increasingly being used for experimental and production applications in Rust.

To implement a generative model in Rust, one could use an autoregressive model like GPT-2, which predicts the next word in a sequence based on preceding words. The typical loss function for training such a model is cross-entropy loss, which measures the discrepancy between the predicted probability distribution over vocabulary and the true distribution (often represented by the actual next word). In an autoregressive setup, the model is trained to maximize the probability of each subsequent word in the sequence given the words that came before it. Rust’s performance and control over memory make it an ideal language for fine-tuning these models, enabling developers to implement memory-efficient generative models suitable for real-time or embedded applications.

One of the early challenges faced by generative models was the difficulty in generating coherent long-term sequences. RNNs and LSTMs struggled with maintaining consistency over long text due to their inherent limitations in modeling long-range dependencies. However, with the introduction of Transformer architectures and self-attention mechanisms, these challenges have been significantly mitigated. The Transformer’s ability to process the entire sequence at once, rather than sequentially, allows it to maintain coherence over much longer sequences.

Benchmarking a generative model against a simple baseline is essential for evaluating performance. In the case of text generation, one can compare the quality of the generated text using metrics such as perplexity, which measures how well the model predicts the next word in a sequence. A lower perplexity indicates better performance. Additionally, qualitative evaluations such as human judgment are often used to assess the fluency and coherence of the generated text.

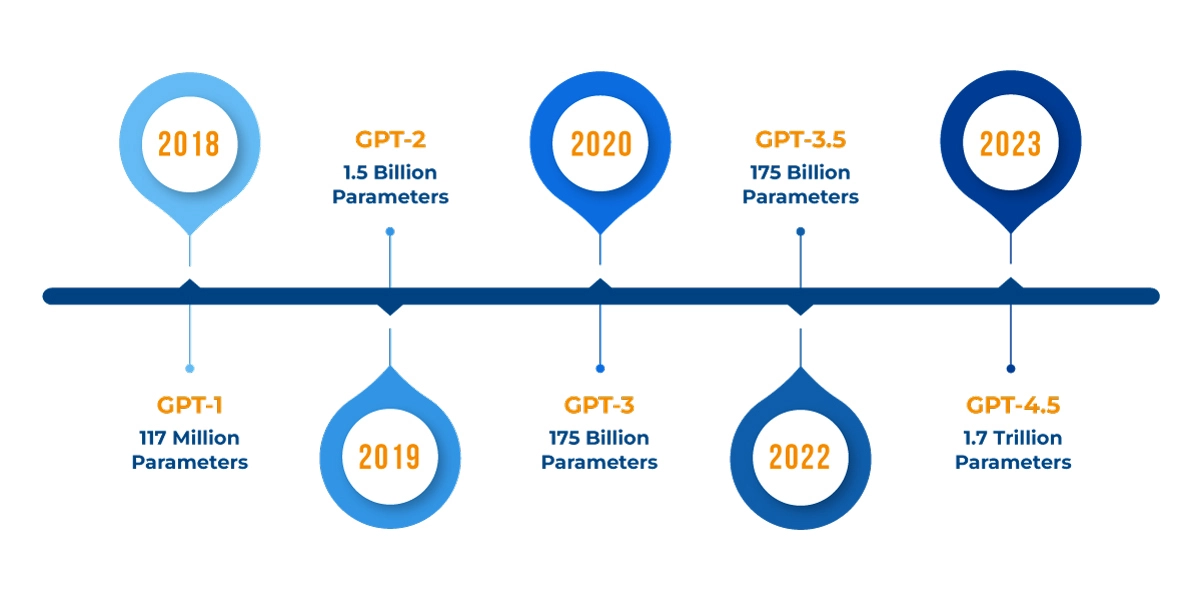

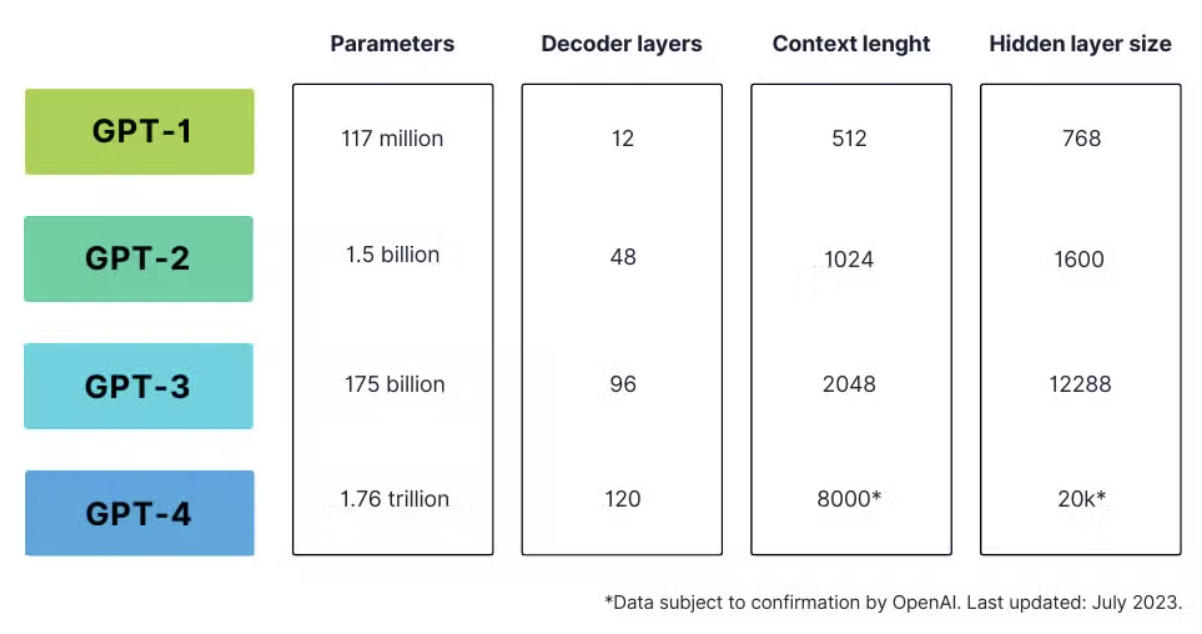

Since 2018, OpenAI's GPT models have seen a rapid increase in the number of parameters, reflecting advancements in model complexity, capacity, and performance. The original GPT, introduced in 2018, had around 117 million parameters and showcased the potential of transformer architectures in language tasks. A year later, GPT-2 scaled up significantly to 1.5 billion parameters, enhancing its ability to generate coherent and contextually aware text. In 2020, OpenAI released GPT-3, which further expanded to 175 billion parameters, allowing the model to handle even more nuanced language understanding and generation tasks across a broader range of topics. This growth in parameters is driven by the need for models to capture increasingly complex language patterns and world knowledge, which requires greater capacity and depth in neural networks. By scaling up parameters, OpenAI aims to improve the model's ability to generalize across diverse tasks with minimal fine-tuning, leveraging the sheer scale to encapsulate more linguistic and factual patterns directly within the model's architecture.

Figure 2: Numbers of parameters of GPT models.

Generative models have evolved rapidly in recent years, propelled by innovations like GPT and its successors. The latest developments focus on creating even larger models, such as GPT-4, which have billions of parameters and can generate text that often mirrors human writing. Additionally, there is growing interest in fine-tuning these models for specialized domains, such as legal or medical text generation, where domain-specific expertise is crucial. Future advancements are expected to extend beyond natural language processing (NLP) to include multimodal models capable of generating text, images, music, and video, broadening the applications and impact of these technologies.

This Rust program showcases the use of prompt engineering techniques with the langchain-rust library to optimize responses from OpenAI’s language models. Prompt engineering involves carefully designing input prompts to steer the model’s response style, tone, and structure. The program demonstrates various techniques, such as defining clear roles, controlling response length, incorporating conversation history, and applying few-shot learning examples. These methods enhance the model’s output by making it more accurate, contextually relevant, and aligned with specific user requirements, demonstrating the effectiveness of prompt engineering in fine-tuning generative model interactions.

[dependencies]

langchain-rust = "4.6.0"

serde_json = "1.0.132"

tokio = "1.41.0"

use langchain_rust::{

chain::{Chain, LLMChainBuilder},

fmt_message, fmt_placeholder, fmt_template,

language_models::llm::LLM,

llm::openai::{OpenAI, OpenAIModel},

message_formatter,

prompt::HumanMessagePromptTemplate,

prompt_args,

schemas::messages::Message,

template_fstring,

};

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() {

// Initialize the OpenAI model:

let open_ai = OpenAI::default().with_model(OpenAIModel::Gpt4oMini.to_string());

// Basic Prompt - Asking a simple question

let basic_response = open_ai.invoke("What is rust").await.unwrap();

println!("Basic Response: {}", basic_response);

// **1. Role Specification** - Specifying a Role with System Message

let role_prompt = message_formatter![

fmt_message!(Message::new_system_message(

"You are a world-class technical documentation writer with a deep knowledge of Rust programming."

)),

fmt_template!(HumanMessagePromptTemplate::new(template_fstring!(

"{input}", "input"

)))

];

let role_chain = LLMChainBuilder::new()

.prompt(role_prompt)

.llm(open_ai.clone())

.build()

.unwrap();

match role_chain

.invoke(prompt_args! {

"input" => "Explain Rust in simple terms.",

})

.await

{

Ok(result) => {

println!("Role-Specified Response: {:?}", result);

}

Err(e) => panic!("Error invoking role_chain: {:?}", e),

}

// **2. Response Formatting and Contextual Guidance**

let format_prompt = message_formatter![

fmt_message!(Message::new_system_message(

"You are a concise, professional technical writer. Answer in three bullet points."

)),

fmt_template!(HumanMessagePromptTemplate::new(template_fstring!(

"{input}", "input"

)))

];

let format_chain = LLMChainBuilder::new()

.prompt(format_prompt)

.llm(open_ai.clone())

.build()

.unwrap();

match format_chain

.invoke(prompt_args! {

"input" => "What are the key benefits of Rust?",

})

.await

{

Ok(result) => {

println!("Formatted Response: {:?}", result);

}

Err(e) => panic!("Error invoking format_chain: {:?}", e),

}

// **3. Few-Shot Learning Examples** - Providing Examples to Guide the Response

let few_shot_prompt = message_formatter![

fmt_message!(Message::new_system_message(

"You are an expert programmer. Answer in a friendly, concise tone."

