Chapter 5

‘Bidirectional Models: BERT and Its Variants’

"Attention is all you need. The Transformer architecture has fundamentally changed how we think about sequence modeling, enabling us to handle complex language tasks with unprecedented efficiency and accuracy." — Ashish Vaswani

Chapter 4 of LMVR provides an in-depth exploration of the Transformer architecture, a groundbreaking model that revolutionized natural language processing by enabling efficient parallel processing and capturing long-range dependencies in text. The chapter covers essential components such as self-attention, multi-head attention, and positional encoding, explaining how these elements work together to enhance the model's ability to understand and generate language. It also delves into the encoder-decoder structure, layer normalization, and residual connections, highlighting their roles in stabilizing and optimizing the model. Practical aspects of implementing and fine-tuning Transformer models in Rust are also addressed, offering readers the tools to apply these concepts to real-world NLP tasks effectively.

5.1. Introduction to Bidirectional Models

In natural language processing (NLP), bidirectional models like BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) have revolutionized the way machines understand language by capturing context from both directions of a sentence. Traditionally, many language models, such as GPT (Generative Pretrained Transformer), are unidirectional, meaning they generate or predict words based on the preceding context alone. This limitation makes it difficult for unidirectional models to fully grasp the meaning of words that depend on future context in the sentence. For instance, in the sentence "The bank approved the loan," the word "bank" could refer to a financial institution or a riverbank, and understanding the context of "approved the loan" (future context) is crucial to interpreting "bank" correctly.

Bidirectional models like BERT address this issue by considering both left-to-right and right-to-left contexts simultaneously. In BERT, for example, the model learns to predict masked words by using information from both sides of the target word. Formally, for a given sentence $S = [x_1, x_2, ..., x_n]$, a bidirectional model computes a representation for each word $x_i$ by attending to the entire sentence $S$, thus considering information from both $x_1$ through $x_{i-1}$ (preceding context) and $x_{i+1}$ through $x_n$ (succeeding context). This design allows BERT to capture bidirectional dependencies in language, which is critical for many downstream tasks such as question answering and sentiment analysis, where understanding the full context is essential for accurate interpretation.

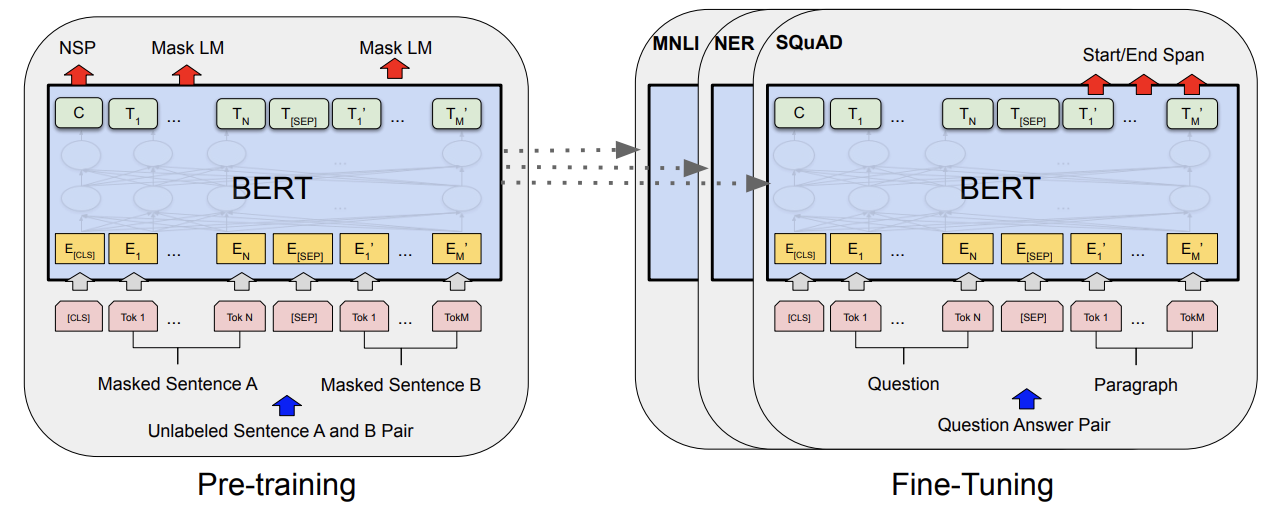

Figure 1: Overall pre-training and fine-tuning procedures for BERT (Ref: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1810.04805).

BERT can be fine-tuned for tasks like MNLI (Multi-Genre Natural Language Inference), NER (Named Entity Recognition), and SQuAD (Stanford Question Answering Dataset) by leveraging its bidirectional nature, which allows it to capture context from both preceding and succeeding words in a sentence. For MNLI, BERT is fine-tuned to understand relationships between sentence pairs by attending to both sentences simultaneously, helping it determine whether one sentence entails, contradicts, or is neutral to another. In NER, BERT uses bidirectional context to accurately label named entities within a sentence (e.g., names, locations), ensuring that the model considers both the word itself and surrounding words to make correct predictions. For SQuAD, BERT is fine-tuned to answer questions by predicting start and end tokens in a passage that best match the given query, using its ability to attend to both the query and the passage context at the same time. This bidirectional approach allows BERT to excel in these tasks by understanding full sentence-level context, crucial for tasks that require precise interpretation of language dependencies.

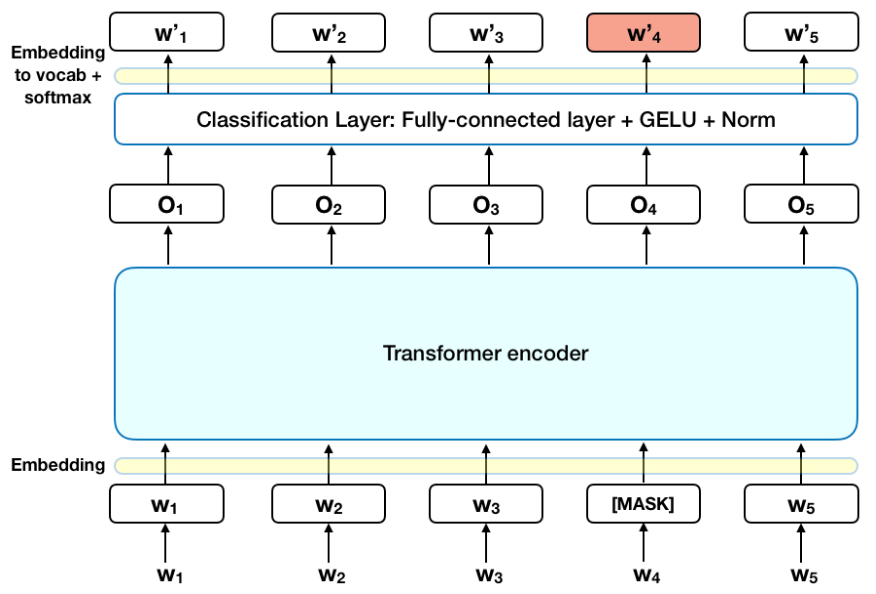

Mathematically, this process is often achieved using masked language modeling (MLM), where a portion of the input tokens is masked, and the model is trained to predict the masked tokens using the surrounding context. For a masked token $x_m$, the objective is to maximize the probability $P(x_m | x_1, ..., x_{m-1}, x_{m+1}, ..., x_n)$, leveraging information from both directions. This is in contrast to unidirectional models, which typically optimize an autoregressive objective that predicts the next word based on previous ones, i.e., $P(x_m | x_1, ..., x_{m-1})$.

Context in Natural Language Understanding is fundamental to most NLP tasks. Consider tasks like question answering, where the model must comprehend the context of a question and extract relevant information from a passage. For example, in the question, "What year did the company go public?" the model needs to consider both the question and the passage to extract the right year. Bidirectional models, like BERT, enable a richer understanding by attending to the whole input, making them superior in tasks that rely on full-sentence comprehension. Similarly, in sentiment analysis, the sentiment of a word can depend on the entire sentence context. For instance, the phrase "not bad" expresses a positive sentiment, even though the word "bad" alone might have a negative connotation. A bidirectional model can capture these nuances effectively.

The development of BERT and its bidirectional approach was motivated by the limitations of unidirectional models, especially in capturing long-range dependencies within text. Unidirectional models, like GPT, rely on autoregression, predicting tokens sequentially from left to right. While this works well for generative tasks like text generation, it does not fully capture the relationships between words that require understanding the entire sequence at once. Bidirectional models solve this by processing sentences holistically, improving performance on a wide range of natural language understanding (NLU) tasks, such as named entity recognition (NER), sentence classification, and paraphrase detection.

