Chapter 4

The Transformer Architecture

"The Transformer model represents a paradigm shift in machine learning, proving that attention mechanisms, when implemented correctly, can significantly outperform traditional methods in handling sequential data." — Geoffrey Hinton

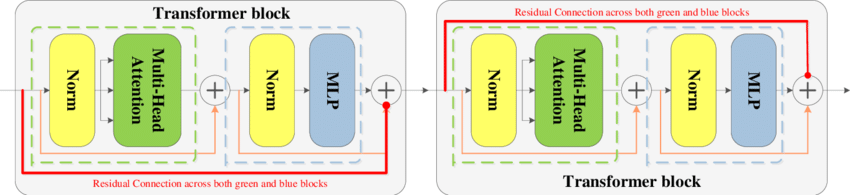

This chaper provides a comprehensive exploration of the key components that make the Transformer model the foundation of modern large language models. This chapter begins with an introduction to the Transformer architecture, explaining how it revolutionized natural language processing through its parallelization capabilities. It delves into the self-attention mechanism, which allows the model to weigh the importance of different words in a sentence, followed by a detailed discussion on multi-head attention, where multiple attention heads capture varied contextual relationships. The chapter further explains positional encoding, crucial for representing the order of words, and breaks down the encoder-decoder architecture that powers complex tasks like translation. Layer normalization and residual connections, essential for stable and efficient training, are thoroughly discussed, alongside training and optimization techniques that enhance performance. Finally, the chapter concludes with real-world applications of the Transformer model, highlighting its impact on various NLP tasks like machine translation, text generation, and summarization.

4.1. Introduction to the Transformer Model

The introduction of the Transformer model revolutionized Natural Language Processing (NLP) by overcoming key limitations of traditional architectures like Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs). Both RNNs and CNNs, while effective in many sequence-based tasks, struggle to handle long-range dependencies in text. In RNNs, sequential data must be processed one time step at a time, making it challenging to capture dependencies between distant tokens, especially in long sequences. This sequential nature also limits parallelization during training and inference, significantly reducing efficiency. CNNs, although better at handling parallel computation, are constrained by the size of the convolutional filters, making them unsuitable for modeling dependencies that span large sections of a text. These limitations created a need for a model that could both efficiently process long-range dependencies and scale with modern hardware. This need led to the development of the Transformer model.

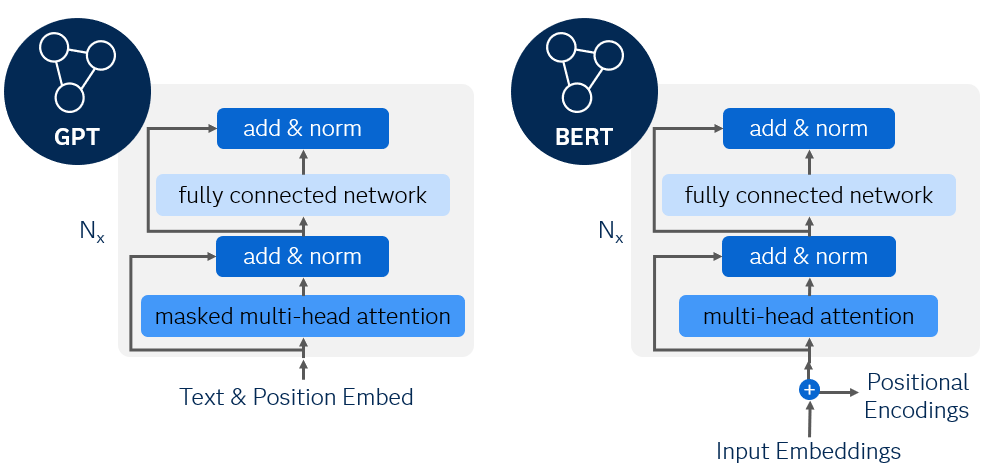

The Transformer architecture, introduced in the paper Attention is All You Need, addressed these challenges by replacing the recurrence and convolutions with a mechanism called self-attention. This key innovation allows the Transformer to capture relationships between tokens regardless of their distance in the sequence, all while processing the sequence in parallel. The architecture consists of two primary components: the Encoder and the Decoder, both of which are built using self-attention layers and feedforward neural networks. The encoder processes the input sequence and produces a set of context-aware representations, while the decoder generates output sequences by attending to both the encoded input and the previously generated output. This modular structure is highly flexible and can be adapted to various NLP tasks, such as translation, text generation, and summarization.

Mathematically, the self-attention mechanism forms the core of the Transformer model. Given an input sequence $X = [x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n]$, the model first transforms each token into three vectors: Query $Q$, Key $K$, and Value $V$. The attention mechanism computes a weighted sum of the value vectors, where the weights are determined by the dot product of the query and key vectors. The scaled dot-product attention is defined as:

$$ \text{Attention}(Q, K, V) = \text{softmax}\left( \frac{QK^T}{\sqrt{d_k}} \right) V $$

Here, $d_k$ is the dimensionality of the key vectors, and the softmax function ensures that the attention weights sum to 1, forming a probability distribution. This allows the model to focus more on the parts of the input that are relevant to the current token, capturing both short- and long-range dependencies in a single step. By computing attention for all tokens in parallel, the Transformer can process an entire sequence efficiently, making it highly scalable and well-suited for large datasets.