)),

fmt_template!(HumanMessagePromptTemplate::new(template_fstring!(

"{input}", "input"

))),

fmt_message!(Message::new_human_message("Explain the difference between Rust and C++.")),

fmt_message!(Message::new_ai_message("Rust focuses on memory safety without a garbage collector, whereas C++ provides more control but with greater risk of memory errors.")),

];

let few_shot_chain = LLMChainBuilder::new()

.prompt(few_shot_prompt)

.llm(open_ai.clone())

.build()

.unwrap();

match few_shot_chain

.invoke(prompt_args! {

"input" => "What makes Rust different from Python?",

})

.await

{

Ok(result) => {

println!("Few-Shot Response: {:?}", result);

}

Err(e) => panic!("Error invoking few_shot_chain: {:?}", e),

}

// **4. Historical Context** - Adding Conversation History

let history_prompt = message_formatter![

fmt_message!(Message::new_system_message(

"You are a helpful assistant that remembers context."

)),

fmt_placeholder!("history"),

fmt_template!(HumanMessagePromptTemplate::new(template_fstring!(

"{input}", "input"

))),

];

let history_chain = LLMChainBuilder::new()

.prompt(history_prompt)

.llm(open_ai.clone())

.build()

.unwrap();

match history_chain

.invoke(prompt_args! {

"input" => "Who is the writer of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea?",

"history" => vec![

Message::new_human_message("My name is Luis."),

Message::new_ai_message("Hi Luis, nice to meet you!"),

Message::new_human_message("Can you also tell me who wrote 'Around the World in 80 Days'?"),

Message::new_ai_message("That would be Jules Verne, the famous French author."),

],

})

.await

{

Ok(result) => {

println!("History-Based Response: {:?}", result);

}

Err(e) => panic!("Error invoking history_chain: {:?}", e),

}

// **5. Instructional Prompt for Output Length** - Limiting Response Length

let length_prompt = message_formatter![

fmt_message!(Message::new_system_message(

"You are a Rust expert. Provide a response that is no more than three sentences."

)),

fmt_template!(HumanMessagePromptTemplate::new(template_fstring!(

"{input}", "input"

)))

];

let length_chain = LLMChainBuilder::new()

.prompt(length_prompt)

.llm(open_ai.clone())

.build()

.unwrap();

match length_chain

.invoke(prompt_args! {

"input" => "What is Rust and why is it popular?",

})

.await

{

Ok(result) => {

println!("Length-Limited Response: {:?}", result);

}

Err(e) => panic!("Error invoking length_chain: {:?}", e),

}

// **6. Contextual Prompts with Additional Hints** - Providing Specific Hints

let contextual_prompt = message_formatter![

fmt_message!(Message::new_system_message(

"You are a knowledgeable assistant. Answer the following question with a focus on security and performance."

)),

fmt_template!(HumanMessagePromptTemplate::new(template_fstring!(

"{input}", "input"

)))

];

let contextual_chain = LLMChainBuilder::new()

.prompt(contextual_prompt)

.llm(open_ai)

.build()

.unwrap();

match contextual_chain

.invoke(prompt_args! {

"input" => "Why do developers choose Rust over other languages?",

})

.await

{

Ok(result) => {

println!("Contextual Response: {:?}", result);

}

Err(e) => panic!("Error invoking contextual_chain: {:?}", e),

}

}

The code begins by initializing an instance of OpenAI’s language model and then defines multiple prompt templates, each incorporating a different prompt engineering technique. Each template is structured with specific instructions for the model, such as assigning a technical writer’s role, formatting responses as concise bullet points, and using prior conversation history to provide context for more personalized interactions. These templates are then combined into LLMChains, which allow the model to be invoked with a prompt tailored to each technique. For example, the history_chain includes conversation history in the prompt to create contextually aware responses, while the few_shot_chain includes sample questions and answers to encourage consistency in style and relevance. By systematically applying these techniques, the code demonstrates how to steer the model’s behavior to produce responses that better match specific goals and communication needs.

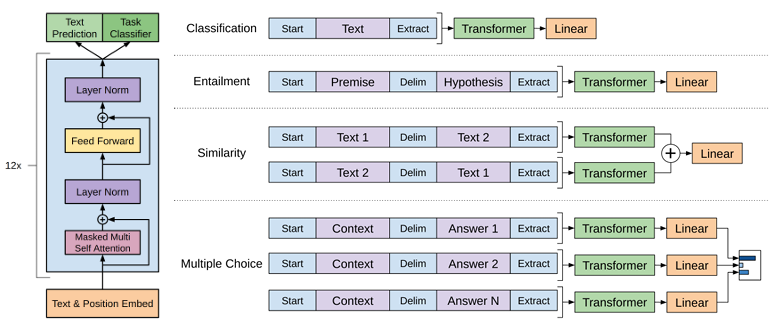

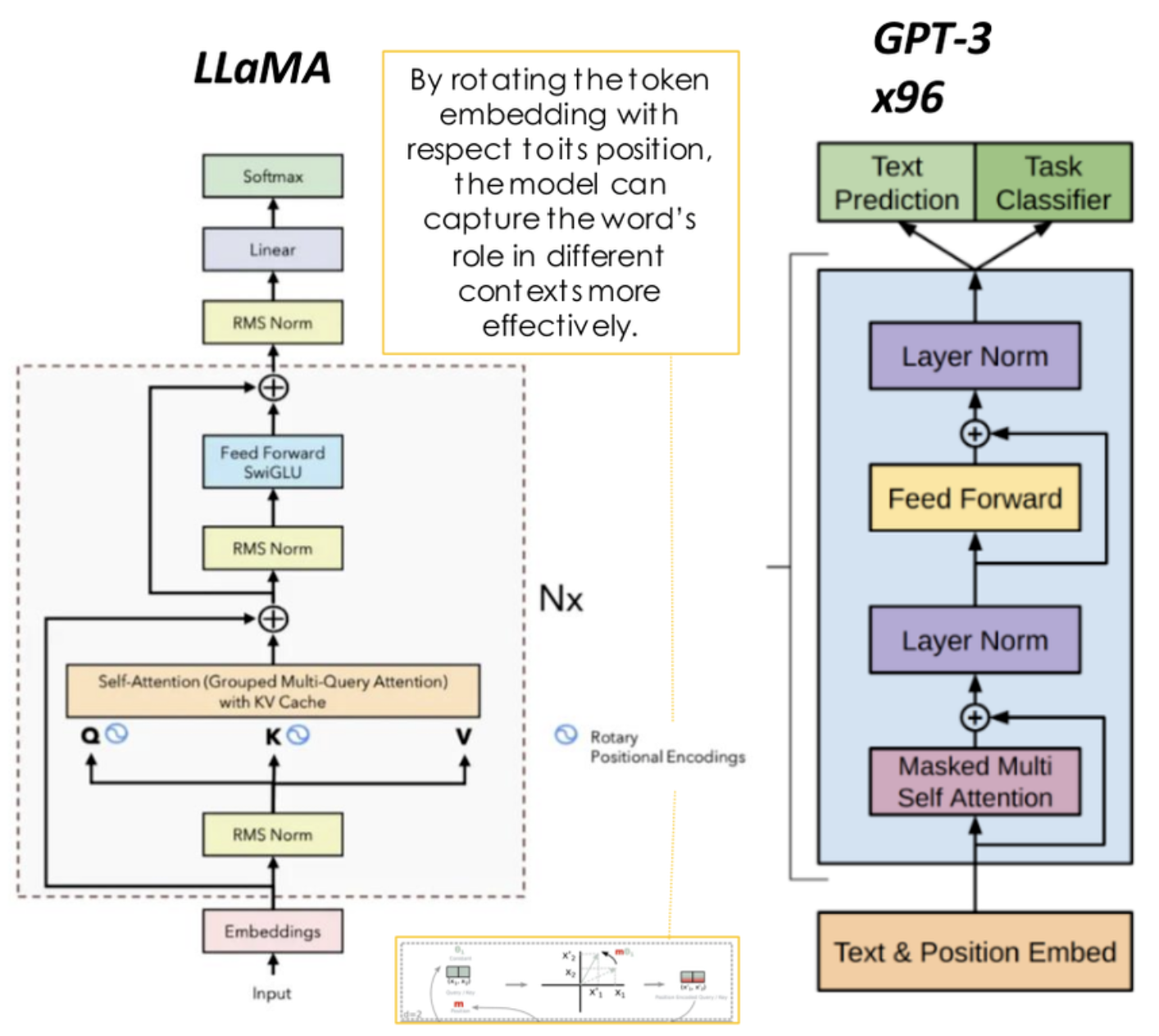

6.2. The GPT Architecture

The GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer) architecture has revolutionized the landscape of natural language processing by enabling powerful generative capabilities, particularly in text generation. At its core, GPT is built upon the Transformer architecture, which was originally introduced in the seminal paper Attention is All You Need. GPT models leverage this architecture, focusing on autoregressive text generation, where each subsequent word in a sequence is predicted based on all the preceding words. This approach allows GPT models to generate coherent, contextually relevant text in a sequential manner.

Figure 3: Illustration of GPT-2 architecture.

Autoregression is a fundamental concept in GPT. The model generates text one token at a time, using the probability distribution of the next token conditioned on the previous tokens. Mathematically, this process can be described by the following formula for generating a sequence $x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n$:

$$P(x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n) = \prod_{i=1}^{n} P(x_i | x_1, x_2, \dots, x_{i-1}),$$

where each token $x_i$ is generated based on the tokens that precede it. GPT's autoregressive mechanism ensures that the model captures the dependencies and relationships between words, enabling it to produce fluent and coherent sentences. This is achieved by encoding the entire context of the preceding tokens using a self-attention mechanism, which enables the model to learn both short-range and long-range dependencies within a text sequence.

The training process of GPT involves two primary stages: pre-training and fine-tuning. During the pre-training phase, the model is trained on a large corpus of text using unsupervised learning. The objective is to predict the next token in a sequence given the previous tokens, commonly referred to as a language modeling task. The loss function used in this stage is the negative log-likelihood of the predicted token probabilities:

$$\mathcal{L} = - \sum_{i=1}^{n} \log P(x_i | x_1, x_2, \dots, x_{i-1}),$$

where the model is optimized to minimize this loss over the training data. Tokenization, the process of converting text into smaller components (tokens), is a crucial aspect of GPT's training process. GPT typically uses subword tokenization methods like Byte Pair Encoding (BPE), which strike a balance between character-level and word-level tokenization, enabling the model to handle out-of-vocabulary words and efficiently process large vocabularies.

The Transformer architecture, which powers GPT, relies heavily on self-attention mechanisms to encode the relationships between tokens in a sequence. In the case of GPT, the architecture consists of multiple layers of self-attention blocks followed by feedforward networks. The self-attention mechanism computes a set of attention scores for each token, determining how much focus the model should place on other tokens when generating the next one. The self-attention function for a single token is computed as:

$$\text{Attention}(Q, K, V) = \text{softmax}\left(\frac{QK^T}{\sqrt{d_k}}\right)V,$$

where $Q$ (query), $K$ (key), and $V$ (value) are matrices derived from the input tokens, and $d_k$ is the dimensionality of the query and key vectors. This mechanism allows GPT to consider all tokens in the sequence when generating the next token, rather than relying solely on local context. This capacity to capture long-range dependencies is a key reason for the model's ability to generate coherent and contextually rich text.