The flow of information in bidirectional models like BERT contrasts with autoregressive models such as GPT. In GPT, each token in the sequence depends only on the preceding tokens, making the model effective for text generation but less suitable for tasks where the meaning of a word depends on both prior and future words. Bidirectional models, on the other hand, use self-attention mechanisms that allow each token to attend to every other token in the sequence, thus learning relationships and dependencies across the entire sentence. This difference is particularly important in question answering tasks where bidirectional models outperform autoregressive models by leveraging context from the entire passage to pinpoint the correct answer.

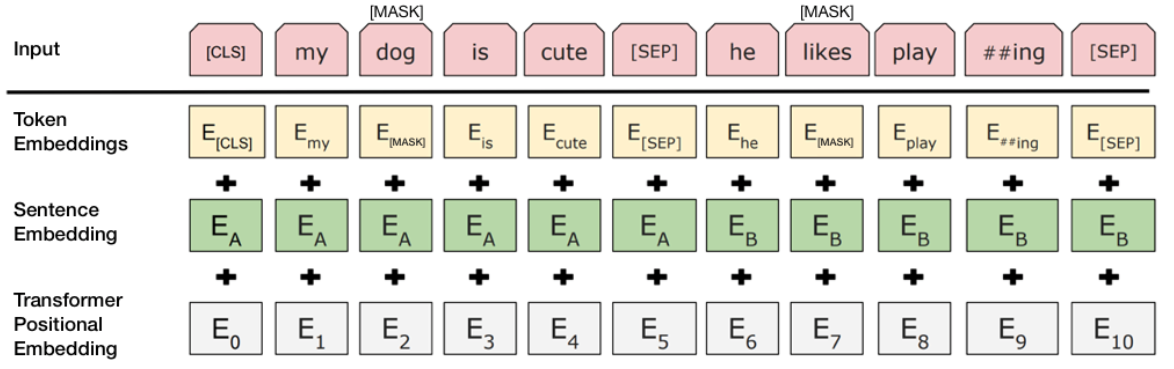

Before discussing detail implementation of the BERT model, lets start with the input layer. The input layer of BERT consists of three key embeddings: token embedding, positional embedding, and segment (or sentence) embedding. The token embedding is responsible for converting each token (word or subword) in a sentence into a dense vector representation. BERT uses a WordPiece tokenizer that breaks down words into subwords or characters to handle rare words. The positional embedding encodes the position of each token in the sequence, ensuring that the model is aware of the order of the tokens since BERT processes tokens in parallel, unlike recurrent models. This positional information is added to each token’s embedding, allowing BERT to capture the sequential nature of language. Finally, the segment embedding helps BERT differentiate between tokens from different sentences in tasks where pairs of sentences are involved (such as next sentence prediction). For each token, its corresponding embeddings from the token, positional, and segment layers are summed to form a complete input representation, which is then fed into the transformer layers for further processing. This combination allows BERT to understand the content, order, and sentence structure in the input.

Figure 2: Illustration of input layer of BERT model.

The classification layer takes the final pooled representation (which aggregates information across all tokens in the sequence) and transforms it into logits for binary classification. The model is trained using cross-entropy loss, a common loss function for classification tasks, and the parameters are updated using the Adam optimizer. In this demonstration, random tensors are used to simulate input data, but in practice, a preprocessed dataset such as IMDB (for sentiment analysis) would be used. The IMDB dataset would require tokenization using a tool like BERTTokenizer (commonly found in Python libraries) to convert raw text into numerical token sequences that the model can process. After preprocessing, the dataset would be loaded into Rust as input and target tensors, and the model would be trained on this real data.

Benchmarking bidirectional models like BERT against unidirectional models like GPT highlights the strengths of bidirectionality in tasks requiring comprehensive understanding of context. In sentiment analysis, for instance, a bidirectional model captures the sentiment of a sentence more effectively because it processes the entire sentence at once, considering both preceding and succeeding words. In contrast, a unidirectional model (like GPT) processes text sequentially and might miss key context if crucial information appears later in the sentence. In tasks such as question answering, BERT’s bidirectional attention mechanism enables it to attend simultaneously to both the question and the relevant parts of the passage, yielding more accurate and precise answers.

However, training bidirectional models introduces computational challenges. Bidirectional models process entire sequences at once, which requires more memory and computational resources than unidirectional models. Moreover, BERT’s masked language modeling (MLM) objective, which involves predicting masked tokens based on surrounding context, slows down training compared to autoregressive models like GPT, which predict one token at a time. Despite these challenges, bidirectional models like BERT generally outperform unidirectional models on a range of natural language understanding (NLU) tasks, making them the preferred choice for many applications.

The rust-bert crate is a Rust implementation of several state-of-the-art NLP models, based on the Hugging Face Transformers library. It allows Rust developers to leverage powerful pre-trained models like BERT, RoBERTa, GPT, and more for tasks such as sentiment analysis, text generation, and question answering. Built with a focus on performance and safety, rust-bert is especially suitable for applications that require low-latency predictions or are deployed in environments where Rust’s memory management and concurrency capabilities shine. It provides a simple API to load models and perform predictions, enabling Rust users to incorporate advanced NLP tasks directly into their applications without needing Python dependencies.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0.90"

rust-bert = "0.19.0"

use anyhow;

use rust_bert::pipelines::sentiment::SentimentModel;

fn main() -> anyhow::Result<()> {

// Set-up classifier

let sentiment_classifier = SentimentModel::new(Default::default())?;

// Define input

let input = [

"Probably my all-time favorite movie, a story of selflessness, sacrifice and dedication to a noble cause, but it's not preachy or boring.",

"This film tried to be too many things all at once: stinging political satire, Hollywood blockbuster, sappy romantic comedy, family values promo...",

"If you like original gut wrenching laughter you will like this movie. If you are young or old then you will love this movie, hell even my mom liked it.",

];

// Run model

let output = sentiment_classifier.predict(input);

for sentiment in output {

println!("{sentiment:?}");

}

Ok(())

}

In this code, the rust-bert crate's SentimentModel is used to classify the sentiment of a list of text inputs. First, the sentiment model is initialized with default configurations. Then, an array of movie review strings is defined as input. The model's predict method processes these reviews, producing sentiment predictions, which are then printed to the console. Each prediction contains information about the sentiment of the corresponding text, making it straightforward to interpret the model's classification for each review. The anyhow crate is used to handle potential errors, ensuring robust error reporting in case of initialization or prediction failures.

Lets take another example for sentiment analysis. The code sets up a SentimentModel classifier, configures it to use an FNet model pre-trained on the SST2 sentiment analysis dataset, and processes a series of movie reviews to determine the sentiment (positive or negative) expressed in each review. In the code, resources for model configuration, vocabulary, and model weights are loaded from pre-trained files via RemoteResource, which points to specific versions compatible with FNet. The SentimentConfig struct configures the model type to ModelType::FNet and applies these resources. Once initialized, the classifier’s predict method analyzes each review in the input array and prints out the predicted sentiment for each text. This approach illustrates how to integrate sentiment analysis in Rust applications by leveraging a powerful pre-trained model and producing sentiment predictions efficiently with minimal setup.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0.90"

rust-bert = "0.19.0"

use anyhow;

use rust_bert::fnet::{FNetConfigResources, FNetModelResources, FNetVocabResources};

use rust_bert::pipelines::sentiment::{SentimentConfig, SentimentModel};

use rust_bert::pipelines::common::ModelType;

use rust_bert::resources::RemoteResource;

fn main() -> anyhow::Result<()> {

// Set up the classifier with necessary resources

let config_resource = Box::new(RemoteResource::from_pretrained(

FNetConfigResources::BASE_SST2,

));

let vocab_resource = Box::new(RemoteResource::from_pretrained(

FNetVocabResources::BASE_SST2,

));

let model_resource = Box::new(RemoteResource::from_pretrained(

FNetModelResources::BASE_SST2,

));

let sentiment_config = SentimentConfig {

model_type: ModelType::FNet,

model_resource,

config_resource,

vocab_resource,

..Default::default()

};

let sentiment_classifier = SentimentModel::new(sentiment_config)?;

// Define input

let input = [

"Probably my all-time favorite movie, a story of selflessness, sacrifice and dedication to a noble cause, but it's not preachy or boring.",

"This film tried to be too many things all at once: stinging political satire, Hollywood blockbuster, sappy romantic comedy, family values promo...",

"If you like original gut wrenching laughter you will like this movie. If you are young or old then you will love this movie, hell even my mom liked it.",

];

// Run model

let output = sentiment_classifier.predict(input);

for sentiment in output {

println!("{sentiment:?}");

}

Ok(())

}

In industry, bidirectional models such as BERT have been widely adopted for tasks like search engine optimization (Google uses BERT in its search algorithms), chatbots, virtual assistants, and content moderation. Their ability to understand both the context of a query and the content of a document allows them to provide more accurate and contextually relevant results. In applications like virtual assistants or chatbots, BERT’s bidirectional understanding improves response quality by accurately interpreting user queries in real-time.