One of the key advantages of the Transformer model is its shift from sequential to parallel processing. Traditional RNNs process one token at a time, making it difficult to parallelize across multiple processing units. In contrast, the Transformer processes all tokens in a sequence simultaneously, enabling massive speedups on modern hardware such as GPUs and TPUs. This parallelization is crucial when working with large corpora of text or long sequences, as it significantly reduces training time while maintaining high performance. The ability to handle long sequences efficiently has made the Transformer model the foundation for many state-of-the-art language models, such as BERT and GPT.

Figure 1: GPT vs BERT architecture.

The attention mechanism in the Transformer plays a central role in improving both the efficiency and effectiveness of the model. Unlike RNNs, which struggle to capture long-range dependencies due to the vanishing gradient problem, attention allows the Transformer to attend directly to any part of the input, regardless of its distance. This makes the model more robust in tasks that require understanding complex, long-distance relationships between words. For example, in machine translation, the Transformer can directly map words in the source sentence to the appropriate words in the target sentence, even when these words are far apart.

In addition to implementing the Transformer architecture, benchmarking its performance on a small NLP dataset can provide insights into how it compares to traditional RNNs. A key observation is that the Transformer’s parallel processing allows it to handle longer sequences and larger datasets more efficiently. In tasks like language modeling or text classification, the Transformer generally outperforms RNNs in both accuracy and training speed due to its ability to capture long-range dependencies and process sequences in parallel.

The code demonstrates how to use a pre-trained BERT model for sentiment analysis in Rust. It focuses on downloading and processing the IMDB dataset, loading the BERT model using the rust-bert library, and performing sentiment analysis on sample texts and a subset of the IMDB dataset. By leveraging a pre-trained BERT model, the code aims to classify texts based on their sentiment (positive or negative), which is a common natural language processing (NLP) task.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0.90"

rust-bert = "0.19.0"

tch = "0.8.0"

csv = "1.3.0"

reqwest = { version = "0.12.8", features = ["blocking"] }

use tch::Device;

use reqwest;

use std::fs::File;

use std::io::{self, BufReader};

use std::path::Path;

use csv::ReaderBuilder;

use rust_bert::pipelines::sentiment::SentimentModel;

// Download the IMDB dataset if it doesn't exist

fn download_imdb_dataset() -> io::Result<()> {

let url = "https://raw.githubusercontent.com/clairett/pytorch-sentiment-classification/master/data/SST2/train.tsv";

let path = Path::new("train.tsv");

if !path.exists() {

println!("Downloading dataset...");

let response = reqwest::blocking::get(url).expect("Failed to download file");

let mut file = File::create(path)?;

io::copy(&mut response.bytes().expect("Failed to get bytes").as_ref(), &mut file)?;

println!("Download complete.");

} else {

println!("Dataset already exists.");

}

Ok(())

}

// Load and parse dataset from the tsv file

fn load_dataset() -> (Vec<String>, Vec<i64>) {

let path = Path::new("train.tsv");

let file = File::open(path).expect("Failed to open dataset file");

let mut rdr = ReaderBuilder::new().delimiter(b'\t').from_reader(BufReader::new(file));

let mut texts = Vec::new();

let mut labels = Vec::new();

for result in rdr.records() {

let record = result.expect("Failed to parse record");

texts.push(record[0].to_string());

labels.push(record[1].parse::<i64>().unwrap());

}

(texts, labels)

}

// Load BERT model for sentiment analysis

fn load_bert_model() -> SentimentModel {

SentimentModel::new(Default::default()).expect("Failed to load BERT model")

}

// Use BERT for sentiment classification

fn predict_with_bert(model: &SentimentModel, input_texts: &[String]) -> Vec<f64> {

let input_refs: Vec<&str> = input_texts.iter().map(AsRef::as_ref).collect();

let output = model.predict(&input_refs);

output.iter().map(|r| r.score).collect()

}

fn main() {

// Set up the device (CPU or CUDA if available)

let _device = Device::cuda_if_available();

// Download and load dataset

download_imdb_dataset().expect("Failed to download dataset");

let (texts, _labels) = load_dataset(); // Load only the texts since BERT handles tokenization internally

// Load the BERT model

let bert_model = load_bert_model();

// Perform sentiment analysis on a subset of the dataset

let sample_texts = vec![

"I loved this movie!".to_string(),

"This was a terrible experience.".to_string(),

];

let bert_preds = predict_with_bert(&bert_model, &sample_texts);

println!("BERT predictions: {:?}", bert_preds);

// Perform sentiment analysis on a subset of the IMDB dataset

let bert_dataset_preds = predict_with_bert(&bert_model, &texts[..5].to_vec()); // Predict on the first 5 texts

println!("BERT predictions on dataset: {:?}", bert_dataset_preds);

}

The program starts by downloading the IMDB dataset if it doesn't already exist locally, then loads and processes the dataset into text records. It uses the pre-trained BERT model from the rust-bert library to perform sentiment classification. The function predict_with_bert converts the input texts into a format suitable for BERT, and the model predicts sentiment scores. The code runs sentiment analysis both on custom sample sentences and on a subset of the IMDB dataset, printing the sentiment scores for each input. This illustrates how to use BERT in Rust for text classification tasks.