Large-scale pre-training is a crucial factor in the success of GPT models. By training on vast amounts of diverse data, GPT develops a broad understanding of language that it can apply to a wide range of downstream tasks. After pre-training, the model can be fine-tuned on specific tasks, such as text completion, summarization, or dialogue generation, using a relatively small amount of task-specific labeled data. Fine-tuning adjusts the model weights to optimize performance for the given task while retaining the knowledge acquired during the pre-training phase. This transfer learning approach enables GPT to achieve state-of-the-art performance across many NLP benchmarks.

However, while the GPT architecture excels in generating fluent text, it has some notable limitations. One major challenge is that GPT models are prone to generating plausible but incorrect or nonsensical information, a phenomenon known as hallucination. This occurs because GPT is trained to predict the next word based on probabilities derived from the training data, rather than verifying the factual correctness of the content. Additionally, GPT models have difficulty handling tasks that require complex reasoning or deep understanding of context over extended passages, and they may struggle with tasks that involve maintaining consistency over very long sequences, such as multi-turn conversations.

This Rust program is an implementation of a GPT-like text generation model using the tch-rs crate, which provides Rust bindings to PyTorch. The model, similar to Andrej Karpathy’s minGPT, is trained on the tinyshakespeare dataset. This dataset, available as a simple text file, allows the model to learn how to predict the next character based on previous characters, ultimately enabling it to generate coherent text sequences. The code includes both training and inference (prediction) functionalities, making it a complete example of an autoregressive language model in Rust.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0.90"

tch = "0.12.0"

/* This example uses the tinyshakespeare dataset which can be downloaded at:

https://raw.githubusercontent.com/karpathy/char-rnn/master/data/tinyshakespeare/input.txt

This is mostly a rust port of https://github.com/karpathy/minGPT

*/

use anyhow::{bail, Result};

use tch::data::TextData;

use tch::nn::{ModuleT, OptimizerConfig};

use tch::{nn, Device, IndexOp, Kind, Tensor};

const LEARNING_RATE: f64 = 0.0003;

const BLOCK_SIZE: i64 = 128;

const BATCH_SIZE: i64 = 64;

const EPOCHS: i64 = 100;

const SAMPLING_LEN: i64 = 4096;

#[derive(Debug, Copy, Clone)]

struct Config {

vocab_size: i64,

n_embd: i64,

n_head: i64,

n_layer: i64,

block_size: i64,

attn_pdrop: f64,

resid_pdrop: f64,

embd_pdrop: f64,

}

// Weight decay only applies to the weight matrixes in the linear layers

const NO_WEIGHT_DECAY_GROUP: usize = 0;

const WEIGHT_DECAY_GROUP: usize = 1;

// Custom linear layer so that different groups can be used for weight

// and biases.

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Linear {

pub ws: Tensor,

pub bs: Tensor,

}

impl nn::Module for Linear {

fn forward(&self, xs: &Tensor) -> Tensor {

xs.matmul(&self.ws.tr()) + &self.bs

}

}

fn linear(vs: nn::Path, in_dim: i64, out_dim: i64) -> Linear {

let wd = vs.set_group(WEIGHT_DECAY_GROUP);

let no_wd = vs.set_group(NO_WEIGHT_DECAY_GROUP);

Linear {

ws: wd.randn("weight", &[out_dim, in_dim], 0.0, 0.02),

bs: no_wd.zeros("bias", &[out_dim]),

}

}

fn linear_no_bias(vs: nn::Path, in_dim: i64, out_dim: i64) -> Linear {

let wd = vs.set_group(WEIGHT_DECAY_GROUP);

let no_wd = vs.set_group(NO_WEIGHT_DECAY_GROUP);

Linear {

ws: wd.randn("weight", &[out_dim, in_dim], 0.0, 0.02),

bs: no_wd.zeros_no_train("bias", &[out_dim]),

}

}

fn causal_self_attention(p: &nn::Path, cfg: Config) -> impl ModuleT {

let key = linear(p / "key", cfg.n_embd, cfg.n_embd);

let query = linear(p / "query", cfg.n_embd, cfg.n_embd);

let value = linear(p / "value", cfg.n_embd, cfg.n_embd);

let proj = linear(p / "proj", cfg.n_embd, cfg.n_embd);

let mask_init =

Tensor::ones([cfg.block_size, cfg.block_size], (Kind::Float, p.device())).tril(0);

let mask_init = mask_init.view([1, 1, cfg.block_size, cfg.block_size]);

// let mask = p.var_copy("mask", &mask_init);

let mask = mask_init;

nn::func_t(move |xs, train| {

let (sz_b, sz_t, sz_c) = xs.size3().unwrap();

let sizes = [sz_b, sz_t, cfg.n_head, sz_c / cfg.n_head];

let k = xs.apply(&key).view(sizes).transpose(1, 2);

let q = xs.apply(&query).view(sizes).transpose(1, 2);

let v = xs.apply(&value).view(sizes).transpose(1, 2);

let att = q.matmul(&k.transpose(-2, -1)) * (1.0 / f64::sqrt(sizes[3] as f64));

let att = att.masked_fill(&mask.i((.., .., ..sz_t, ..sz_t)).eq(0.), f64::NEG_INFINITY);

let att = att.softmax(-1, Kind::Float).dropout(cfg.attn_pdrop, train);

let ys = att.matmul(&v).transpose(1, 2).contiguous().view([sz_b, sz_t, sz_c]);

ys.apply(&proj).dropout(cfg.resid_pdrop, train)

})

}

fn block(p: &nn::Path, cfg: Config) -> impl ModuleT {

let ln1 = nn::layer_norm(p / "ln1", vec![cfg.n_embd], Default::default());

let ln2 = nn::layer_norm(p / "ln2", vec![cfg.n_embd], Default::default());

let attn = causal_self_attention(p, cfg);

let lin1 = linear(p / "lin1", cfg.n_embd, 4 * cfg.n_embd);

let lin2 = linear(p / "lin2", 4 * cfg.n_embd, cfg.n_embd);

nn::func_t(move |xs, train| {

let xs = xs + xs.apply(&ln1).apply_t(&attn, train);

let ys =

xs.apply(&ln2).apply(&lin1).gelu("none").apply(&lin2).dropout(cfg.resid_pdrop, train);

xs + ys

})

}

fn gpt(p: nn::Path, cfg: Config) -> impl ModuleT {

let p = &p.set_group(NO_WEIGHT_DECAY_GROUP);

let tok_emb = nn::embedding(p / "tok_emb", cfg.vocab_size, cfg.n_embd, Default::default());

let pos_emb = p.zeros("pos_emb", &[1, cfg.block_size, cfg.n_embd]);

let ln_f = nn::layer_norm(p / "ln_f", vec![cfg.n_embd], Default::default());

let head = linear_no_bias(p / "head", cfg.n_embd, cfg.vocab_size);

let mut blocks = nn::seq_t();

for block_idx in 0..cfg.n_layer {

blocks = blocks.add(block(&(p / block_idx), cfg));

}

nn::func_t(move |xs, train| {

let (_sz_b, sz_t) = xs.size2().unwrap();

let tok_emb = xs.apply(&tok_emb);

let pos_emb = pos_emb.i((.., ..sz_t, ..));

(tok_emb + pos_emb)

.dropout(cfg.embd_pdrop, train)

.apply_t(&blocks, train)

.apply(&ln_f)

.apply(&head)

})

}

/// Generates some sample string using the GPT model.

fn sample(data: &TextData, gpt: &impl ModuleT, input: Tensor) -> String {

let mut input = input;

let mut result = String::new();

for _index in 0..SAMPLING_LEN {

let logits = input.apply_t(gpt, false).i((0, -1, ..));

let sampled_y = logits.softmax(-1, Kind::Float).multinomial(1, true);

let last_label = i64::try_from(&sampled_y).unwrap();

result.push(data.label_to_char(last_label));

input = Tensor::cat(&[input, sampled_y.view([1, 1])], 1).narrow(1, 1, BLOCK_SIZE);

}

result

}

pub fn main() -> Result<()> {

let device = Device::cuda_if_available();

let mut vs = nn::VarStore::new(device);

let data = TextData::new("data/input.txt")?;

let labels = data.labels();

println!("Dataset loaded, {labels} labels.");

let cfg = Config {

vocab_size: labels,

n_embd: 512,

n_head: 8,

n_layer: 8,

block_size: BLOCK_SIZE,

attn_pdrop: 0.1,

resid_pdrop: 0.1,

embd_pdrop: 0.1,

};

let gpt = gpt(vs.root() / "gpt", cfg);

let args: Vec<_> = std::env::args().collect();

if args.len() < 2 {

bail!("usage: main (train|predict weights.ot seqstart)")

}

match args[1].as_str() {

"train" => {

let mut opt = nn::AdamW::default().build(&vs, LEARNING_RATE)?;

opt.set_weight_decay_group(NO_WEIGHT_DECAY_GROUP, 0.0);

opt.set_weight_decay_group(WEIGHT_DECAY_GROUP, 0.1);

let mut idx = 0;

for epoch in 1..(1 + EPOCHS) {

let mut sum_loss = 0.;

let mut cnt_loss = 0.;

for batch in data.iter_shuffle(BLOCK_SIZE + 1, BATCH_SIZE) {

let xs = batch.narrow(1, 0, BLOCK_SIZE).to_kind(Kind::Int64).to_device(device);

let ys = batch.narrow(1, 1, BLOCK_SIZE).to_kind(Kind::Int64).to_device(device);

let logits = xs.apply_t(&gpt, true);

let loss = logits

.view([BATCH_SIZE * BLOCK_SIZE, labels])

.cross_entropy_for_logits(&ys.view([BATCH_SIZE * BLOCK_SIZE]));

opt.backward_step_clip(&loss, 0.5);

sum_loss += f64::try_from(loss)?;

cnt_loss += 1.0;

idx += 1;

if idx % 10000 == 0 {

println!("Epoch: {} loss: {:5.3}", epoch, sum_loss / cnt_loss);

let input = Tensor::zeros([1, BLOCK_SIZE], (Kind::Int64, device));

println!("Sample: {}", sample(&data, &gpt, input));

if let Err(err) = vs.save(format!("gpt{idx}.ot")) {

println!("error while saving {err}");

}

sum_loss = 0.;

cnt_loss = 0.;

}

}

}

}

"predict" => {

vs.load(args[2].as_str())?;

let seqstart = args[3].as_str();

let input = Tensor::zeros([1, BLOCK_SIZE], (Kind::Int64, device));

for (idx, c) in seqstart.chars().rev().enumerate() {

let idx = idx as i64;

if idx >= BLOCK_SIZE {

break;

}

let _filled =

input.i((0, BLOCK_SIZE - 1 - idx)).fill_(data.char_to_label(c)? as i64);

}

println!("Sample: {}", sample(&data, &gpt, input));

}

_ => bail!("usage: main (train|predict weights.ot seqstart)"),

};

Ok(())

}

The code defines a generative model architecture with configurable hyperparameters such as vocabulary size, embedding size, and number of attention heads. It builds a GPT-like model with multiple attention layers that learn to attend to specific positions in the input sequence. The main training loop updates the model using the AdamW optimizer, calculating the loss using cross-entropy based on the model's predicted next character versus the actual character in the sequence. The sample function generates text by sampling from the output probabilities, using a causal mask to ensure that each position only attends to previous positions in the sequence. This mask is crucial for generating text in an autoregressive manner. The predict functionality loads a pre-trained model and takes an input sequence to generate new text, demonstrating the model's learned ability to continue a text sequence in a coherent manner.