In conclusion, bidirectional models represent a major advancement in NLP by capturing context from both directions, which significantly improves performance on complex language tasks. While they require more computational resources than unidirectional models, their ability to understand nuanced relationships within text makes them highly effective for tasks such as question answering, sentiment analysis, and machine translation. Implementing and experimenting with these models in Rust provides a robust platform for exploring their advantages over unidirectional models and evaluating their potential for real-world applications in natural language understanding.

5.2. The BERT Architecture

The BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) architecture is a pioneering model in natural language processing (NLP), designed to understand language context by processing input sequences bidirectionally. Unlike Transformer models designed for text generation (such as GPT, which uses an autoregressive approach), BERT is an encoder-only model based entirely on the Transformer encoder stack. This encoder-only structure is key to BERT’s ability to capture rich context from both the left and right of a target word, allowing the model to develop a nuanced understanding of the relationships between words and phrases.

Figure 3: BERT architecture consists of Transformer Encoder.

At its core, the BERT architecture consists of multiple layers of self-attention and feedforward neural networks, as described by the Transformer model. The input sequence is tokenized and converted into word embeddings before being passed through the model. These embeddings are then processed by several layers of multi-head attention, where each word can attend to every other word in the sequence, providing both local and global context. Formally, for a sequence $S = [x_1, x_2, ..., x_n]$, BERT computes contextualized representations $h_i$ for each token $x_i$ in the sequence:

$$ h_i = \text{TransformerEncoder}(x_i | x_1, ..., x_{i-1}, x_{i+1}, ..., x_n) $$

This bidirectional nature allows BERT to leverage information from both preceding and succeeding words, a significant improvement over unidirectional models that can only rely on one direction of context. This is particularly useful for tasks like question answering, where understanding the relationships between different parts of the text is crucial for extracting the correct answer.

BERT’s unique training approach is centered around two main objectives: masked language modeling (MLM) and next sentence prediction (NSP). These objectives allow BERT to learn representations that are transferable across a wide range of NLP tasks.

Masked Language Modeling (MLM): In MLM, BERT randomly masks some percentage (typically 15%) of the tokens in each input sequence and trains the model to predict the masked tokens using the surrounding context. For instance, in the sentence “The cat sat on the \[MASK\],” the model must predict the masked word “mat.” Mathematically, the model maximizes the probability $P(x_m | x_1, ..., x_{m-1}, x_{m+1}, ..., x_n)$, where $x_m$ is the masked token and the rest of the tokens$x_1, x_{m-1}, x_{m+1}, ..., x_n$ provide the bidirectional context. This forces the model to rely on both the left and right context, leading to more accurate predictions and richer word representations.

Next Sentence Prediction (NSP): BERT is also trained to understand the relationships between sentences. During training, the model is given pairs of sentences and learns to predict whether the second sentence follows the first one in the original document. This task is formulated as a binary classification problem, where the model outputs a probability that sentence B follows sentence A. This pre-training objective is particularly useful for tasks like document classification and question answering, where the relationship between multiple sentences or phrases is important.

The pre-training of BERT on large text corpora (such as Wikipedia and BookCorpus) allows the model to learn general language representations that can then be fine-tuned on specific tasks. Fine-tuning involves taking a pre-trained BERT model and training it further on a smaller, task-specific dataset. For example, when fine-tuning BERT on a sentiment analysis task, a classification layer is added on top of the pre-trained model, and the model is trained to predict sentiment labels (e.g., positive or negative) for input sentences. The fine-tuning process is typically much faster than training from scratch, as BERT has already learned general language patterns during pre-training.

The success of BERT is largely attributed to its bidirectional context and masked language modeling, which enable it to capture the relationships between words more effectively than previous models. In contrast to autoregressive models like GPT, which generate text one token at a time and are limited by unidirectional context, BERT’s architecture allows it to process entire sequences at once, leading to improved performance on tasks that require a deep understanding of sentence structure and meaning.

Training BERT from scratch, even on a small corpus, follows the same principles as its pre-training with MLM and NSP tasks. After the model is pre-trained, it can be fine-tuned on specific NLP tasks. For instance, fine-tuning BERT on text classification involves adding a classification head on top of the pre-trained encoder and optimizing the model for a task-specific loss, such as cross-entropy loss in the case of sentiment analysis or binary classification.

Fine-tuning a pre-trained BERT model on a specific NLP task can be easily achieved by loading the pre-trained model and training it on a task-specific dataset. In practice, fine-tuning BERT has led to significant improvements across many NLP tasks, including text classification, named entity recognition (NER), question answering, and paraphrase detection. This process of pre-training followed by fine-tuning has become the dominant paradigm for modern NLP systems, as it allows models to leverage large-scale language understanding while being adaptable to specific domains.

This Rust code demonstrates how to download, configure, and fine-tune a pre-trained BERT model using the rust-bert and tch libraries. Leveraging rust-bert, a Rust port of Hugging Face’s Transformers library, it initializes a BERT model for sequence classification, enabling it to be trained or fine-tuned for specific natural language processing tasks such as sentiment analysis, topic classification, or question answering. The code sets up resources and configuration files, including the model weights, vocabulary, and configuration file, which are downloaded from a remote URL and used to load a pre-trained BERT model.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0.90"

rust-bert = "0.19.0"

tch = "0.8.0"

use anyhow::Result;

use rust_bert::bert::{BertConfig, BertForSequenceClassification};

use rust_bert::resources::{RemoteResource, ResourceProvider};

use rust_bert::Config;

use tch::{Device, nn, nn::OptimizerConfig, Tensor};

fn main() -> Result<()> {

// Set device for training

let device = Device::cuda_if_available();

// Define resources using URLs

let config_resource = RemoteResource::new("https://huggingface.co/bert-base-uncased/resolve/main/config.json", "bert_config.json");

let _vocab_resource = RemoteResource::new("https://huggingface.co/bert-base-uncased/resolve/main/vocab.txt", "bert_vocab.txt");

let weights_resource = RemoteResource::new("https://huggingface.co/bert-base-uncased/resolve/main/rust_model.ot", "bert_model.ot");

// Download resources

let config_path = config_resource.get_local_path()?;

let weights_path = weights_resource.get_local_path()?;

// Load the configuration and model

let config = BertConfig::from_file(config_path);

let mut vs = nn::VarStore::new(device); // `vs` is now mutable

let model = BertForSequenceClassification::new(&vs.root(), &config);

// Load the pre-trained weights

vs.load(weights_path)?;

// Define optimizer

let mut optimizer = nn::Adam::default().build(&vs, 1e-5)?;

// Sample training data: (input_ids, attention_masks, labels)

let input_ids = Tensor::randint(0, &[8, 128], (tch::Kind::Int64, device));

let attention_mask = Tensor::ones(&[8, 128], (tch::Kind::Int64, device));

let labels = Tensor::randint(0, &[8], (tch::Kind::Int64, device));

// Training loop

let num_epochs = 3;

for epoch in 1..=num_epochs {

optimizer.zero_grad();

let output = model

.forward_t(Some(&input_ids), Some(&attention_mask), None, None, None, false);

// Compute loss (cross-entropy loss for classification)

let logits = output.logits;

let loss = logits.cross_entropy_for_logits(&labels);

// Backpropagation

loss.backward();

optimizer.step();

println!("Epoch: {}, Loss: {:?}", epoch, f64::from(loss));

}

println!("Fine-tuning complete!");

Ok(())

}

The code works by first setting up the environment, defining the device (CPU or GPU), and downloading the necessary resources. The BertForSequenceClassification model is initialized with a configuration and the model weights are loaded into memory. Sample data is created for demonstration purposes (real training data would replace it), and an Adam optimizer is set up to manage the training updates. Within the training loop, the model computes the output logits, calculates cross-entropy loss, and performs backpropagation to update the model parameters. After several epochs, the model parameters will be fine-tuned for the specific training data, ready for further evaluation or deployment.

Lets see another Rust code to implement a pipeline for generating sentence embeddings using a pre-trained BERT model. It utilizes the candle_transformers library for loading and running a BERT model, specifically the "all-MiniLM-L6-v2" model from Hugging Face's model repository. The code loads the model and tokenizer, processes a set of predefined sentences, and computes embeddings for each sentence. By leveraging a GPU (if available) to accelerate inference, the code efficiently generates and normalizes embeddings for downstream tasks like similarity calculations between sentences.