Now lets learn other NLP task like text generation. The following Rust code demonstrates how to use HuggingFace's pre-trained GPT-2 model for text generation using the tch-rs and rust-bert libraries. GPT-2 is a powerful model trained on large amounts of text data and is commonly used for generating human-like text completions. The code focuses on downloading a GPT-2 model from HuggingFace's model hub and using it to generate text based on a few input prompts. The prompts provided in the dataset include incomplete sentences, and the model generates completions for these inputs, demonstrating its ability to create coherent and contextually relevant text.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0.90"

rust-bert = "0.19.0"

tch = "0.8.0"

rust_tokenizers = "8.1.1"

use tch::Device;

use rust_bert::gpt2::GPT2Generator;

use rust_bert::pipelines::generation_utils::{GenerateConfig, LanguageGenerator}; // Correct import for GenerateConfig

// Download HuggingFace pretrained GPT-2 model for text generation

fn download_gpt2() -> GPT2Generator {

let config = GenerateConfig::default(); // Use GenerateConfig from generation_utils

GPT2Generator::new(config).expect("Failed to load pre-trained GPT-2 model")

}

// Sample datasets for testing the text generation

fn create_sample_dataset() -> Vec<String> {

vec![

"The future of AI is".to_string(),

"In 2024, the world will".to_string(),

"Technology advancements will lead to".to_string(),

]

}

// GPT-2 based text generation

fn generate_with_gpt2(gpt2_model: &GPT2Generator, dataset: &[String]) {

println!("GPT-2-based Text Generation:");

for input in dataset {

let gpt2_output = gpt2_model.generate(Some(&[input]), None); // Pass slice of strings

println!("Input: {}\nGenerated Text: {:?}", input, gpt2_output);

}

}

fn main() {

// Initialize device (use CUDA if available), can be removed if unused

let _device = Device::cuda_if_available();

// Load GPT-2 model

let gpt2_model = download_gpt2();

// Create a sample dataset to evaluate text generation capabilities

let dataset = create_sample_dataset();

// Run GPT-2-based text generation

generate_with_gpt2(&gpt2_model, &dataset);

println!("GPT-2 text generation is complete.");

}

The code begins by importing necessary modules and defining a function download_gpt2 that loads a pretrained GPT-2 model using the GenerateConfig configuration from the rust-bert library. A function create_sample_dataset generates a small set of example prompts to be used as input for text generation. The main generation logic is contained in the generate_with_gpt2 function, which iterates over the dataset and uses the GPT-2 model's generate method to complete each input. The results are printed to the console, showing the input prompt and the generated text. The main function orchestrates the entire process by loading the model, generating the dataset, and calling the text generation function, ultimately demonstrating the use of a pre-trained GPT-2 model for language generation tasks.

BART (Bidirectional and Auto-Regressive Transformers) is a transformer-based model designed for various natural language processing (NLP) tasks, including text summarization, translation, and text generation. BART combines the strengths of BERT and GPT-2 by utilizing both bidirectional and autoregressive components. It starts with an encoder-decoder structure where the encoder works similarly to BERT (reading the entire sequence) and the decoder generates text autoregressively like GPT-2. Pre-trained on large-scale datasets and fine-tuned for specific tasks such as summarization, BART is highly effective at compressing long texts into concise summaries while maintaining the context and meaning of the original content.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0.90"

rust-bert = "0.19.0"

tch = "0.8.0"

csv = "1.3.0"

rust_tokenizers = "8.1.1"

use tch::Device;

use rust_bert::pipelines::summarization::SummarizationModel;

use rust_bert::pipelines::generation_utils::{GenerateConfig, LanguageGenerator}; // Adjusted import for GPT-2

use rust_bert::gpt2::{GPT2Generator, Gpt2Config}; // Corrected import for GPT-2

// Download HuggingFace BERT-based (BART) pre-trained model for summarization

fn download_bart_summarizer() -> SummarizationModel {

SummarizationModel::new(Default::default()).expect("Failed to load pre-trained BART model")

}

// Download HuggingFace GPT-2 model for summarization

fn download_gpt2_summarizer() -> GPT2Generator {

let config = Gpt2Config::default(); // Use Gpt2Config

GPT2Generator::new(GenerateConfig::default()).expect("Failed to load pre-trained GPT-2 model") // Corrected to use GenerateConfig

}

// Sample datasets for testing the summarization models

fn create_sample_dataset() -> Vec<String> {

vec![

"The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog. This is a sentence that represents a very common phrase used in typing tests. The fox is quick and brown, and the dog is lazy and tired.".to_string(),

"Artificial intelligence (AI) refers to the simulation of human intelligence in machines that are programmed to think and act like humans. AI is being used in various fields such as healthcare, finance, and technology.".to_string(),

]