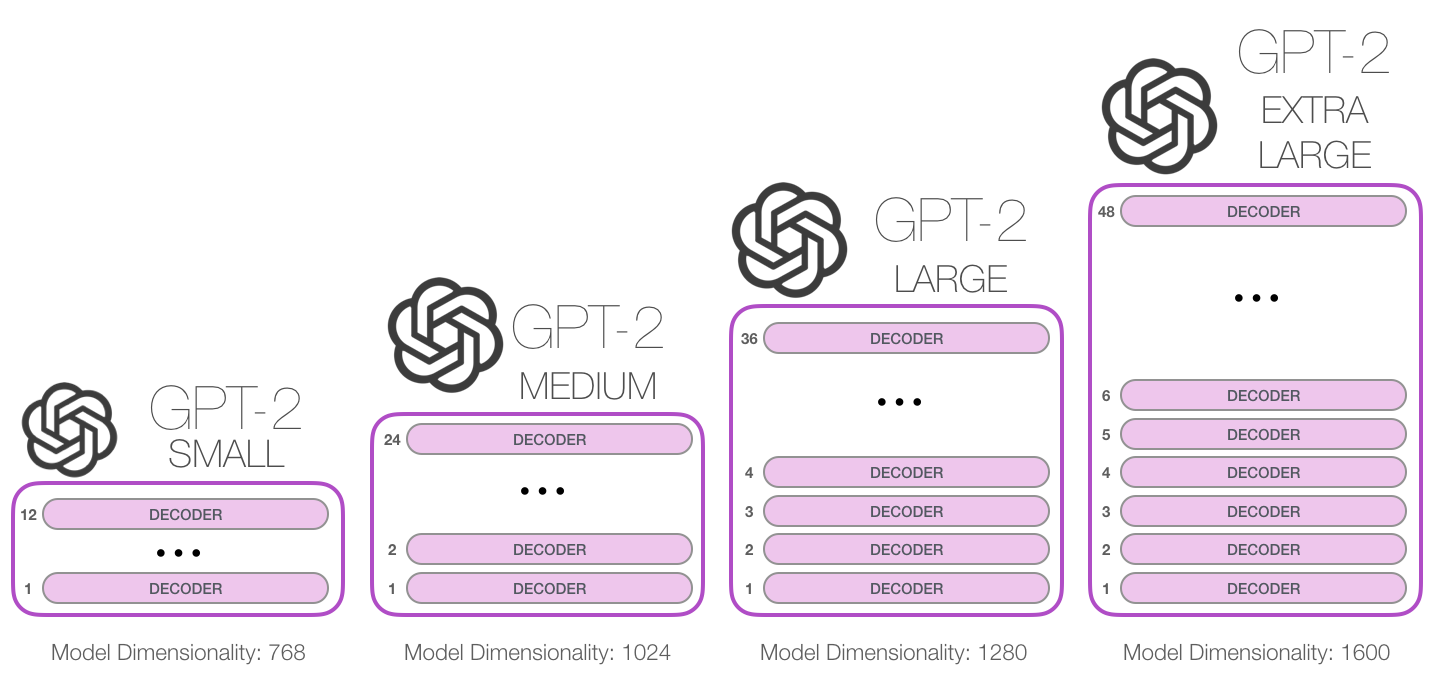

Figure 4: Growth of transformer blocks in various GPT-2 models.

In recent years, industry applications of GPT models have proliferated, especially in areas like customer service, where GPT-powered chatbots can provide automated, contextually relevant responses to user queries. Companies are also using GPT for creative applications, such as content generation and copywriting, where the model can assist in drafting articles, advertisements, or product descriptions. In research, GPT models have been employed to aid in summarizing scientific literature or generating code snippets, demonstrating their versatility across different domains.

As of the latest trends, the development of GPT-4 and similar models with even larger parameter counts has pushed the boundaries of what is possible with generative models. These models can generate highly coherent and contextually nuanced text across a wide range of domains. However, with their growing size, concerns about the computational cost, environmental impact, and ethical considerations, such as biases in generated content, have also become more pronounced. The future of generative models like GPT will likely focus on improving efficiency, interpretability, and control, while exploring new applications that push the limits of machine-generated text.

6.3. GPT Variants and Extensions

As we explore the landscape of generative models, particularly focusing on GPT variants like GPT-2, GPT-3, and their successors, it becomes evident that scaling model architecture and training data has been a central factor in their success. Each GPT variant builds on the foundational Transformer architecture but differs significantly in terms of model size, computational complexity, and the amount of training data involved. GPT-2, for instance, marked a significant jump from GPT, increasing the number of parameters to 1.5 billion from the original GPT’s 110 million. This architectural expansion allowed the model to capture more intricate patterns in the data, enabling it to generate longer and more contextually accurate text. GPT-3, with 175 billion parameters, represents another leap forward, allowing it to engage in few-shot learning and demonstrating remarkable performance across a range of tasks with minimal task-specific data.

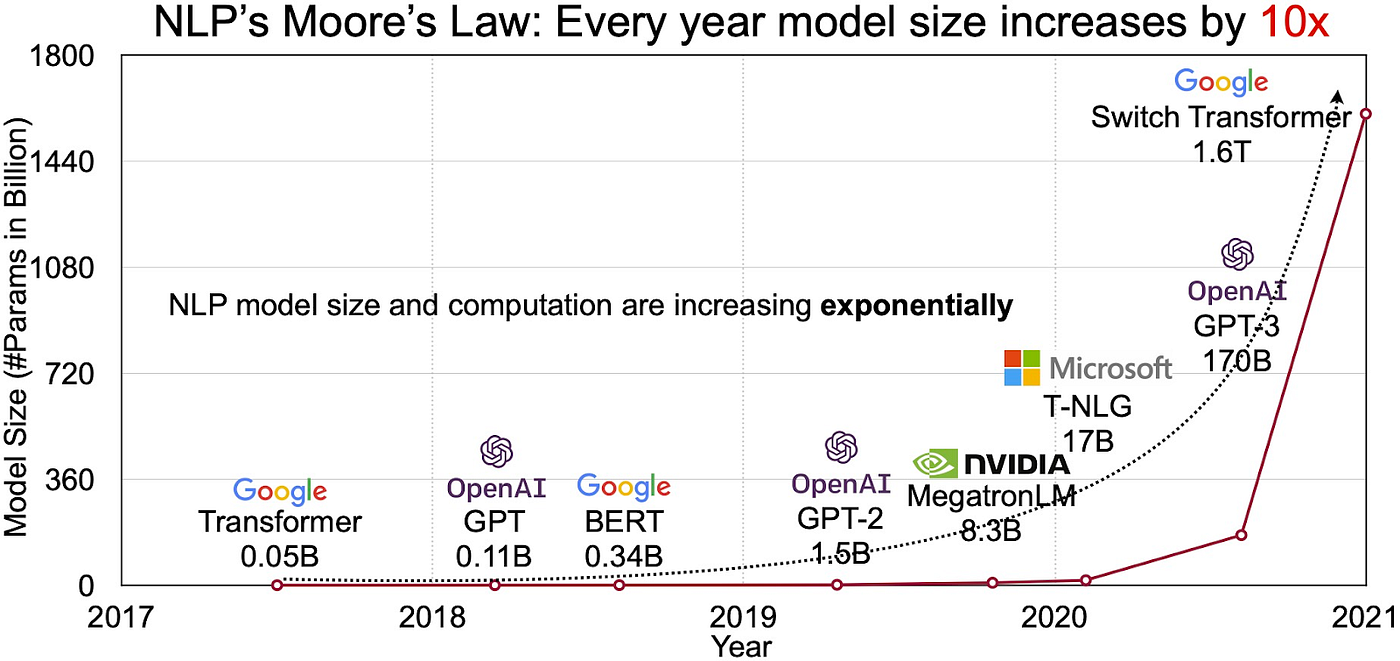

This scaling of model parameters aligns with the exponential "More's Law" observed in natural language processing (NLP), where every major iteration in model development introduces an exponential increase in parameters and capabilities. The term, loosely inspired by Moore’s Law in computing, captures the trend in NLP where the number of parameters in generative models doubles (or more) with each generation. This exponential growth has enabled models to handle increasingly complex tasks, from nuanced text generation to advanced problem-solving across diverse domains. Larger models like GPT-4 continue this trajectory, with scaling not only expanding a model's linguistic capabilities but also enhancing its ability to generalize with fewer examples. This rapid increase in model complexity, coupled with advances in computational power and optimized training techniques, has fueled the continuous advancement of generative AI, shaping the future of human-AI interactions across industries.

Figure 5: The NLP’s Moore’s law.

The differences in architecture across these GPT variants lie primarily in the number of layers, attention heads, and model dimensions. GPT-2 and GPT-3 both maintain the autoregressive architecture, where the model predicts the next token in a sequence based on the previously generated tokens. However, the scale of GPT-3’s architecture allows it to better capture the context and dependencies between words, leading to more coherent and diverse text generation. Additionally, the training data size for these models has grown proportionally with the architecture. GPT-2 was trained on 40 GB of text data, whereas GPT-3 was trained on 570 GB of text, further enhancing its ability to generalize across domains.

Figure 6: Model size comparison of GPT variants.

The concept of scaling laws plays a crucial role in understanding why larger models like GPT-3 perform significantly better than their smaller counterparts. Scaling laws describe how performance improves as model size, dataset size, and computational power increase. Formally, scaling laws can be expressed as:

$$L(N, D, C) = aN^{-\alpha} + bD^{-\beta} + cC^{-\gamma},$$

where $L$ is the loss function, $N$ represents the number of parameters, $D$ is the dataset size, $C$ is the computation (such as training steps), and $a, b, c$, and the exponents $\alpha, \beta, \gamma$ are empirically determined constants. These scaling laws imply that increasing the model size $N$, training data $D$, and computation $C$ leads to predictable reductions in model loss. For models like GPT-3, this means that expanding the number of parameters significantly improves performance across various tasks. However, this improvement comes at an exponentially increasing computational cost.