[dependencies]

accelerate-src = "0.3.2"

anyhow = "1.0.90"

candle-core = "0.7.2"

candle-nn = "0.7.2"

candle-transformers = "0.7.2"

clap = "4.5.20"

hf-hub = "0.3.2"

serde = "1.0.210"

serde_json = "1.0.132"

tokenizers = "0.20.1"

use candle_transformers::models::bert::{BertModel, Config, HiddenAct, DTYPE};

use anyhow::{Error as E, Result};

use candle_core::{Tensor, Device};

use candle_nn::VarBuilder;

use hf_hub::{api::sync::Api, Repo, RepoType};

use tokenizers::{PaddingParams, Tokenizer};

use std::fs;

fn build_model_and_tokenizer() -> Result<(BertModel, Tokenizer)> {

// Automatically use GPU 0 if available, otherwise fallback to CPU

let device = Device::cuda_if_available(0)?;

let model_id = "sentence-transformers/all-MiniLM-L6-v2".to_string();

let revision = "main".to_string();

let repo = Repo::with_revision(model_id, RepoType::Model, revision);

let (config_filename, tokenizer_filename, weights_filename) = {

let api = Api::new()?;

let api = api.repo(repo);

let config = api.get("config.json")?;

let tokenizer = api.get("tokenizer.json")?;

let weights = api.get("model.safetensors")?;

(config, tokenizer, weights)

};

let config = fs::read_to_string(config_filename)?;

let mut config: Config = serde_json::from_str(&config)?;

let tokenizer = Tokenizer::from_file(tokenizer_filename).map_err(E::msg)?;

let vb = unsafe { VarBuilder::from_mmaped_safetensors(&[weights_filename], DTYPE, &device)? };

config.hidden_act = HiddenAct::GeluApproximate;

let model = BertModel::load(vb, &config)?;

Ok((model, tokenizer))

}

fn main() -> Result<()> {

let (model, mut tokenizer) = build_model_and_tokenizer()?;

let device = &model.device;

// Define a set of sentences for embedding and similarity computation

let sentences = [

"The cat sits outside",

"A man is playing guitar",

"I love pasta",

"The new movie is awesome",

"The cat plays in the garden",

"A woman watches TV",

"The new movie is so great",

"Do you like pizza?",

];

let n_sentences = sentences.len();

// Set padding strategy for batch processing

let pp = PaddingParams {

strategy: tokenizers::PaddingStrategy::BatchLongest,

..Default::default()

};

tokenizer.with_padding(Some(pp));

// Tokenize each sentence and collect the tokens into tensors

let tokens = tokenizer.encode_batch(sentences.to_vec(), true).map_err(E::msg)?;

let token_ids = tokens

.iter()

.map(|tokens| {

let tokens = tokens.get_ids().to_vec();

Ok(Tensor::new(tokens.as_slice(), device)?)

})

.collect::<Result<Vec<_>>>()?;

let attention_mask = tokens

.iter()

.map(|tokens| {

let tokens = tokens.get_attention_mask().to_vec();

Ok(Tensor::new(tokens.as_slice(), device)?)

})

.collect::<Result<Vec<_>>>()?;

// Stack token tensors and prepare them for the model

let token_ids = Tensor::stack(&token_ids, 0)?;

let attention_mask = Tensor::stack(&attention_mask, 0)?;

let token_type_ids = token_ids.zeros_like()?;

println!("Running inference on batch {:?}", token_ids.shape());

let embeddings = model.forward(&token_ids, &token_type_ids, Some(&attention_mask))?;

println!("Generated embeddings {:?}", embeddings.shape());

// Apply mean pooling (average across tokens)

let (_n_sentence, n_tokens, _hidden_size) = embeddings.dims3()?;

let embeddings = (embeddings.sum(1)? / (n_tokens as f64))?;

let embeddings = normalize_l2(&embeddings)?;

println!("Pooled embeddings {:?}", embeddings.shape());

// Calculate cosine similarities between sentences

let mut similarities = vec![];

for i in 0..n_sentences {

let e_i = embeddings.get(i)?;

for j in (i + 1)..n_sentences {

let e_j = embeddings.get(j)?;

let sum_ij = (&e_i * &e_j)?.sum_all()?.to_scalar::<f32>()?;

let sum_i2 = (&e_i * &e_i)?.sum_all()?.to_scalar::<f32>()?;

let sum_j2 = (&e_j * &e_j)?.sum_all()?.to_scalar::<f32>()?;

let cosine_similarity = sum_ij / (sum_i2 * sum_j2).sqrt();

similarities.push((cosine_similarity, i, j))

}

}

// Print the top 5 sentence pairs with the highest similarity scores

similarities.sort_by(|u, v| v.0.total_cmp(&u.0));

for &(score, i, j) in similarities[..5].iter() {

println!("Score: {score:.2} '{}' '{}'", sentences[i], sentences[j]);

}

Ok(())

}

// Function for L2 normalization of embeddings

pub fn normalize_l2(v: &Tensor) -> Result<Tensor> {

Ok(v.broadcast_div(&v.sqr()?.sum_keepdim(1)?.sqrt()?)?)

}

The program begins by setting up the device, loading the model configuration, tokenizer, and weights from Hugging Face's Hub. It then tokenizes a list of example sentences, adding padding to ensure uniform input lengths across sentences in a batch. After encoding the sentences into tensors, it passes them through the BERT model to generate embeddings for each token. The code applies average pooling to obtain a single embedding per sentence and performs L2 normalization on these embeddings to standardize their magnitudes. Finally, it computes cosine similarities between the embeddings, identifying the top 5 most similar sentence pairs based on the highest cosine similarity scores. This process provides insight into semantic relationships between sentences, making it useful for tasks like sentence clustering or similarity-based search.

In recent years, BERT variants such as RoBERTa, DistilBERT, and ALBERT have been introduced, each improving upon the original BERT model in different ways. For example, RoBERTa modifies BERT’s pre-training procedure by removing NSP and increasing the amount of training data, while DistilBERT reduces the size of the model to make it more efficient while retaining most of BERT’s performance.

The latest trends in BERT-based models focus on improving both the efficiency and accuracy of pre-trained language models. This includes innovations such as sparse attention mechanisms, knowledge distillation, and models like T5 and BART, which extend BERT’s architecture for sequence-to-sequence tasks. These advancements continue to push the boundaries of what is possible with pre-trained models, making BERT and its variants indispensable tools in the modern NLP toolkit.

In conclusion, BERT’s architecture represents a major step forward in natural language understanding. By leveraging bidirectional context and training with masked language modeling and next sentence prediction, BERT is able to capture complex language patterns that unidirectional models struggle to understand. The process of pre-training followed by fine-tuning allows BERT to excel across a wide range of NLP tasks, making it one of the most impactful models in the field. Implementing BERT in Rust provides a practical way to explore its architecture and the powerful techniques that enable its success.

5.3. BERT Variants and Extensions

While BERT introduced a breakthrough in natural language processing (NLP) through its bidirectional architecture and masked language modeling, several BERT variants have been developed to further improve the model’s efficiency, training process, and overall performance across a variety of tasks. The most notable of these variants include RoBERTa, ALBERT, and DistilBERT, each of which builds on BERT’s architecture but introduces unique modifications to address challenges like model size, training efficiency, and performance scalability.

RoBERTa (Robustly Optimized BERT Pretraining Approach) modifies BERT’s original training procedure to improve performance on NLP benchmarks. The most significant difference between BERT and RoBERTa lies in how they handle pre-training. RoBERTa removes the Next Sentence Prediction (NSP) task that was part of BERT’s pre-training objective, finding that it was not essential to BERT’s performance. Additionally, RoBERTa uses larger batch sizes and training data (including datasets like CC-News and OpenWebText), and trains the model for a longer duration. By focusing solely on the Masked Language Modeling (MLM) task and optimizing the training process, RoBERTa outperforms BERT on tasks like GLUE and SQuAD. Mathematically, RoBERTa maintains BERT’s MLM objective:

$$ \text{Maximize } P(x_m | x_1, ..., x_{m-1}, x_{m+1}, ..., x_n) $$

However, the removal of NSP simplifies the training process, and the use of larger datasets ensures that RoBERTa can generalize better to a wider range of tasks.

ALBERT (A Lite BERT), in contrast, focuses on reducing the size of the model without sacrificing much of its performance. ALBERT introduces parameter sharing across layers and factorization of the embedding matrix, significantly reducing the number of parameters. In BERT, each layer of the Transformer model has its own set of parameters, but ALBERT shares these parameters across layers, reducing the model’s overall footprint. Additionally, ALBERT factorizes the large embedding matrix into two smaller matrices, reducing the number of parameters in the input embeddings. Formally, ALBERT decomposes the embedding matrix $E$ into two matrices:

$$E = W \times V$$

where $W \in \mathbb{R}^{V \times d}$ and $V \in \mathbb{R}^{d \times H}$, with $V$ being much smaller than the original embedding matrix. This decomposition reduces the overall parameter count, particularly in models trained on large vocabularies. Despite having fewer parameters, ALBERT maintains competitive performance with BERT on several NLP benchmarks. Its efficiency makes it particularly useful in applications where computational resources are limited, such as mobile or edge devices.