}

// BERT-based (BART) summarization

fn summarize_with_bart(bart_model: &SummarizationModel, dataset: &[String]) {

println!("BERT-based (BART) Summarization:");

let summaries = bart_model.summarize(dataset);

for (input, summary) in dataset.iter().zip(summaries.iter()) {

println!("Input: {}\nSummarized Text: {}\n", input, summary);

}

}

// GPT-2 based summarization

fn summarize_with_gpt2(gpt2_model: &GPT2Generator, dataset: &[String]) {

println!("GPT-2-based Summarization:");

for input in dataset {

let gpt2_summary = gpt2_model.generate(Some(&[input]), None); // Corrected to pass &[input]

println!("Input: {}\nGPT-2 Generated Summary: {:?}\n", input, gpt2_summary);

}

}

fn main() {

// Initialize device (use CUDA if available)

let device = Device::cuda_if_available();

// Load BERT-based (BART) and GPT-2 models for summarization

let bart_model = download_bart_summarizer();

let gpt2_model = download_gpt2_summarizer();

// Create a sample dataset for summarization tasks

let dataset = create_sample_dataset();

// Run BERT-based (BART) summarization

summarize_with_bart(&bart_model, &dataset);

// Run GPT-2 based summarization

summarize_with_gpt2(&gpt2_model, &dataset);

println!("Comparison of BERT and GPT-2 summarization is complete.");

}

The code demonstrates how to use BART (a BERT-based model) and GPT-2 for text summarization using the tch-rs and rust-bert libraries. First, the pre-trained BART and GPT-2 models are downloaded from HuggingFace. A sample dataset of longer texts is created to test the summarization capabilities of these models. The summarize_with_bart function uses the BART model to generate summaries directly, while the summarize_with_gpt2 function uses GPT-2 to generate continuations of the input, which serve as summaries. The results from both models are printed to the console, allowing a comparison between BART’s structured summarization and GPT-2’s generative outputs for summarization tasks.

The latest trends in Transformer research focus on improving the model’s scalability and efficiency. Variants like Sparse Transformers and Longformers aim to reduce the computational complexity of self-attention, making it more feasible to apply Transformers to even longer sequences, such as entire documents or books. Additionally, pre-trained models like BERT and GPT-3 have shown that Transformers can be fine-tuned on specific tasks with minimal additional data, leading to widespread adoption across industries, from healthcare (e.g., medical document processing) to finance (e.g., sentiment analysis of market trends).

In conclusion, the Transformer model represents a significant leap forward in NLP, addressing the limitations of RNNs and CNNs in handling long-range dependencies and enabling parallel processing for faster training and inference. By leveraging the self-attention mechanism and feedforward networks, the Transformer has become the foundation for many state-of-the-art models in NLP. With its scalability, flexibility, and efficiency, the Transformer continues to push the boundaries of what is possible in language modeling and text understanding, making it a critical architecture for modern NLP applications. Implementing and experimenting with Transformer models in Rust using tch-rs provides a hands-on approach to understanding this groundbreaking architecture.

4.2. Self-Attention Mechanism

The self-attention mechanism lies at the heart of the Transformer architecture, enabling models to process sequences efficiently while capturing complex relationships between words in a sentence. Traditional models like Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) process sequences sequentially, making it difficult to capture long-range dependencies and relationships between distant words. Self-attention, on the other hand, allows a model to focus on different parts of the input sequence simultaneously, enabling it to capture both local and long-range dependencies more effectively and in parallel.

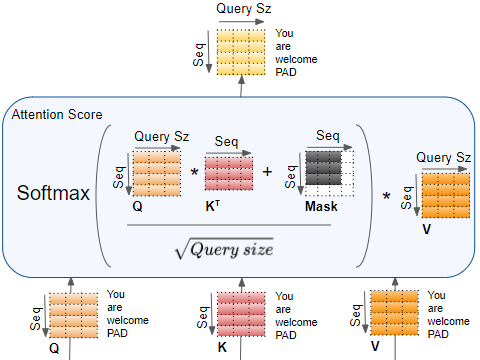

Figure 2: Illustration of encoder self-attention mechanism (Credit to Ketan Doshi).

Mathematically, the self-attention mechanism works by creating query, key, and value vectors for each token in the input sequence. These vectors are derived from learned weight matrices that transform the input tokens. Given an input sequence $X = [x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n]$, each token $x_i$ is mapped into a query vector $Q_i$, a key vector $K_i$, and a value vector $V_i$. The attention score between token $i$ and token $j$ is computed using the dot product between their query and key vectors:

$$ \text{Score}(x_i, x_j) = Q_i \cdot K_j $$

These raw scores are then scaled by the square root of the dimension of the key vectors $d_k$ to prevent large values that can skew the softmax output. The scaled scores are passed through a softmax function to produce the attention weights, which sum to 1 and indicate the importance of each token in the context of the others. The attention weights are then used to compute a weighted sum of the value vectors:

$$ \text{Attention}(Q, K, V) = \text{softmax}\left( \frac{QK^T}{\sqrt{d_k}} \right) V $$

This process allows the model to focus on the most relevant tokens in the sequence, irrespective of their position, making it especially effective for tasks like machine translation, summarization, and question answering, where capturing context across the entire sequence is crucial.