With this scaling comes practical trade-offs. As models grow, so do their demands on computational resources. Training a model like GPT-3 requires access to high-performance GPUs or TPUs and substantial memory bandwidth. While the larger models yield better performance, they require distributed computing environments to handle their size and complexity, leading to a significant rise in training costs and energy consumption. From an industry perspective, the deployment of such large models, even for inference tasks, can be prohibitively expensive, particularly when scaled across millions of users. Therefore, there is an active trade-off between model size, computational cost, and performance, with researchers constantly seeking ways to optimize this balance.

The ethical considerations surrounding large-scale generative models like GPT-3 also warrant serious discussion. One of the primary concerns is the propagation of biases present in the training data. Since GPT models are trained on large datasets sourced from the internet, they inevitably absorb and replicate biases found in that data. These biases can manifest in harmful ways, such as reinforcing stereotypes, generating offensive content, or perpetuating misinformation. Additionally, the ability of models like GPT-3 to generate highly plausible but factually incorrect content poses risks in terms of disinformation, particularly in areas like automated content generation, where the output may not be easily verifiable by users.

Another concern is the environmental impact of training and deploying such large models. GPT-3’s training process is estimated to have required millions of dollars' worth of computational resources, contributing significantly to energy consumption and carbon emissions. This has led to increasing interest in developing more energy-efficient architectures and training techniques that reduce the environmental footprint of large language models.

Implementing advanced GPT model features, such as those found in GPT-2 and GPT-3, in Rust is an intriguing challenge that leverages the language’s strengths in performance and memory safety. Rust, with its low-level control and concurrency model, is well-suited to handle the demands of large-scale models. Through the tch-rs crate, which interfaces with PyTorch, developers can recreate Transformer-based architectures and apply optimizations tailored for scaling up. These enhancements include expanding attention heads, increasing feed-forward layer sizes, and employing layer normalization to maintain training stability. Rust’s support for parallel processing is also essential for distributing model computations across multiple GPUs or CPUs, making it a strong candidate for deep learning applications.

This Rust code demonstrates how to set up and use OpenAI’s GPT-2 model for text generation using the rust-bert library, a versatile interface for NLP models. By accessing pretrained resources hosted on Hugging Face, the code initializes and configures the GPT-2 model, enabling users to generate coherent text based on input prompts. This example highlights Rust’s growing role in deep learning, showcasing its potential for text generation applications with advantages in speed and memory efficiency, making it a practical choice for handling complex models.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0.90"

rust-bert = "0.19.0"

use rust_bert::pipelines::text_generation::{TextGenerationConfig, TextGenerationModel};

use rust_bert::resources::RemoteResource;

use std::error::Error;

fn main() -> Result<(), Box<dyn Error>> {

// Set up the model resources with correct URLs

let config_resource = RemoteResource::from_pretrained((

"config",

"https://huggingface.co/gpt2/resolve/main/config.json",

));

let vocab_resource = RemoteResource::from_pretrained((

"vocab",

"https://huggingface.co/gpt2/resolve/main/vocab.json",

));

let merges_resource = RemoteResource::from_pretrained((

"merges",

"https://huggingface.co/gpt2/resolve/main/merges.txt",

));

let model_resource = RemoteResource::from_pretrained((

"model",

"https://huggingface.co/gpt2/resolve/main/rust_model.ot",

));

// Configure the text generation model

let generate_config = TextGenerationConfig {

model_resource: Box::new(model_resource),

config_resource: Box::new(config_resource),

vocab_resource: Box::new(vocab_resource),

merges_resource: Box::new(merges_resource),

max_length: 30, // Set the maximum length of generated text

do_sample: true,

temperature: 1.1,

..Default::default()

};

// Load the GPT-2 model

let model = TextGenerationModel::new(generate_config)?;

// Input prompt

let prompt = "Once upon a time";

// Generate text

let output = model.generate(&[prompt], None);

for sentence in output {

println!("{}", sentence);

}

Ok(())

}

The code begins by specifying four resources (model configuration, vocabulary, merge rules, and model weights) for GPT-2, each loaded from a remote Hugging Face repository using RemoteResource. These resources are wrapped in Box::new to meet the type requirements of TextGenerationConfig, which is configured with specific generation parameters, including maximum output length, sampling behavior, and temperature. Once the model is initialized, a prompt is provided, and the generate method is invoked to create a continuation of the input text. The generated text is then printed, with the model outputting a response based on the input prompt. This setup allows for efficient loading and inference of the GPT-2 model within a Rust environment.

One practical approach is to compare the performance of GPT, GPT-2, and GPT-3 on the same NLP task in Rust. This can be done by implementing a simplified version of these models, training them on a common dataset, and benchmarking their performance using metrics such as perplexity, fluency, and response coherence. The differences in model size and architecture will become evident through these comparisons, as larger models like GPT-3 will likely outperform smaller ones, especially in terms of handling long-range dependencies and generating more coherent text.

This Rust code demonstrates how to load and compare the performance of two different language generation models—GPT-2 and a GPT-3-like model (GPT-Neo)—across various NLP tasks. Utilizing the rust-bert library, the code initializes pretrained language models by accessing model configurations, vocabulary, merge rules, and weight files hosted on Hugging Face. It measures and outputs the time each model takes to generate text, enabling a straightforward comparison of performance between smaller and larger language models in Rust.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0.90"

rust-bert = "0.19.0"

use rust_bert::pipelines::text_generation::{TextGenerationConfig, TextGenerationModel};

use rust_bert::resources::RemoteResource;

use std::error::Error;

use std::time::Instant;

fn main() -> Result<(), Box<dyn Error>> {

// URLs for GPT-2 model resources

let gpt2_resources = (

"https://huggingface.co/gpt2/resolve/main/config.json",

"https://huggingface.co/gpt2/resolve/main/vocab.json",

"https://huggingface.co/gpt2/resolve/main/merges.txt",

"https://huggingface.co/gpt2/resolve/main/rust_model.ot",

);

// URLs for GPT-3-like model resources (e.g., GPT-neo or GPT-J)

let gpt3_resources = (

"https://huggingface.co/EleutherAI/gpt-neo-2.7B/resolve/main/config.json",

"https://huggingface.co/EleutherAI/gpt-neo-2.7B/resolve/main/vocab.json",

"https://huggingface.co/EleutherAI/gpt-neo-2.7B/resolve/main/merges.txt",

"https://huggingface.co/EleutherAI/gpt-neo-2.7B/resolve/main/rust_model.ot",

);

// Load both models

let gpt2_model = load_model(gpt2_resources, "GPT-2")?;

let gpt3_model = load_model(gpt3_resources, "GPT-3")?;

// Test prompts for each NLP task

let prompts = vec![

("text generation", "Once upon a time"),

("question answering", "What is the capital of France?"),

("summarization", "Rust is a systems programming language focused on safety, speed, and concurrency."),

];

// Run models on each task and measure performance

for (task, prompt) in prompts {

println!("\nTask: {}", task);

let gpt2_output = run_model(&gpt2_model, prompt, "GPT-2")?;

let gpt3_output = run_model(&gpt3_model, prompt, "GPT-3")?;

println!("GPT-2 output: {}", gpt2_output);

println!("GPT-3 output: {}", gpt3_output);

}

Ok(())

}

// Function to load a model based on provided URLs and model name

fn load_model(resources: (&str, &str, &str, &str), model_name: &str) -> Result<TextGenerationModel, Box<dyn Error>> {

let (config_url, vocab_url, merges_url, model_url) = resources;

let config_resource = RemoteResource::from_pretrained(("config", config_url));

let vocab_resource = RemoteResource::from_pretrained(("vocab", vocab_url));

let merges_resource = RemoteResource::from_pretrained(("merges", merges_url));

let model_resource = RemoteResource::from_pretrained(("model", model_url));

// Configure the model

let generate_config = TextGenerationConfig {

model_resource: Box::new(model_resource),

config_resource: Box::new(config_resource),

vocab_resource: Box::new(vocab_resource),

merges_resource: Box::new(merges_resource),

max_length: 50,

do_sample: true,

temperature: 1.1,

..Default::default()

};

println!("Loading {} model...", model_name);

let model = TextGenerationModel::new(generate_config)?;

Ok(model)

}

// Function to run a specific model and measure performance

fn run_model(model: &TextGenerationModel, prompt: &str, model_name: &str) -> Result<String, Box<dyn Error>> {

println!("\nRunning {} on prompt: {}", model_name, prompt);

let start_time = Instant::now();

let output = model.generate(&[prompt], None);

let duration = start_time.elapsed();

let generated_text = output.get(0).cloned().unwrap_or_default();

println!("{} took: {:?}", model_name, duration);

Ok(generated_text)

}

The code begins by specifying resource URLs for GPT-2 and GPT-Neo, which act as stand-ins for GPT-2 and GPT-3. These resources, such as configuration files and model weights, are downloaded using RemoteResource::from_pretrained. Two functions, load_model and run_model, handle the loading and execution of each model. load_model creates a TextGenerationModel instance with a specified configuration for each model, while run_model measures the time taken to generate text from each model given a prompt. Finally, for three NLP tasks (text generation, question answering, and summarization), each model generates output for the provided prompt, and the results—including generation times and outputs—are printed for comparison. This setup highlights Rust’s capability in handling deep learning tasks with efficiency.

Managing the computational demands of large GPT models is another significant consideration, especially when implementing them in Rust. Model parallelism is one technique to address this issue. In model parallelism, the parameters of a large model are split across multiple devices, allowing the model to scale beyond the memory limits of a single GPU or CPU. Rust’s memory safety guarantees ensure that these large models can be distributed across devices without risking memory leaks or unsafe memory access, a common concern when working with large-scale computations. Additionally, Rust’s efficient memory management and zero-cost abstractions enable developers to implement optimizations such as mixed precision training, where the model uses lower precision floating-point numbers to reduce memory usage and improve computational efficiency without sacrificing performance.

In industry, advanced GPT variants have been deployed in various applications, from automated customer service chatbots to content generation tools and coding assistants like GitHub Copilot. These models are also being used to automate and streamline workflows in industries such as healthcare, finance, and legal services, where the ability to generate, summarize, and process large volumes of text is highly valuable. GPT-3, in particular, has found widespread use in applications that require natural-sounding, contextually appropriate responses, enabling more sophisticated human-machine interactions.