DistilBERT introduces the concept of model distillation to create a smaller, faster version of BERT. Distillation is a technique in which a smaller model (the student model) is trained to mimic the behavior of a larger, pre-trained model (the teacher model). DistilBERT reduces the number of layers in the original BERT model by 50%, but it retains approximately 97% of BERT’s language understanding capacity. This is achieved by minimizing a distillation loss function that measures how well the student model replicates the output distributions of the teacher model:

$$ \text{Distillation loss} = \alpha \times L_{\text{soft}}(S, T) + (1 - \alpha) \times L_{\text{hard}}(S, y) $$

where $L_{\text{soft}}$ is the soft target loss between the student (S) and teacher (T) models’ output distributions, and $L_{\text{hard}}$ is the loss computed using the true labels $y$. The coefficient $\alpha$ balances these two loss terms. DistilBERT uses both the output logits and the intermediate layer representations of the teacher model during training, ensuring that the student model can closely approximate the teacher’s behavior despite having fewer layers. This reduction in complexity makes DistilBERT faster to train and deploy, making it suitable for real-time applications where inference speed is crucial, such as in chatbots or virtual assistants.

Parameter reduction techniques, like those used in ALBERT and DistilBERT, highlight the trade-offs between model size, speed, and accuracy. Smaller models, while faster and more resource-efficient, may lose some of the fine-grained language understanding that larger models capture. However, for many practical applications, the performance loss is minimal compared to the significant gains in speed and efficiency. ALBERT, for instance, achieves state-of-the-art performance on several NLP tasks with a fraction of the parameters used by BERT, making it a compelling choice for developers who need to deploy models in environments with limited computational power.

This code demonstrates how to utilize DistilBERT, a compact transformer model, to process NLP inputs in Rust. By loading pretrained model weights and configuration files from Hugging Face’s DistilBERT model, the code initializes DistilBERT on the available device (CPU or GPU). It then performs a forward pass to generate embeddings or hidden states from dummy input data, simulating an NLP workflow that might involve tasks like sentence encoding or classification.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0.90"

rust-bert = "0.19.0"

serde_json = "1.0.132"

tch = "0.8.0"

use anyhow::Result;

use rust_bert::distilbert::{DistilBertConfig, DistilBertModel};

use rust_bert::resources::{RemoteResource, ResourceProvider};

use rust_bert::Config;

use tch::{Device, Tensor};

fn main() -> Result<()> {

// Set device for inference

let device = Device::cuda_if_available();

// Define model resources for DistilBERT

let config_resource = RemoteResource::new(

"https://huggingface.co/distilbert-base-uncased/resolve/main/config.json",

"distilbert_config.json",

);

let weights_resource = RemoteResource::new(

"https://huggingface.co/distilbert-base-uncased/resolve/main/rust_model.ot",

"distilbert_model.ot",

);

// Download and load configuration and weights

let config_path = config_resource.get_local_path()?;

let weights_path = weights_resource.get_local_path()?;

let config = DistilBertConfig::from_file(config_path);

let mut vs = tch::nn::VarStore::new(device);

let distilbert_model = DistilBertModel::new(&vs.root(), &config);

vs.load(weights_path)?;

// Sample input for testing (dummy input for demonstration)

let input_ids = Tensor::randint(config.vocab_size, &[1, 20], (tch::Kind::Int64, device));

let attention_mask = Tensor::ones(&[1, 20], (tch::Kind::Int64, device));

// Forward pass through DistilBERT

let distilbert_output = distilbert_model

.forward_t(Some(&input_ids), Some(&attention_mask), None, false)

.unwrap();

// Extract the hidden states or pooled output if needed

println!("DistilBERT hidden states: {:?}", distilbert_output.hidden_state);

Ok(())

}

The code begins by setting up the necessary resources and loading DistilBERT’s configuration and pretrained weights. After initializing the model, it creates dummy input tensors (input IDs and attention masks), which represent tokenized text inputs that the model can process. When performing a forward pass through DistilBERT, it outputs hidden states, which represent the model’s internal embeddings for each token in the input sequence. These hidden states, printed at the end, can be used for downstream NLP tasks such as sentiment analysis, text classification, or sentence similarity calculations.

In terms of industry use cases, BERT variants like RoBERTa, ALBERT, and DistilBERT are widely used across domains such as search engines, virtual assistants, and customer service automation. RoBERTa is often deployed in scenarios requiring high accuracy and robustness, such as legal document analysis and medical text processing, where understanding the nuanced meaning of text is critical. ALBERT and DistilBERT are favored in environments where computational resources are limited, such as mobile applications, real-time translation systems, and smart devices that need to balance speed with language understanding capabilities.

This Rust code demonstrates how to use the rust-bert library to load and run inference on two popular NLP transformer models: RoBERTa and ALBERT. These models are configured and fine-tuned for sequence classification tasks, allowing them to process text inputs and output classification logits. Using tch (Torch in Rust), the code efficiently leverages model resources, loading configuration and model weights from URLs. By specifying resources and paths, the code enables seamless downloads, configuration, and use of these pre-trained transformer models in Rust.

use anyhow::Result;

use rust_bert::albert::{AlbertConfig, AlbertForSequenceClassification};

use rust_bert::roberta::{RobertaConfig, RobertaForSequenceClassification};

use rust_bert::resources::{RemoteResource, ResourceProvider};

use tch::{Device, nn, Tensor};

use rust_bert::Config;

fn main() -> Result<()> {

// Set device for inference

let device = Device::cuda_if_available();

// ======== RoBERTa Model ========

println!("Loading RoBERTa model...");

let roberta_config_resource = RemoteResource::new(

"https://huggingface.co/roberta-base/resolve/main/config.json",

"roberta_config.json",

);

let roberta_weights_resource = RemoteResource::new(

"https://huggingface.co/roberta-base/resolve/main/rust_model.ot",

"roberta_model.ot",

);

// Download resources for RoBERTa

let roberta_config_path = roberta_config_resource.get_local_path()?;

let roberta_weights_path = roberta_weights_resource.get_local_path()?;

// Load RoBERTa configuration and weights

let roberta_config = RobertaConfig::from_file(roberta_config_path);

let mut roberta_vs = nn::VarStore::new(device);

let roberta_model = RobertaForSequenceClassification::new(&roberta_vs.root(), &roberta_config);

roberta_vs.load(roberta_weights_path)?;

// Define sample input for RoBERTa

let roberta_input_ids = Tensor::randint(50265, &[1, 10], (tch::Kind::Int64, device));

let roberta_attention_mask = Tensor::ones(&[1, 10], (tch::Kind::Int64, device));

// Perform forward pass for RoBERTa

let roberta_output = roberta_model.forward_t(

Some(&roberta_input_ids),

Some(&roberta_attention_mask),

None,

None,

None,

false,

);

println!("RoBERTa output logits: {:?}", roberta_output.logits);

// ======== ALBERT Model ========

println!("\nLoading ALBERT model...");

let albert_config_resource = RemoteResource::new(

"https://huggingface.co/albert-base-v2/resolve/main/config.json",

"albert_config.json",

);

let albert_weights_resource = RemoteResource::new(

"https://huggingface.co/albert-base-v2/resolve/main/rust_model.ot",

"albert_model.ot",

);

// Download resources for ALBERT

let albert_config_path = albert_config_resource.get_local_path()?;

let albert_weights_path = albert_weights_resource.get_local_path()?;

// Load ALBERT configuration and weights

let albert_config = AlbertConfig::from_file(albert_config_path);

let mut albert_vs = nn::VarStore::new(device);

let albert_model = AlbertForSequenceClassification::new(&albert_vs.root(), &albert_config);

albert_vs.load(albert_weights_path)?;

// Define sample input for ALBERT

let albert_input_ids = Tensor::randint(30000, &[1, 10], (tch::Kind::Int64, device));

let albert_attention_mask = Tensor::ones(&[1, 10], (tch::Kind::Int64, device));

// Perform forward pass for ALBERT

let albert_output = albert_model.forward_t(

Some(&albert_input_ids),

Some(&albert_attention_mask),

None,

None,

None,

false,

);

println!("ALBERT output logits: {:?}", albert_output.logits);

Ok(())

}

The code first sets up a device (CPU or CUDA if available) to run the models. It then configures and loads resources for both the RoBERTa and ALBERT models, utilizing RemoteResource to download their configurations and pre-trained weights. The models are created with RobertaForSequenceClassification and AlbertForSequenceClassification, initialized from their respective configurations, and loaded into variable stores for efficient management. Each model is then provided with random input tensors representing token IDs and attention masks, simulating the structure of actual text input. Finally, the forward_t method performs a forward pass for both models, producing output logits that would be used in real classification tasks. The use of Rust’s error handling and type system ensures robust management of resources and model computations.

The latest trends in BERT variants and extensions continue to focus on making models more efficient while retaining high levels of performance. Knowledge distillation, as seen in DistilBERT, is being extended to larger models and more complex tasks, while researchers are exploring new ways to reduce the computational cost of attention mechanisms, such as sparse attention and linear attention. Additionally, hybrid models combining the best features of various architectures (e.g., combining BERT’s bidirectionality with GPT’s autoregressive capabilities) are being developed to tackle even more challenging NLP tasks.