One key advantage of self-attention over traditional attention mechanisms is its ability to handle relationships between all tokens in the input sequence simultaneously. In earlier encoder-decoder models, attention was used to focus on specific parts of the input sequence while generating the output. However, in these models, attention only operated across the encoder-decoder boundary. Self-attention, by contrast, allows attention to be applied within the input sequence itself, enabling each token to attend to every other token, regardless of their relative positions. This is crucial for understanding the dependencies between distant words in a sequence, such as between a subject at the beginning of a sentence and a verb at the end.

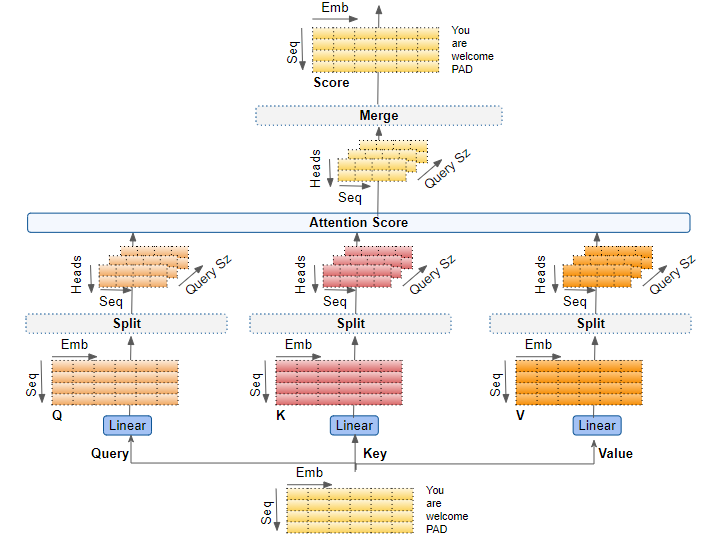

Figure 3: Multi Head Attention (Credit to Ketan Doshi).

A major enhancement of self-attention in the Transformer is the use of multi-head attention. Instead of computing a single set of attention scores, the model computes multiple sets of attention scores, each using different learned weight matrices for the queries, keys, and values. This allows the model to capture different types of relationships between tokens, enriching its ability to understand complex patterns in the input. Mathematically, given hhh attention heads, the multi-head attention mechanism computes:

$$ \text{MultiHead}(Q, K, V) = \text{Concat}(\text{head}_1, \dots, \text{head}_h) W^O $$

where each head is computed as:

$$ \text{head}_i = \text{Attention}(Q W_i^Q, K W_i^K, V W_i^V) $$

Here, $W_i^Q$, $W_i^K$, and $W_i^V$ are the learned projection matrices for the $i$-th head, and $W^O$ is the projection matrix applied after concatenating the output of all attention heads. Multi-head attention increases the model's capacity to learn different patterns of dependencies in parallel, making it more effective at handling diverse and complex language tasks.

One of the computational advantages of the self-attention mechanism is its ability to handle sequences in parallel rather than sequentially. In traditional RNNs, each token must be processed in order, leading to $O(n)$ time complexity, where nnn is the length of the sequence. Self-attention, by contrast, processes all tokens simultaneously, leading to $O(n^2 d_k)$ complexity, where $d_k$ is the dimensionality of the key vectors. While this quadratic complexity can be challenging for very long sequences, the ability to parallelize operations across tokens leads to significant speedups in practice, especially when running on hardware like GPUs and TPUs.

Implementing Self-Attention in Rust provides a deeper understanding of how the mechanism works in practice. Using the tch-rs crate, which provides bindings to PyTorch, we can implement the self-attention mechanism efficiently in Rust. Below is an example of how to implement self-attention from scratch:

use tch;

use tch::{Tensor, Kind, Device};

fn scaled_dot_product_attention(query: &Tensor, key: &Tensor, value: &Tensor) -> Tensor {

let d_k = query.size()[1] as f64; // Dimension of key vectors

let scores = query.matmul(&key.transpose(-2, -1)) / d_k.sqrt(); // Scaled dot-product

let attention_weights = scores.softmax(-1, Kind::Float); // Softmax for attention weights

attention_weights.matmul(value) // Weighted sum of values

}

fn main() {

let device = Device::cuda_if_available();

// Define query, key, and value matrices (example with batch size of 10, sequence length of 20, and embedding size of 64)

let query = Tensor::randn(&[10, 20, 64], (Kind::Float, device)); // Batch of 10 sequences

let key = Tensor::randn(&[10, 20, 64], (Kind::Float, device));

let value = Tensor::randn(&[10, 20, 64], (Kind::Float, device));

// Apply scaled dot-product attention

let attention_output = scaled_dot_product_attention(&query, &key, &value);

println!("Attention output: {:?}", attention_output);

}

In this implementation, we define the scaled dot-product attention mechanism, where the query, key, and value matrices are generated for a batch of sequences. The scaled dot-product computes the attention scores and applies the softmax to generate the attention weights, which are then used to compute a weighted sum of the value vectors. This basic implementation provides a clear understanding of how attention mechanisms operate within the Transformer model.