Looking forward, the latest trends in the development of GPT variants are focused on improving efficiency, reducing the environmental impact, and enhancing the controllability of these models. Researchers are exploring techniques like model distillation, where a smaller model is trained to mimic the behavior of a larger model, effectively compressing the large model’s knowledge into a more manageable size without significant loss in performance. Additionally, hybrid models that combine GPT’s generative capabilities with reinforcement learning techniques are being developed to better align generated content with human values and reduce harmful outputs. These trends indicate a growing recognition of the need to balance the power of large language models with ethical considerations and sustainability.

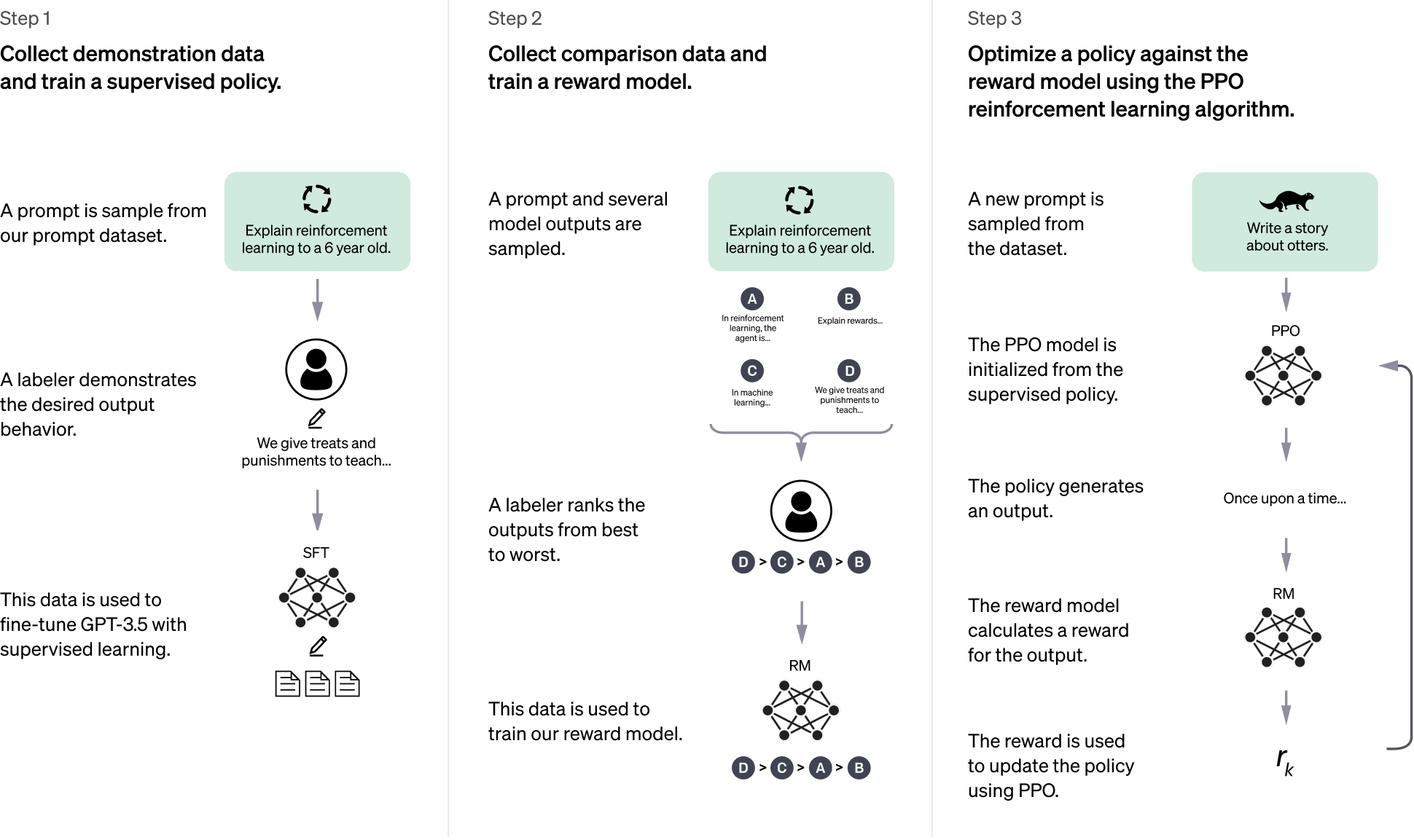

6.4. Training, Fine-Tuning and Task Adaptation of GPT Model

In this section we discuss the detailed methods OpenAI employs for training, fine-tuning, and adapting their GPT models are thoroughly explored, focusing on a structured Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback (RLHF) approach. This process involves three critical stages: Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) with demonstration data, Reward Model training using comparative data, and policy optimization against this reward model using Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO). These stages ensure that the GPT model can produce responses aligned with human preferences while maintaining adaptability across a range of NLP tasks.

Figure 7: How OpenAI train GPT 3.5 model.

The first stage, Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT), establishes a baseline model by training it on high-quality, human-curated data. Each sample contains an input $X$ and an expected output $Y$, allowing the model to learn through labeled examples. This stage optimizes the model's parameters $\theta$ by minimizing the negative log-likelihood loss function, as shown below:

$$ \mathcal{L}_{\text{SFT}}(\theta) = - \sum_{(X, Y) \in \text{Dataset}} \log P_\theta(Y | X) $$

This objective maximizes the likelihood of generating the correct output $Y$ given input $X$, reinforcing the foundational language patterns in the model's responses. In Rust, using the tch-rs crate, this supervised fine-tuning step implementation can be illustrated as follows:

use tch::{nn, Tensor, Device, Kind};

use tch::nn::{Module, OptimizerConfig};

fn supervised_fine_tuning(vs: &nn::Path, input_tensor: Tensor, target_tensor: Tensor) -> Tensor {

let model = nn::seq()

.add(nn::linear(vs / "layer1", 512, 1024, Default::default()))

.add(nn::relu())

.add(nn::linear(vs / "output_layer", 1024, 512, Default::default()));

let optimizer = nn::Adam::default().build(vs, 1e-4).unwrap();

let logits = model.forward(&input_tensor);

let loss = logits.cross_entropy_for_logits(&target_tensor);

optimizer.backward_step(&loss);

loss

}

The second stage, Reward Model Training, refines the model’s understanding of quality by introducing a reward model $R_\phi$, where $\phi$ are the parameters. In this stage, human annotators provide comparative feedback by ranking outputs from the model, which the reward model then uses to learn a scalar reward for each output based on its quality. The reward model's objective function is:

$$\mathcal{L}_{\text{Reward}}(\phi) = \mathbb{E}_{(Y_1, Y_2) \sim D} \left[ \log \sigma\left(R_\phi(Y_1) - R_\phi(Y_2)\right) \right]$$

where $\sigma$ is the sigmoid function, which smooths the difference between scores assigned to preferred and non-preferred outputs. This training ensures that higher rewards are associated with more desirable outputs. A simple Rust implementation of this stage could be as follows:

fn reward_model_training(vs: &nn::Path, y1: Tensor, y2: Tensor) -> Tensor {

let reward_model = nn::seq().add(nn::linear(vs / "reward_layer", 512, 1, Default::default()));

let r_y1 = reward_model.forward(&y1).mean(Kind::Float);

let r_y2 = reward_model.forward(&y2).mean(Kind::Float);

let reward_loss = -(r_y1 - r_y2).sigmoid().log();

reward_loss.backward();

reward_loss

}

The third stage, Policy Optimization using Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), adapts the model’s policy using reinforcement learning against the reward model. PPO is particularly effective for stabilizing the learning process by clipping the probability ratios between the new and old policies, preventing abrupt changes. The PPO objective function is:

$$ \mathcal{L}_{\text{PPO}}(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{(X, Y) \sim D} \left[ \min \left( r_t(\theta) \hat{A}, \text{clip}(r_t(\theta), 1 - \epsilon, 1 + \epsilon) \hat{A} \right) + \beta \, \text{Entropy}(\pi_\theta(Y | X)) \right] $$

where $r_t(\theta) = \frac{\pi_\theta(Y | X)}{\pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}(Y | X)}$ is the probability ratio, $\epsilon$ is a clipping parameter, and $\beta$ is a coefficient that weights the entropy term to encourage exploration. The PPO algorithm maximizes the reward model's output while maintaining stable learning. An example Rust code for PPO updates can be structured as follows:

fn ppo_update(vs: &nn::Path, input_tensor: Tensor, action_tensor: Tensor, old_log_probs: Tensor, advantage: Tensor) -> Tensor {

let policy_model = nn::seq().add(nn::linear(vs / "policy_layer", 512, 1024, Default::default()));

let optimizer = nn::Adam::default().build(vs, 1e-4).unwrap();

let logits = policy_model.forward(&input_tensor);

let new_log_probs = logits.log_softmax(-1, Kind::Float).gather(1, &action_tensor, false);

let ratio = (new_log_probs - old_log_probs).exp();

let clip_range = 0.2;

let clipped_ratio = ratio.clamp(1.0 - clip_range, 1.0 + clip_range);

let ppo_loss = -Tensor::minimum(ratio * &advantage, clipped_ratio * &advantage).mean(Kind::Float);

optimizer.backward_step(&ppo_loss);

ppo_loss

}

Together, these three stages—Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT), Reward Model training, and Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO)—form a comprehensive pipeline designed to fine-tune language models like GPT for producing contextually relevant, high-quality outputs that align with human values and expectations. This approach, known as Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback (RLHF), is crucial for training models to generate responses that not only make logical sense but are also nuanced and user-friendly. By incorporating human feedback into the training loop, RLHF enables models like OpenAI’s GPT-3.5 to adapt dynamically across a diverse array of tasks, such as text generation, summarization, and question-answering, producing outputs that are not only accurate but also aligned with user preferences. This iterative training pipeline allows the model to improve its performance progressively, balancing consistency with flexibility, thereby making it suitable for a broad range of real-world applications.