In conclusion, BERT variants like RoBERTa, ALBERT, and DistilBERT have made significant contributions to NLP by optimizing the original BERT architecture for different use cases. Whether focusing on improving training efficiency, reducing model size, or speeding up inference, these variants have broadened the applicability of BERT-based models across a wide range of tasks and industries. Implementing these variants in Rust provides an opportunity to explore their architectural innovations and optimize them for deployment in resource-constrained environments.

5.4. Fine-Tuning BERT for Specific NLP Tasks

Fine-tuning BERT for specific NLP tasks such as sentiment analysis, named entity recognition (NER), and question answering is one of the most powerful aspects of its architecture. BERT’s pre-training on vast amounts of text data gives it a rich understanding of language, but to apply BERT to specific applications, the model must be fine-tuned. Fine-tuning involves adapting the pre-trained BERT representations to particular tasks by training the model on task-specific datasets. During this process, the task-specific layer (such as a classification head) is added on top of the pre-trained BERT model, and both the task-specific layer and the underlying BERT parameters are adjusted to optimize the model for the task at hand.

Formally, the process of fine-tuning involves taking the output representations from BERT for a sequence $S = [x_1, x_2, ..., x_n]$ and passing them through task-specific layers to produce the final output. For example, in classification tasks such as sentiment analysis, the output of the \[CLS\] token (a special token used by BERT to represent the entire sequence) is passed through a linear layer with softmax activation to predict the class probabilities:

$$ \hat{y} = \text{softmax}(W h_{\text{[CLS]}} + b) $$

where $h_{\text{[CLS]}}$ is the hidden state corresponding to the \[CLS\] token, $W$ and $b$ are the learnable parameters of the classification layer, and $\hat{y}$ represents the predicted probabilities for each class (e.g., positive or negative sentiment).

Fine-tuning strategies vary depending on the specific task and dataset size. One common approach is freezing the majority of BERT’s layers and training only the task-specific layer, which prevents overfitting when fine-tuning on smaller datasets. In this case, the pre-trained weights of BERT are kept fixed, and only the parameters of the final task-specific layer are updated during training. For larger datasets or tasks requiring deeper language understanding, fine-tuning the entire model can lead to better performance, as all the layers of BERT are allowed to adjust to the task.

The challenge in fine-tuning large models like BERT on small datasets arises from the risk of overfitting. Due to BERT's massive parameter count (e.g., 110 million parameters in BERT-Base), it can easily overfit small datasets if regularization techniques are not applied. Common techniques to prevent overfitting include dropout, early stopping, and weight decay. Dropout works by randomly disabling neurons during training, ensuring that the model does not rely too heavily on any single feature. Weight decay introduces a penalty on the magnitude of the model’s weights, encouraging the model to learn simpler and more generalizable patterns. These regularization techniques can be incorporated into the fine-tuning process to enhance the model’s ability to generalize beyond the training data.

During fine-tuning, it is crucial to carefully tune the learning rate. BERT models are sensitive to learning rate choices due to the complexity of their layers. Fine-tuning typically requires smaller learning rates than standard training. A learning rate that is too large can cause the model to lose the language knowledge learned during pre-training, while a learning rate that is too small can slow down the fine-tuning process. In practice, learning rate schedules, such as linear warm-up followed by decay, are commonly employed to gradually increase the learning rate during the first few epochs, followed by a steady decay, which helps achieve stable fine-tuning.

One of the key advantages of BERT’s architecture is that the same pre-trained model can be adapted to a wide variety of tasks through fine-tuning, which has been demonstrated across many industry use cases. For example, Google fine-tuned BERT for search query understanding in their search engine, dramatically improving the relevance of search results by understanding the intent behind user queries. Similarly, financial institutions have fine-tuned BERT models for fraud detection and sentiment analysis of financial news, allowing them to better understand market trends and customer behavior.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0.90"

rust-bert = "0.19.0"

tch = "0.8.0"

use anyhow::Result;

use rust_bert::bert::{BertConfig, BertForSequenceClassification};

use rust_bert::resources::{RemoteResource, ResourceProvider};

use rust_bert::Config;

use tch::{Device, Tensor, nn, nn::OptimizerConfig, Kind};

fn main() -> Result<()> {

// Specify the device (CPU or GPU)

let device = Device::cuda_if_available();

// Load the BERT configuration and model resources

let config_resource = RemoteResource::new(

"https://huggingface.co/bert-base-uncased/resolve/main/config.json",

"bert_config.json",

);

let weights_resource = RemoteResource::new(

"https://huggingface.co/bert-base-uncased/resolve/main/rust_model.ot",

"bert_model.ot",

);

// Load resources

let config_path = config_resource.get_local_path()?;

let weights_path = weights_resource.get_local_path()?;

// Load the BERT configuration

let config = BertConfig::from_file(config_path);

let mut vs = nn::VarStore::new(device);

// Initialize BertForSequenceClassification with the number of labels for classification

let model = BertForSequenceClassification::new(&vs.root(), &config);

// Load pre-trained weights into the model

vs.load(weights_path)?;

// Set up an optimizer (Adam)

let mut optimizer = nn::Adam::default().build(&vs, 1e-5)?;

// Define some dummy input data (you would replace this with your actual task-specific data)

let input_ids = Tensor::randint(config.vocab_size, &[32, 64], (Kind::Int64, device)); // batch of 32, sequence length of 64

let attention_mask = Tensor::ones(&[32, 64], (Kind::Int64, device));

let labels = Tensor::randint(2, &[32], (Kind::Int64, device)); // binary classification task

// Training loop

let num_epochs = 3;

for epoch in 1..=num_epochs {

optimizer.zero_grad();

// Forward pass through the BERT model

let output = model

.forward_t(

Some(&input_ids),

Some(&attention_mask),

None, None, None, false,

);

let logits = output.logits; // Extract logits

let loss = logits.cross_entropy_for_logits(&labels); // Calculate cross-entropy loss

// Backward pass and optimization step

loss.backward();

optimizer.step();

// Print the loss for each epoch

println!("Epoch: {}, Loss: {:?}", epoch, f64::from(&loss));

}

println!("Fine-tuning complete!");

Ok(())

}

One of the challenges when fine-tuning BERT is handling small datasets, where the model may overfit due to its large number of parameters. One strategy to mitigate this issue is using transfer learning, where BERT is pre-trained on a larger dataset and fine-tuned on a smaller task-specific dataset. Data augmentation techniques, such as synonym replacement or back-translation, can also be employed to artificially increase the size of the training data and improve generalization.

Lets see another example. The following Rust code demonstrates a pipeline for generating and processing sentence embeddings using a pre-trained DistilBERT model. It leverages the candle_transformers library to load the DistilBERT model from Hugging Face's model hub, tokenize input text, and compute embeddings. The setup is designed to automatically utilize a GPU if available, which accelerates model inference. By encoding a given prompt into embeddings, the code provides a compact representation of the input text, suitable for downstream natural language processing tasks like text similarity or clustering.

[dependencies]

accelerate-src = "0.3.2"

anyhow = "1.0.90"

candle-core = "0.7.2"

candle-nn = "0.7.2"

candle-transformers = "0.7.2"

clap = "4.5.20"

hf-hub = "0.3.2"

serde = "1.0.210"

serde_json = "1.0.132"

tokenizers = "0.20.1"

use candle_transformers::models::distilbert::{Config, DistilBertModel, DTYPE};

use anyhow::{Error as E, Result};

use candle_core::{Device, Tensor};

use candle_nn::VarBuilder;

use hf_hub::{api::sync::Api, Repo, RepoType};

use tokenizers::Tokenizer;

use std::fs;

fn build_model_and_tokenizer() -> Result<(DistilBertModel, Tokenizer)> {

// Automatically use GPU 0 if available, otherwise fallback to CPU

let device = Device::cuda_if_available(0)?;

let model_id = "sentence-transformers/all-MiniLM-L6-v2".to_string();

let revision = "main".to_string();

let repo = Repo::with_revision(model_id, RepoType::Model, revision);

let (config_filename, tokenizer_filename, weights_filename) = {

let api = Api::new()?;

let api = api.repo(repo);

let config = api.get("config.json")?;

let tokenizer = api.get("tokenizer.json")?;

let weights = api.get("model.safetensors")?;

(config, tokenizer, weights)

};

let config = fs::read_to_string(config_filename)?;

let config: Config = serde_json::from_str(&config)?;

let tokenizer = Tokenizer::from_file(tokenizer_filename).map_err(E::msg)?;

let vb = unsafe { VarBuilder::from_mmaped_safetensors(&[weights_filename], DTYPE, &device)? };

let model = DistilBertModel::load(vb, &config)?;

Ok((model, tokenizer))

}

fn get_mask(size: usize, device: &Device) -> Tensor {

let mask: Vec<_> = (0..size)

.flat_map(|i| (0..size).map(move |j| u8::from(j > i)))

.collect();

Tensor::from_slice(&mask, (size, size), device).unwrap()

}

fn main() -> Result<()> {

let prompt = "Example prompt to encode"; // Hardcoded prompt text

let normalize_embeddings = true;

let (model, mut tokenizer) = build_model_and_tokenizer()?;

let device = &model.device;

// Prepare tokenizer and encode the prompt

let tokenizer = tokenizer

.with_padding(None)

.with_truncation(None)

.map_err(E::msg)?;

let tokens = tokenizer

.encode(prompt, true)

.map_err(E::msg)?