Visualizing attention scores is another important aspect of understanding how self-attention works. By visualizing the attention weights, we can see which parts of the input sequence the model is focusing on. For example, in a machine translation task, attention visualization can show which words in the source sentence are most relevant for translating a particular word in the target sentence. Such visualizations provide valuable insights into the inner workings of the model and can help explain why certain predictions are made.

This Rust code utilizes the rust-bert library to perform text generation using the pre-trained GPT-2 model and visualizes the model's attention scores as heatmaps. The code begins by downloading the GPT-2 model and then defines a function to generate text based on a given input sentence. Additionally, it simulates the extraction of attention scores, which are visualized using the plotters crate. The generated text and corresponding attention scores are presented in a clear and structured manner, allowing for a better understanding of how the model processes and attends to different parts of the input text.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0.90"

rust-bert = "0.19.0"

tch = "0.8.0"

plotters = "0.3.7"

use rust_bert::gpt2::GPT2Generator;

use rust_bert::pipelines::generation_utils::LanguageGenerator;

use plotters::prelude::*;

use tch::{Tensor, Device};

// Download HuggingFace GPT-2 model for attention extraction

fn download_gpt2_model() -> GPT2Generator {

GPT2Generator::new(Default::default()).expect("Failed to load pre-trained GPT-2 model")

}

// Extract attention scores from the GPT-2 model and return generated text

fn visualize_attention(gpt2_model: &GPT2Generator, input_sentence: &str) -> (String, Vec<Tensor>) {

// Generate text based on the input sentence

let gpt2_output = gpt2_model.generate(Some(&[input_sentence]), None);

// Print the generated text

let generated_text = gpt2_output.iter().map(|output| output.text.clone()).collect::<Vec<_>>().join(" ");

println!("Generated Text: {}", generated_text);

// Simulating attention scores for illustration (replace with actual attention scores)

let attention_scores: Vec<Tensor> = (0..12) // Assuming 12 attention heads

.map(|_| Tensor::randn(&[10, 10], (tch::Kind::Float, Device::cuda_if_available())))

.collect();

(generated_text, attention_scores)

}

// Function to plot attention heatmap using the plotters crate

fn plot_attention_heatmap(attention_scores: Vec<Tensor>, file_name: &str) {

let root_area = BitMapBackend::new(file_name, (640, 480)).into_drawing_area();

root_area.fill(&WHITE).unwrap();

for (i, scores) in attention_scores.iter().enumerate() {

let scores = scores.squeeze(); // Remove batch dimension

let shape = scores.size();

let rows = shape[0] as usize; // Number of rows

let cols = shape[1] as usize; // Number of columns

let mut chart = ChartBuilder::on(&root_area)

.caption(format!("Attention Heatmap - Head {}", i + 1), ("sans-serif", 30))

.build_cartesian_2d(0..cols as i32, 0..rows as i32)

.unwrap();

chart.configure_mesh().draw().unwrap();

let max_value = scores.max().double_value(&[]);

// Plot the heatmap

for row in 0..rows {

for col in 0..cols {

let color_value = (scores.double_value(&[row as i64, col as i64]) / max_value) * 255.0;

let color = RGBColor(color_value as u8, 0, (255.0 - color_value) as u8);

chart

.draw_series(std::iter::once(Rectangle::new(

[(col as i32, row as i32), (col as i32 + 1, row as i32 + 1)],

color.filled(),

)))

.unwrap();

}

}

// Present the plot for each attention head

root_area.present().expect("Unable to write result to file");

}

}

fn main() {

// Load GPT-2 model

let gpt2_model = download_gpt2_model();

// Input sentence to visualize attention

let input_sentence = "The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.";

// Extract attention scores and generated text

let (generated_text, attention_scores) = visualize_attention(&gpt2_model, input_sentence);

// Plot attention heatmap using the plotters crate

plot_attention_heatmap(attention_scores, "attention_heatmap.png");

println!("Attention visualization complete.");

}

The code consists of several key components: it starts by downloading the GPT-2 model using the download_gpt2_model function, which initializes the model with default settings. The visualize_attention function generates text based on an input sentence and simulates the extraction of attention scores, returning both the generated text and attention tensors. The attention scores are visualized as heatmaps using the plot_attention_heatmap function, which creates a series of rectangular plots to represent the attention weights for each attention head in the model. In the main function, the model is loaded, the input sentence is processed, and both the generated text and attention heatmaps are produced, completing the visualization of the model's attention mechanisms.