This code illustrates a simplified training setup for neural networks using the tch crate, a Rust interface for PyTorch. The code includes the foundational stages of a training pipeline: SFT, reward model training, and PPO, each represented as a Rust function that uses basic dummy inputs and a minimal configuration. Supervised fine-tuning serves as the initial training step, where the model learns to make predictions based on labeled data. The reward model training component then teaches the model to evaluate its outputs against a reward signal, guiding it to make choices that yield higher rewards. Finally, the PPO function implements a reinforcement learning approach to optimize the model’s policy, adjusting it toward actions that maximize cumulative rewards. Together, the constants LEARNING_RATE, BLOCK_SIZE, BATCH_SIZE, and EPOCHS determine the model’s training pace and structure, defining parameters like batch size and epochs for each training loop. Although simplified, this code mirrors the architecture of larger-scale RLHF tasks, providing an experimental foundation for training models that learn to prioritize actions aligned with intended outcomes.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0.90"

tch = "0.12.0"

use anyhow::Result;

use tch::data::TextData;

use tch::nn::{ModuleT, OptimizerConfig};

use tch::{nn, Device, Kind, Tensor};

use tch::nn::Optimizer;

const LEARNING_RATE: f64 = 0.0003;

const BLOCK_SIZE: i64 = 128;

const BATCH_SIZE: i64 = 64;

const EPOCHS: i64 = 3;

#[derive(Debug, Copy, Clone)]

struct Config {

vocab_size: i64,

n_embd: i64,

}

// Define gpt function (example)

fn gpt<'a>(path: nn::Path<'a>, config: Config) -> impl ModuleT + 'a {

nn::seq().add(nn::linear(&path / "layer1", config.n_embd, config.vocab_size, Default::default()))

}

// Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT)

fn supervised_fine_tuning(_vs: &nn::Path, data: &TextData, model: &impl ModuleT, opt: &mut Optimizer) -> Result<()> {

for epoch in 1..=EPOCHS {

let mut total_loss = 0.;

for batch in data.iter_shuffle(BLOCK_SIZE + 1, BATCH_SIZE) {

let xs = batch.narrow(1, 0, BLOCK_SIZE)

.to_kind(Kind::Float) // Consistent dtype

.to_device(Device::cuda_if_available());

let ys = batch.narrow(1, 1, BLOCK_SIZE)

.to_kind(Kind::Float) // Consistent dtype

.to_device(Device::cuda_if_available());

let logits = xs.apply_t(model, true);

let loss = logits.view([BATCH_SIZE * BLOCK_SIZE, data.labels() as i64])

.cross_entropy_for_logits(&ys.view([BATCH_SIZE * BLOCK_SIZE]));

opt.backward_step(&loss);

total_loss += f64::try_from(loss)?;

}

println!("SFT Epoch {epoch} - Loss: {}", total_loss);

}

Ok(())

}

// Reward Model Training

fn train_reward_model(vs: &nn::Path, y1: Tensor, y2: Tensor) -> Tensor {

let reward_model = nn::seq().add(nn::linear(vs / "reward_layer", 512, 1, Default::default()));

let r_y1 = reward_model.forward_t(&y1, true).mean(Kind::Float);

let r_y2 = reward_model.forward_t(&y2, true).mean(Kind::Float);

let reward_loss = -(r_y1 - r_y2).sigmoid().log();

reward_loss.backward();

reward_loss

}

// PPO Policy Optimization

fn ppo_update(vs: &nn::VarStore, input: Tensor, action: Tensor, old_log_probs: Tensor, advantage: Tensor) -> Tensor {

let policy_model = nn::seq().add(nn::linear(vs.root() / "policy_layer", 512, 1024, Default::default()));

let mut opt = nn::Adam::default().build(vs, LEARNING_RATE).unwrap();

let logits = policy_model.forward_t(&input, true);

let new_log_probs = logits.log_softmax(-1, Kind::Float).gather(1, &action, false);

let ratio = (new_log_probs - old_log_probs).exp();

let clip_range = 0.2;

let clipped_ratio = ratio.clamp(1.0 - clip_range, 1.0 + clip_range);

let ppo_loss = -Tensor::minimum(&(ratio * &advantage), &(clipped_ratio * &advantage)).mean(Kind::Float);

opt.backward_step(&ppo_loss);

ppo_loss

}

fn main() -> Result<()> {

let device = Device::cuda_if_available();

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(device);

let data = TextData::new("data/input.txt")?;

let cfg = Config {

vocab_size: data.labels() as i64,

n_embd: 512,

};

let model = gpt(vs.root() / "gpt", cfg);

let mut opt = nn::Adam::default().build(&vs, LEARNING_RATE)?;

// Supervised Fine-Tuning

supervised_fine_tuning(&vs.root(), &data, &model, &mut opt)?;

// Dummy input for demonstration

let y1 = Tensor::randn(&[BATCH_SIZE, 512], (Kind::Float, device));

let y2 = Tensor::randn(&[BATCH_SIZE, 512], (Kind::Float, device));

// Reward Model Training

let reward_loss = train_reward_model(&vs.root(), y1, y2);

println!("Reward Model Loss: {:?}", reward_loss);

// PPO Update (dummy values)

let input = Tensor::randn(&[BATCH_SIZE, BLOCK_SIZE, 512], (Kind::Float, device));

let action = Tensor::randint(0, 512, (Kind::Int64, device)); // Adjusted dtype for actions

let old_log_probs = Tensor::randn(&[BATCH_SIZE, 1], (Kind::Float, device));

let advantage = Tensor::randn(&[BATCH_SIZE, 1], (Kind::Float, device));

let ppo_loss = ppo_update(&vs, input, action, old_log_probs, advantage);

println!("PPO Loss: {:?}", ppo_loss);

Ok(())

}

The code initializes a model (gpt) using a basic linear layer as a placeholder for an actual neural network, setting up a training pipeline that includes supervised fine-tuning, reward-based training, and Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO). In the supervised_fine_tuning function, the model undergoes supervised learning, where it is trained to predict labels based on input data. The train_reward_model function then calculates rewards by evaluating the model's predictions, guiding it to prioritize actions that yield higher rewards. Finally, ppo_update implements the PPO algorithm, adjusting model weights through a policy gradient approach that balances exploration and exploitation—key for reinforcement learning tasks. Each function is optimized using tch's GPU capabilities, highlighting Rust's ability to handle complex machine learning workflows with efficiency and safety.

In Rust, adapting and customizing large language models like GPT-3.5 does not require training from scratch. Instead, we can download or purchase pretrained models and then perform fine-tuning to suit specific needs. This process, similar to techniques used by OpenAI, follows a structured workflow: first, obtaining a pretrained model and fine-tuning it on labeled data to adapt its outputs to the target task. This initial fine-tuning can then be enhanced through reinforcement learning techniques such as Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), which refines the model’s policy to produce high-quality, contextually relevant outputs aligned with specific goals. Libraries like rust-bert and tch-rs support this deep learning adaptation in Rust, combining high performance and memory safety to extend the capabilities of large language models across specialized tasks and domains.

The first step is downloading and loading the model into Rust. Although GPT-3.5 is not directly available through the Hugging Face API, we can work with pretrained models like GPT-2 as placeholders to set up a similar pipeline. The model’s configuration, vocabulary, merges, and weights are loaded as resources, and a configuration for generation is set. The model’s configuration object includes parameters like max_length, temperature, and do_sample, allowing the model to generate coherent and contextually relevant outputs based on input prompts.

use rust_bert::gpt2::{GPT2Generator};

use rust_bert::pipelines::generation_utils::{GenerateConfig, LanguageGenerator};

use rust_bert::resources::RemoteResource;

use std::error::Error;

fn download_gpt3_5() -> Result<GPT2Generator, Box<dyn Error>> {

let config = RemoteResource::from_pretrained((

"config",

"https://huggingface.co/gpt2/resolve/main/config.json",

));

let vocab = RemoteResource::from_pretrained((

"vocab",

"https://huggingface.co/gpt2/resolve/main/vocab.json",

));

let merges = RemoteResource::from_pretrained((

"merges",

"https://huggingface.co/gpt2/resolve/main/merges.txt",

));

let weights = RemoteResource::from_pretrained((

"weights",

"https://huggingface.co/gpt2/resolve/main/pytorch_model.bin",

));

let generate_config = GenerateConfig {

model_resource: Box::new(weights),

config_resource: Box::new(config),

vocab_resource: Box::new(vocab),

merges_resource: Box::new(merges),

max_length: 1024,

do_sample: true,

temperature: 1.0,

..Default::default()

};

let generator = GPT2Generator::new(generate_config)?;

Ok(generator)

}

fn main() -> Result<(), Box<dyn Error>> {

let generator = download_gpt3_5()?;

let prompt = "Rust is an amazing programming language because";

let output = generator.generate(Some(&[prompt]), None);

println!("{:?}", output);

Ok(())

}

The code begins by defining a function, download_gpt3_5, which sets up resources required for GPT-2, including model weights, configuration, vocabulary, and merges, all hosted on Hugging Face's model repository. Using RemoteResource, the code downloads these assets and then applies them in GenerateConfig, a structure that defines how the model will generate outputs (e.g., maximum token length, sampling behavior). The model is initialized as a GPT2Generator with this configuration. In main, a sample prompt is passed to the generator, which outputs a continuation based on the prompt by using the generate function. This setup highlights the utility of pretrained models in Rust, allowing developers to generate contextually appropriate language outputs by combining pretrained weights with fine-tuning configurations.

After successfully downloading the model, the next step involves fine-tuning. Fine-tuning adjusts the model’s parameters to adapt it to a specific task, where we minimize the supervised loss $L(\theta) = -\sum_{(X, Y) \in D} \log P_\theta(Y \mid X)$, with $\theta$ representing model parameters, $X$ as the input text, and $Y$ as the desired output. This adjustment process requires high-quality labeled data pairs and a structured objective function that aligns the model’s outputs with desired responses, setting the stage for further optimization.

use tch::{nn, Device, Kind, Tensor};

use tch::nn::{Module, OptimizerConfig};

use rust_bert::pipelines::generation::{GPT2Generator};

fn fine_tune_gpt3_5(generator: &GPT2Generator, data: &[(String, String)]) -> Result<(), Box<dyn Error>> {

let device = Device::cuda_if_available();

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(device);

let config = generator.get_config();

let linear_layer = nn::linear(vs.root(), config.n_embd, config.vocab_size, Default::default());

let optimizer = nn::Adam::default().build(&vs, 1e-4)?;

for (input_text, target_text) in data.iter() {

let input_tensor = generator.encode(input_text.clone())?;

let target_tensor = generator.encode(target_text.clone())?;

let logits = linear_layer.forward(&input_tensor);

let loss = logits.cross_entropy_for_logits(&target_tensor);

optimizer.backward_step(&loss);

println!("Fine-tuning loss: {}", f64::try_from(loss)?);

}

Ok(())

}

Finally, we perform task adaptation through reinforcement learning by using Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO). PPO is designed to stabilize the fine-tuned model by adjusting its policy with respect to a reward model, which evaluates how closely the model aligns with human-preferred outputs. The objective function for PPO can be represented as $L_{PPO}(\theta)$, that optimizes the model’s responses while ensuring stability by constraining updates to a safe range.

fn ppo_update(

policy_model: &impl Module,

input_tensor: Tensor,

action_tensor: Tensor,

old_log_probs: Tensor,

advantage: Tensor,

epsilon: f64,

vs: &nn::Path,

) -> Tensor {

let optimizer = nn::Adam::default().build(vs, 1e-4).unwrap();

let logits = policy_model.forward(&input_tensor);

let new_log_probs = logits.log_softmax(-1, Kind::Float).gather(1, &action_tensor, false);

let ratio = (new_log_probs - old_log_probs).exp();

let clipped_ratio = ratio.clamp(1.0 - epsilon, 1.0 + epsilon);

let ppo_loss = -Tensor::minimum(ratio * &advantage, clipped_ratio * &advantage).mean(Kind::Float);

let entropy_bonus = logits.log_softmax(-1, Kind::Float).exp().entropy();

let total_loss = ppo_loss + 0.01 * entropy_bonus;

optimizer.backward_step(&total_loss);

total_loss

}

By combining these techniques—downloading and loading a pretrained model, fine-tuning with labeled data, and refining with PPO—this pipeline adapts GPT-3.5 for specific tasks, improving the model's relevance and quality. The final outcome is a large language model customized to produce high-quality, contextually appropriate responses aligned with user preferences, all while leveraging Rust's powerful performance and safety features.