.get_ids()

.to_vec();

let token_ids = Tensor::new(&tokens[..], device)?.unsqueeze(0)?;

let mask = get_mask(tokens.len(), device);

println!("token_ids: {:?}", token_ids.to_vec2::<u32>());

println!("mask: {:?}", mask.to_vec2::<u8>());

// Run the forward pass to get embeddings

let ys = model.forward(&token_ids, &mask)?;

println!("{ys}");

// Optionally normalize embeddings

if normalize_embeddings {

let normalized_ys = normalize_l2(&ys)?;

println!("Normalized embeddings: {:?}", normalized_ys);

}

Ok(())

}

// Function for L2 normalization of embeddings

pub fn normalize_l2(v: &Tensor) -> Result<Tensor> {

Ok(v.broadcast_div(&v.sqr()?.sum_keepdim(1)?.sqrt()?)?)

}

The program begins by loading the DistilBERT model and tokenizer configuration files and weights from Hugging Face's hub using the build_model_and_tokenizer function. This function initializes the device (GPU if available, otherwise CPU), downloads the model assets, and constructs the model and tokenizer. In the main function, a hardcoded prompt is tokenized, padded, and converted into tensors. An attention mask, created by get_mask, is applied to the tensor to ensure that only valid tokens are attended to during model inference. The token tensor is then passed through the model to generate embeddings, which can be optionally normalized using the normalize_l2 function. This process standardizes the embeddings, making them suitable for similarity comparisons and other vector-based analyses.

In imbalanced datasets, where certain classes (e.g., positive sentiment) are much more frequent than others (e.g., negative sentiment), fine-tuning BERT can result in biased predictions. To address this, techniques like class weighting or oversampling the minority class can be used to ensure that the model learns balanced representations. Additionally, early stopping can be employed to halt training when the model’s performance on a validation set begins to degrade, further preventing overfitting.

In recent industry trends, fine-tuning BERT and its variants has been used in legal text analysis, where models are adapted to tasks like contract classification and entity extraction from legal documents. Fine-tuning BERT on domain-specific datasets has also led to advancements in medical NLP, where BERT models are used for tasks like medical report summarization and disease classification.

In conclusion, fine-tuning BERT for specific NLP tasks is a powerful method that leverages the general language understanding developed during pre-training. By adding task-specific layers and carefully optimizing the model, BERT can be adapted to a wide variety of tasks, from sentiment analysis to named entity recognition. Implementing fine-tuning pipelines in Rust allows for an efficient and flexible approach to model development, enabling researchers and developers to explore the full potential of BERT-based models in real-world applications.

5.5. Applications of BERT and Its Variants

The BERT model and its variants have had a transformative impact on various natural language processing (NLP) tasks. From text classification to machine translation and sentiment analysis, BERT's ability to generate high-quality contextual representations has made it the foundation of state-of-the-art NLP systems. One of the primary reasons for BERT's success in these applications is its capability to leverage transfer learning—pre-training on a large corpus and fine-tuning on specific tasks with minimal architectural modifications. This approach has significantly improved the performance of models on tasks like question answering (as seen in benchmarks like SQuAD) and natural language inference (as evaluated by datasets like MNLI).

In text classification, BERT has proven to be highly effective because of its bidirectional attention mechanism, which captures context from both the left and right sides of the target word. Given a sequence $S = [x_1, x_2, ..., x_n]$, BERT computes a representation for the entire sequence using the special \[CLS\] token, which is used to classify the input into predefined categories. For instance, in sentiment analysis, the goal is to classify whether a review or sentence expresses positive, negative, or neutral sentiment. BERT fine-tunes its pre-trained weights on sentiment analysis datasets by adding a task-specific classification layer on top of the \[CLS\] token and optimizing a cross-entropy loss:

$$ L_{\text{classification}} = - \sum_{i=1}^{n} y_i \log(\hat{y}_i) $$

where $y_i$ are the true labels and $\hat{y}_i$ are the predicted class probabilities. This architecture allows BERT to achieve impressive results in text classification tasks, outperforming traditional models that rely on handcrafted features or shallow neural networks.

BERT's success in machine translation is also noteworthy. Although BERT itself is not inherently designed for translation (as it is an encoder-only model), variants such as mBERT (Multilingual BERT) and BART (Bidirectional and Autoregressive Transformers) have been adapted for sequence-to-sequence tasks. In these models, the encoder-decoder architecture is critical for translating input sequences from one language to another. For instance, given a sentence in English, the encoder processes the input and generates a context-rich representation, which the decoder uses to generate the corresponding sentence in the target language, such as French. The ability of models like BERT to capture deep contextual meaning allows them to excel in translation tasks, where understanding long-range dependencies is crucial.

One of the most prominent applications of BERT has been in question answering (QA) tasks, particularly those evaluated on the SQuAD (Stanford Question Answering Dataset) benchmark. In QA tasks, BERT is given a context paragraph and a question, and it is required to predict the start and end tokens of the answer within the context. BERT’s bidirectional attention helps the model focus on the most relevant parts of the paragraph when answering the question. Mathematically, the QA task involves predicting the probability distributions $P_{\text{start}}(i)$ and $P_{\text{end}}(i)$ for each token $i$ in the context:

$$ \hat{y}_{\text{start}} = \arg\max P_{\text{start}}(i), \quad \hat{y}_{\text{end}} = \arg\max P_{\text{end}}(i) $$

By maximizing these probabilities, BERT selects the most likely span in the text to answer the question. The model's ability to perform at a human-like level in QA tasks underscores its effectiveness in natural language understanding (NLU).

Despite its remarkable performance, using BERT in real-world applications comes with certain limitations, particularly in terms of computational costs and scalability. BERT is a large model (BERT-Base has 110 million parameters), and running inference on large datasets or deploying BERT-based models in production environments can be challenging. The memory footprint and computation time required for BERT can be prohibitive, especially in applications where low latency is critical, such as real-time chatbots or virtual assistants. To address these limitations, BERT variants such as DistilBERT and ALBERT have been developed, offering lightweight alternatives that retain most of BERT's accuracy while significantly reducing model size and inference time. These models use techniques like model distillation and parameter sharing to optimize performance for real-time use cases.

The versatility of BERT across different domains is another key factor in its widespread adoption. Transfer learning allows BERT to be fine-tuned on task-specific datasets with minimal architectural changes, making it highly adaptable. For example, in the medical domain, BERT has been fine-tuned on clinical notes for tasks such as disease prediction and medical report generation. Similarly, in finance, BERT-based models are used to perform sentiment analysis on financial news, helping institutions gauge market trends. The ability to fine-tune BERT for domain-specific tasks has enabled its deployment in diverse industries with high accuracy and relatively low overhead in model training.

The future directions for BERT-based models in NLP involve tackling more complex tasks and improving model efficiency. Researchers are exploring ways to make BERT more interpretable for tasks like explainable AI and are developing more efficient architectures, such as sparse attention mechanisms, to reduce the computational cost of training and inference. Additionally, the integration of multimodal learning (combining text, images, and other data) is an emerging trend, with models like VisualBERT and UNITER extending BERT's capabilities beyond text to handle tasks like image captioning and video understanding.