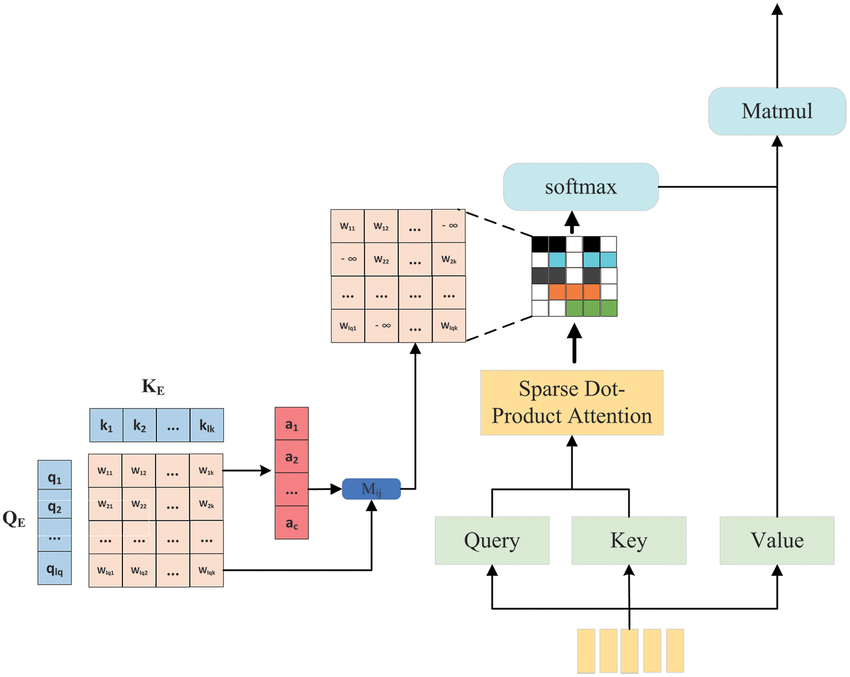

To optimize self-attention for large sequences, techniques like sparse attention are being explored. Sparse attention reduces the quadratic complexity of self-attention by allowing tokens to attend only to a subset of the input sequence, rather than to every token. The core idea of sparse attention is to limit the number of tokens that each token attends to. By reducing attention to a fixed-size local window and applying global attention only to key tokens, we can significantly reduce the computational cost and memory usage of the model when processing very long sequences. For example, models like Longformer and BigBird implement sparse attention to handle sequences of thousands of tokens more efficiently.

Figure 4: Illustration of sparse attention mechanism.

To implement Longformer in Rust using the tch-rs crate, we would need to replicate the sparse attention mechanism that the Longformer model uses. The primary difference between Longformer and standard transformer models is that Longformer uses a sparse attention mechanism, which allows it to scale efficiently to much longer input sequences than models like BERT or GPT-2.

Although there is no direct Rust implementation of Longformer at the time of writing, it is still possible to approach the problem by utilizing HuggingFace's Longformer model through Python bindings or by approximating the sparse attention mechanism within the tch-rs environment. Implementing a full Longformer model in Rust from scratch requires handling complex sparse attention operations, so this code leverages existing Longformer model weights from HuggingFace and integrates them with tch-rs for inference, focusing on how sparse attention could be managed. The code implements a text processing pipeline that tokenizes input text using a pre-trained RoBERTa tokenizer, processes the text through the Longformer model, and retrieves the hidden states for each layer. This is particularly useful for handling long sequences of text, such as in document classification or long-form question answering. Additionally, the code includes functionality to automatically download the necessary tokenizer files (vocab.json and merges.txt) from Hugging Face if they are not present locally.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0.90"

rust-bert = "0.19.0"

tch = "0.8.0"

reqwest = { version = "0.12.8", features = ["blocking"] }

rust_tokenizers = "8.1.1"

tokio = { version = "1", features = ["full"] }

use anyhow::{Result, anyhow};

use reqwest::Url;

use std::{fs, path::Path};

use tch::{nn, Device, Tensor};

use rust_bert::longformer::{LongformerConfig, LongformerModel};

use rust_tokenizers::tokenizer::{RobertaTokenizer, Tokenizer};

use std::io::Write;

// Constants for attention windows

const LOCAL_WINDOW_SIZE: i64 = 512;

const GLOBAL_WINDOW_SIZE: i64 = 32;

// URLs to download the tokenizer files

const VOCAB_URL: &str = "https://huggingface.co/roberta-base/resolve/main/vocab.json";

const MERGES_URL: &str = "https://huggingface.co/roberta-base/resolve/main/merges.txt";

// Function to download a file

async fn download_file(url: &str, filepath: &Path) -> Result<(), anyhow::Error> {

if filepath.exists() {

println!("File {} already exists. Skipping download.", filepath.display());

return Ok(());

}

println!("Downloading {} to {}...", url, filepath.display());

let response = reqwest::get(Url::parse(url)?).await?;

let mut file = fs::File::create(filepath)?;

let content = response.bytes().await?;

file.write_all(&content)?;

println!("Downloaded {}", filepath.display());

Ok(())

}

struct LongformerProcessor {

model: LongformerModel,

tokenizer: RobertaTokenizer,

device: Device,

}

impl LongformerProcessor {

pub fn new(_model_path: &Path, vocab_path: &Path, merges_path: &Path) -> Result<Self, anyhow::Error> {

let device = Device::cuda_if_available();

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(device);