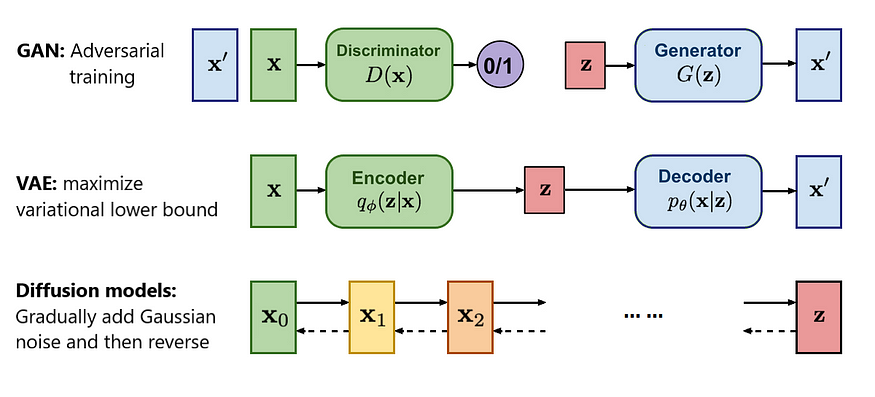

6.5. Advanced Generative Techniques Beyond GPT

In recent years, the field of generative modeling has expanded beyond autoregressive models like GPT, introducing a range of advanced techniques such as Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), and Diffusion Models. These models represent different approaches to generative tasks, and each brings its unique strengths and limitations, especially when applied to domains like image generation, style transfer, and anomaly detection. While GPT models excel in natural language processing through their autoregressive mechanisms, models like VAEs, GANs, and Diffusion Models have proven to be highly effective in other domains, particularly where generating high-resolution and complex data is essential.

Figure 8: Comparison between GAN, VAE and Diffusion models.

Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) are a class of generative models that aim to learn the underlying distribution of data by encoding it into a latent space and then decoding it back into the original form. VAEs introduce a probabilistic framework where the encoder maps the input data into a distribution over latent variables, typically modeled as a Gaussian distribution. The decoder then reconstructs the data from samples drawn from this latent distribution. Mathematically, the VAE optimizes the evidence lower bound (ELBO) as its loss function:

$$\mathcal{L}_{\text{VAE}} = \mathbb{E}_{q(z|x)} \left[ \log p(x|z) \right] - \text{KL}(q(z|x) || p(z)),$$

where $x$ is the input data, $z$ is the latent variable, $p(x|z)$ is the likelihood of reconstructing $x$ given $z$, and the second term is the Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence between the approximate posterior $q(z|x)$ and the prior $p(z)$, which ensures that the learned latent space adheres to a Gaussian distribution. VAEs enable smooth interpolation between data points, which makes them useful for tasks like data compression, anomaly detection, and generating variations of input data. The key advantage of VAEs is their ability to model complex latent spaces, allowing for the generation of new, plausible samples even if the model is trained on relatively small datasets.

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) are another powerful class of generative models that employ adversarial training between two neural networks: the generator and the discriminator. The generator's task is to produce synthetic data that resembles the training data, while the discriminator's role is to distinguish between real data and generated (fake) data. The two networks are trained simultaneously, with the generator trying to fool the discriminator and the discriminator attempting to become better at detecting fake data. The objective function of a GAN can be formulated as a minimax game:

$$\min_G \max_D \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_{\text{data}}(x)} \left[ \log D(x) \right] + \mathbb{E}_{z \sim p_z(z)} \left[ \log (1 - D(G(z))) \right],$$

where $G(z)$ represents the generator's output, which is derived from random noise $z$, and $D(x)$ is the discriminator's probability estimate that input $x$ is real. The adversarial nature of GANs often leads to highly realistic outputs, especially in image generation tasks. GANs are widely used for tasks like high-resolution image synthesis, style transfer, and even generating synthetic medical data for research. However, training GANs can be notoriously difficult due to issues like mode collapse, where the generator learns to produce a limited variety of outputs, and instability in the adversarial training process.

Diffusion Models are a more recent development in generative modeling and have gained attention for their ability to generate high-quality, high-resolution data across various modalities, including images, audio, and even 3D shapes. Diffusion models work by iteratively corrupting the data (such as adding noise) and then learning a reverse process that can recover the original data. Mathematically, diffusion models are trained to minimize the difference between the data distribution and the distribution obtained by gradually adding Gaussian noise. The reverse process, modeled as a Markov chain, is used to sample from the noisy distribution back to the original data distribution. The loss function typically involves the reconstruction of data from noisy samples at various levels of degradation:

$$\mathcal{L}_{\text{diffusion}} = \mathbb{E}_{q} \left[ \| x_t - x \|^2 \right],$$

where $x_t$ is the noisy sample at time step $t$, and the model learns to reconstruct the original data $x$ from these noisy versions. Diffusion models have shown impressive results in generating highly detailed images and other forms of data, often outperforming GANs in terms of diversity and fidelity. This is largely due to their more stable training process, which avoids some of the issues found in GANs, such as mode collapse and convergence difficulties.

In practice, implementing a VAE or GAN in Rust involves building the encoder-decoder architecture for VAEs or the generator-discriminator pair for GANs. Using the tch-rs crate, developers can easily implement these models in Rust, leveraging the performance advantages of the language while maintaining compatibility with PyTorch. For a VAE, the encoder network maps the input data to a mean and variance vector, from which latent variables are sampled, while the decoder reconstructs the data from these latent variables. For a GAN, the generator network takes random noise as input and attempts to produce data samples indistinguishable from the real data, while the discriminator tries to classify samples as real or fake.

The Relativistic GAN (RGAN) model extends traditional Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) by adjusting the discriminator to predict not just whether an image is real or fake but also its realism relative to other generated images. This approach allows the model to capture more nuanced characteristics of real images, improving the quality of generated images. The code here implements a Relativistic Deep Convolutional GAN (DCGAN) using the tch library in Rust, aiming to generate realistic images from latent noise input. This implementation sets up a training loop where a generator learns to create increasingly realistic images, while a discriminator learns to differentiate these from real images. Together, these components create a feedback loop where each model improves based on the other’s outputs.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0.90"

tch = "0.12.0"

// Realtivistic DCGAN.

// https://github.com/AlexiaJM/RelativisticGAN

//

// TODO: override the initializations if this does not converge well.

use anyhow::{bail, Result};

use tch::{kind, nn, nn::OptimizerConfig, Device, Kind, Tensor};

const IMG_SIZE: i64 = 64;

const LATENT_DIM: i64 = 128;

const BATCH_SIZE: i64 = 32;

const LEARNING_RATE: f64 = 1e-4;

const BATCHES: i64 = 100000000;

fn tr2d(p: nn::Path, c_in: i64, c_out: i64, padding: i64, stride: i64) -> nn::ConvTranspose2D {

let cfg = nn::ConvTransposeConfig { stride, padding, bias: false, ..Default::default() };

nn::conv_transpose2d(p, c_in, c_out, 4, cfg)

}

fn conv2d(p: nn::Path, c_in: i64, c_out: i64, padding: i64, stride: i64) -> nn::Conv2D {

let cfg = nn::ConvConfig { stride, padding, bias: false, ..Default::default() };

nn::conv2d(p, c_in, c_out, 4, cfg)

}

fn generator(p: nn::Path) -> impl nn::ModuleT {

nn::seq_t()

.add(tr2d(&p / "tr1", LATENT_DIM, 1024, 0, 1))

.add(nn::batch_norm2d(&p / "bn1", 1024, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|xs| xs.relu())

.add(tr2d(&p / "tr2", 1024, 512, 1, 2))

.add(nn::batch_norm2d(&p / "bn2", 512, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|xs| xs.relu())

.add(tr2d(&p / "tr3", 512, 256, 1, 2))

.add(nn::batch_norm2d(&p / "bn3", 256, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|xs| xs.relu())

.add(tr2d(&p / "tr4", 256, 128, 1, 2))

.add(nn::batch_norm2d(&p / "bn4", 128, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|xs| xs.relu())

.add(tr2d(&p / "tr5", 128, 3, 1, 2))

.add_fn(|xs| xs.tanh())

}

fn leaky_relu(xs: &Tensor) -> Tensor {

xs.maximum(&(xs * 0.2))

}

fn discriminator(p: nn::Path) -> impl nn::ModuleT {

nn::seq_t()

.add(conv2d(&p / "conv1", 3, 128, 1, 2))

.add_fn(leaky_relu)

.add(conv2d(&p / "conv2", 128, 256, 1, 2))

.add(nn::batch_norm2d(&p / "bn2", 256, Default::default()))

.add_fn(leaky_relu)

.add(conv2d(&p / "conv3", 256, 512, 1, 2))

.add(nn::batch_norm2d(&p / "bn3", 512, Default::default()))

.add_fn(leaky_relu)

.add(conv2d(&p / "conv4", 512, 1024, 1, 2))

.add(nn::batch_norm2d(&p / "bn4", 1024, Default::default()))

.add_fn(leaky_relu)

.add(conv2d(&p / "conv5", 1024, 1, 0, 1))

}

fn mse_loss(x: &Tensor, y: &Tensor) -> Tensor {

let diff = x - y;

(&diff * &diff).mean(Kind::Float)

}

// Generate a 2D matrix of images from a tensor with multiple images.

fn image_matrix(imgs: &Tensor, sz: i64) -> Result<Tensor> {

let imgs = ((imgs + 1.) * 127.5).clamp(0., 255.).to_kind(Kind::Uint8);

let mut ys: Vec<Tensor> = vec![];

for i in 0..sz {

ys.push(Tensor::cat(&(0..sz).map(|j| imgs.narrow(0, 4 * i + j, 1)).collect::<Vec<_>>(), 2))

}

Ok(Tensor::cat(&ys, 3).squeeze_dim(0))

}

pub fn main() -> Result<()> {

let device = Device::cuda_if_available();

let args: Vec<_> = std::env::args().collect();