The provided Rust code demonstrates the implementation of a question-answering model using the rust-bert library, specifically leveraging the Longformer model architecture. Longformer, optimized for handling long contexts, is particularly well-suited for tasks requiring the model to process extended text passages efficiently. The code sets up and configures a Longformer-based question-answering model, which is then used to answer questions based on given contextual paragraphs.

use anyhow;

use rust_bert::longformer::{

LongformerConfigResources, LongformerMergesResources, LongformerModelResources,

LongformerVocabResources,

};

use rust_bert::pipelines::question_answering::{

QaInput, QuestionAnsweringConfig, QuestionAnsweringModel,

};

use rust_bert::resources::RemoteResource;

use rust_bert::pipelines::common::ModelType;

fn main() -> anyhow::Result<()> {

// Set up the Question Answering model

let config = QuestionAnsweringConfig::new(

ModelType::Longformer,

RemoteResource::from_pretrained(LongformerModelResources::LONGFORMER_BASE_SQUAD1),

RemoteResource::from_pretrained(LongformerConfigResources::LONGFORMER_BASE_SQUAD1),

RemoteResource::from_pretrained(LongformerVocabResources::LONGFORMER_BASE_SQUAD1),

Some(RemoteResource::from_pretrained(

LongformerMergesResources::LONGFORMER_BASE_SQUAD1,

)),

false,

None,

false,

);

let qa_model = QuestionAnsweringModel::new(config)?;

// Define input

let question_1 = String::from("Where does Jaisy live?");

let context_1 = String::from("Jaisy lives in Jakarta");

let question_2 = String::from("Where does Evan live?");

let context_2 = String::from("While Jaisy lives in Jakarta, Evan is in The Hague.");

let qa_input_1 = QaInput {

question: question_1,

context: context_1,

};

let qa_input_2 = QaInput {

question: question_2,

context: context_2,

};

// Get answers

let answers = qa_model.predict(&[qa_input_1, qa_input_2], 1, 32);

println!("{:?}", answers);

Ok(())

}

The code first initializes a QuestionAnsweringConfig with pre-trained resources for the Longformer model, configuration, vocabulary, and merge files, all retrieved from the rust-bert library’s remote resources. The QuestionAnsweringModel is then instantiated with this configuration. After setting up the model, two QaInput instances are created, each containing a question and corresponding context. These inputs are passed to the model’s predict method, which outputs answers by identifying relevant spans within the provided contexts. The resulting answers are printed to the console, showcasing how the model interprets and extracts information from the input contexts to answer the questions.

Lets see another example. The following Rust program implements a text summarization pipeline using the rust-bert library, specifically leveraging the T5 (Text-To-Text Transfer Transformer) model. Text summarization is a common NLP task where the goal is to condense a given text into a shorter version that retains the original meaning. Here, the program sets up a T5 model pre-trained on summarization tasks, loads the necessary model resources (configuration, vocabulary, and weights), and then uses it to summarize a passage describing a recent scientific discovery regarding an exoplanet.

use anyhow;

use rust_bert::pipelines::summarization::{SummarizationConfig, SummarizationModel};

use rust_bert::resources::RemoteResource;

use rust_bert::t5::{T5ConfigResources, T5ModelResources, T5VocabResources};

use rust_bert::pipelines::common::ModelType;

fn main() -> anyhow::Result<()> {

// Define model resources directly using `RemoteResource`

let config_resource = RemoteResource::from_pretrained(T5ConfigResources::T5_SMALL);

let vocab_resource = RemoteResource::from_pretrained(T5VocabResources::T5_SMALL);

let weights_resource = RemoteResource::from_pretrained(T5ModelResources::T5_SMALL);

// Set up summarization configuration with a dummy RemoteResource for merges

let dummy_merges_resource = RemoteResource::from_pretrained(T5VocabResources::T5_SMALL);

let summarization_config = SummarizationConfig::new(

ModelType::T5,

weights_resource,

config_resource,

vocab_resource,

dummy_merges_resource, // Provide a dummy resource here

);

// Initialize summarization model

let summarization_model = SummarizationModel::new(summarization_config)?;

let input = ["In findings published Tuesday in Cornell University's arXiv by a team of scientists \

from the University of Montreal and a separate report published Wednesday in Nature Astronomy by a team \

from University College London (UCL), the presence of water vapour was confirmed in the atmosphere of K2-18b, \

a planet circling a star in the constellation Leo. This is the first such discovery in a planet in its star's \

habitable zone — not too hot and not too cold for liquid water to exist. The Montreal team, led by Björn Benneke, \

used data from the NASA's Hubble telescope to assess changes in the light coming from K2-18b's star as the planet \

passed between it and Earth. They found that certain wavelengths of light, which are usually absorbed by water, \

weakened when the planet was in the way, indicating not only does K2-18b have an atmosphere, but the atmosphere \

contains water in vapour form. The team from UCL then analyzed the Montreal team's data using their own software \

and confirmed their conclusion. This was not the first time scientists have found signs of water on an exoplanet, \

but previous discoveries were made on planets with high temperatures or other pronounced differences from Earth. \

\"This is the first potentially habitable planet where the temperature is right and where we now know there is water,\" \

said UCL astronomer Angelos Tsiaras. \"It's the best candidate for habitability right now.\" \"It's a good sign\", \

said Ryan Cloutier of the Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, who was not one of either study's authors. \

\"Overall,\" he continued, \"the presence of water in its atmosphere certainly improves the prospect of K2-18b being \

a potentially habitable planet, but further observations will be required to say for sure. \" \

K2-18b was first identified in 2015 by the Kepler space telescope. It is about 110 light-years from Earth and larger \

but less dense. Its star, a red dwarf, is cooler than the Sun, but the planet's orbit is much closer, such that a year \

on K2-18b lasts 33 Earth days. According to The Guardian, astronomers were optimistic that NASA's James Webb space \

telescope — scheduled for launch in 2021 — and the European Space Agency's 2028 ARIEL program, could reveal more \

about exoplanets like K2-18b."];

// Credits: WikiNews, CC BY 2.5 license

let output = summarization_model.summarize(&input);

for sentence in output {

println!("{sentence}");

}

Ok(())

}

The code first initializes the model configuration and resources, which include loading the T5 model's weights, vocabulary, and configuration files. A placeholder resource is used for the merges parameter since T5 doesn’t require it. Using these resources, a SummarizationModel instance is created to handle the summarization task. The program then defines an input text, representing a complex scientific article, which is passed to the model’s summarize function. The output is a summarized version of the article, printed line by line, showcasing the T5 model’s capability to generate concise and coherent summaries of lengthy texts. This example demonstrates how Rust can be used for sophisticated NLP tasks by leveraging pre-trained transformer models.

Now let see Rust code to implement a multilingual translation model using T5 model, pre-trained to perform translation tasks. The program loads the T5 base model configuration, vocabulary, and weights from remote resources, which are pre-trained and hosted online. It sets up translation configurations that support translation from English into multiple languages, such as French, German, and Romanian. After initializing the translation model, it translates a sample English sentence into each of the specified target languages and prints the translated outputs.

use anyhow;

use rust_bert::pipelines::common::ModelType;

use rust_bert::pipelines::translation::{Language, TranslationConfig, TranslationModel};

use rust_bert::resources::RemoteResource;

use rust_bert::t5::{T5ConfigResources, T5ModelResources, T5VocabResources};

use tch::Device;

fn main() -> anyhow::Result<()> {

let model_resource = RemoteResource::from_pretrained(T5ModelResources::T5_BASE);

let config_resource = RemoteResource::from_pretrained(T5ConfigResources::T5_BASE);

let vocab_resource = RemoteResource::from_pretrained(T5VocabResources::T5_BASE);

let merges_resource = RemoteResource::from_pretrained(T5VocabResources::T5_BASE); // Dummy resource for merges

let source_languages = [

Language::English,

Language::French,

Language::German,

Language::Indonesian,

];

let target_languages = [

Language::English,

Language::French,

Language::German,

Language::Indonesian,

];

let translation_config = TranslationConfig::new(

ModelType::T5,

model_resource,

config_resource,

vocab_resource,

merges_resource,

source_languages,

target_languages,

Device::cuda_if_available(),

);

let model = TranslationModel::new(translation_config)?;

let source_sentence = "This sentence will be translated in multiple languages.";

let mut outputs = Vec::new();

outputs.extend(model.translate(&[source_sentence], Language::English, Language::French)?);

outputs.extend(model.translate(&[source_sentence], Language::English, Language::German)?);

outputs.extend(model.translate(&[source_sentence], Language::English, Language::Romanian)?);

for sentence in outputs {

println!("{sentence}");

}

Ok(())

}

This code showcases how to configure and use the rust-bert library to handle complex NLP tasks, specifically translation, by leveraging T5's capabilities. It initializes the model using TranslationConfig, which specifies the model type, resources, source and target languages, and the device (CPU or GPU). For each language translation, the translate method of TranslationModel is invoked, translating the source sentence from English to the target language, with the results stored in a vector. By the end, each translated sentence is output to the console, demonstrating T5’s multilingual translation capabilities through a structured and reusable Rust program.

In conclusion, BERT and its variants have become indispensable in modern NLP due to their versatility, transfer learning capabilities, and performance across a wide range of tasks. While computational costs remain a challenge, lightweight variants like DistilBERT and ALBERT offer practical solutions for real-time applications. Implementing BERT-based models in Rust enables developers to take advantage of the language's performance benefits, making BERT well-suited for production-level NLP tasks across diverse industries.

5.6. Model Interpretability and Explainability

As BERT and its variants become increasingly deployed in critical applications such as healthcare, finance, and legal systems, the need for model interpretability and explainability has become paramount. Understanding how BERT models arrive at their predictions is crucial in high-stakes domains, where decisions made by the model may have far-reaching consequences. For example, in applications like loan approval or medical diagnosis, stakeholders must be able to trust the model’s decisions and understand the reasoning behind them. However, interpreting the decisions of complex models like BERT is inherently challenging due to their deep neural network architectures, which involve multiple layers of self-attention and transformer blocks.