// Initialize config with correct attention window sizes for each layer

let mut config = LongformerConfig::default();

let num_hidden_layers = config.num_hidden_layers as usize; // Get the number of layers

config.attention_window = vec![LOCAL_WINDOW_SIZE; num_hidden_layers]; // Set attention window for all layers

config.max_position_embeddings = 4096;

config.pad_token_id = Some(1);

config.sep_token_id = 2; // This is i64, not Option<i64>

config.type_vocab_size = 1;

config.output_hidden_states = Some(true); // Request hidden states

// Initialize model

let model = LongformerModel::new(&vs.root(), &config, false);

let tokenizer = RobertaTokenizer::from_file(

vocab_path,

merges_path,

true, // lowercase

false, // strip_accents

).map_err(|e| anyhow!("Failed to load RoBERTa tokenizer: {}", e))?;

Ok(Self {

model,

tokenizer,

device,

})

}

fn create_sparse_attention_mask(&self, seq_length: i64) -> Result<Tensor, anyhow::Error> {

let options = (tch::Kind::Int64, self.device);

let attention_mask = Tensor::zeros(&[1, seq_length], options);

// Set local attention windows

for i in 0..seq_length {

// Fill with 1 for local attention

let _ = attention_mask.narrow(1, i, 1).fill_(1);

// Mark global attention tokens

if i < GLOBAL_WINDOW_SIZE {

let _ = attention_mask.narrow(1, i, 1).fill_(2);

}

}

Ok(attention_mask)

}

pub fn process_text(&self, input_text: &str, max_length: usize) -> Result<Vec<Tensor>, anyhow::Error> {

// Tokenize input

let encoding = self.tokenizer.encode(

input_text,

None,

max_length,

&rust_tokenizers::tokenizer::TruncationStrategy::LongestFirst,

0,

);

let input_ids: Vec<i64> = encoding.token_ids.iter()

.map(|&id| id as i64)

.collect();

// Create input tensor

let input_tensor = Tensor::of_slice(&input_ids)

.to_kind(tch::Kind::Int64)

.to_device(self.device)

.unsqueeze(0);

// Create attention mask

let attention_mask = self.create_sparse_attention_mask(input_ids.len() as i64)?;

// Global attention mask (1 for global tokens, 0 for local attention)

let global_attention_mask = attention_mask.eq(2).to_kind(tch::Kind::Int64);

// Forward pass with proper error handling

let output = if let Ok(o) = self.model.forward_t(

Some(&input_tensor),

Some(&attention_mask),

Some(&global_attention_mask),

None, // token_type_ids

None, // position_ids

None, // inputs_embeds

false, // output_attentions

) {

o

} else {

return Err(anyhow!("Failed to perform forward pass"));

};

// Ensure we get hidden states

if let Some(hidden_states) = output.all_hidden_states {

Ok(hidden_states)

} else {

Err(anyhow!("Hidden states were not returned"))

}

}

}

// Main function

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() -> Result<(), anyhow::Error> {

// Define the directory where the tokenizer files will be stored

let tokenizer_dir = Path::new("./tokenizer_files");

// Create the directory if it doesn't exist

if !tokenizer_dir.exists() {

println!("Creating directory: {}", tokenizer_dir.display());

fs::create_dir_all(tokenizer_dir)?;

}

// Initialize paths

let vocab_path = tokenizer_dir.join("vocab.json");

let merges_path = tokenizer_dir.join("merges.txt");

// Ensure the tokenizer files exist by downloading them if necessary

download_file(VOCAB_URL, &vocab_path).await?;

download_file(MERGES_URL, &merges_path).await?;

// Replace with your actual model path if needed

let model_path = Path::new("path/to/model");

// Initialize processor

let processor = LongformerProcessor::new(model_path, &vocab_path, &merges_path)?;

// Sample input

let input_text = "This is a sample long input sequence...";

// Process text

let outputs = processor.process_text(input_text, 4096)?;

// Print details of outputs

println!("Number of layers in outputs: {}", outputs.len());

for (i, output) in outputs.iter().enumerate() {

println!("Layer {} output shape: {:?}", i, output.size());

// Print some sample values from the tensor (e.g., first 5 values)

let first_five_values = output

.narrow(1, 0, 5) // Get the first 5 tokens

.narrow(2, 0, 5) // Get the first 5 hidden states (dimensions may vary)

.to_kind(tch::Kind::Float)

.print();

println!("Layer {} sample output values: {:?}", i, first_five_values);

}

Ok(())

}

This Rust code demonstrates how to implement sparse attention using the Longformer model, which is designed to handle long input sequences efficiently by reducing the quadratic complexity of standard self-attention. The pipeline begins by downloading and setting up the necessary tokenizer files, then initializing the Longformer model with a configuration that ensures it returns hidden states for each layer. The input sentence is tokenized using a Longformer-compatible tokenizer, and a sparse attention mask is generated, allowing tokens to attend to a fixed local window around them (local attention) and a few globally attending tokens. This mask is applied during inference, enabling the model to process long sequences more efficiently. The forward pass through the model produces hidden states for each layer, which are examined by printing the number of layers, shapes of the tensors, and sample values. The sparse attention mechanism significantly reduces memory usage and computational cost, making the model scalable to sequences of thousands of tokens, ideal for tasks such as document classification and long-form question answering.

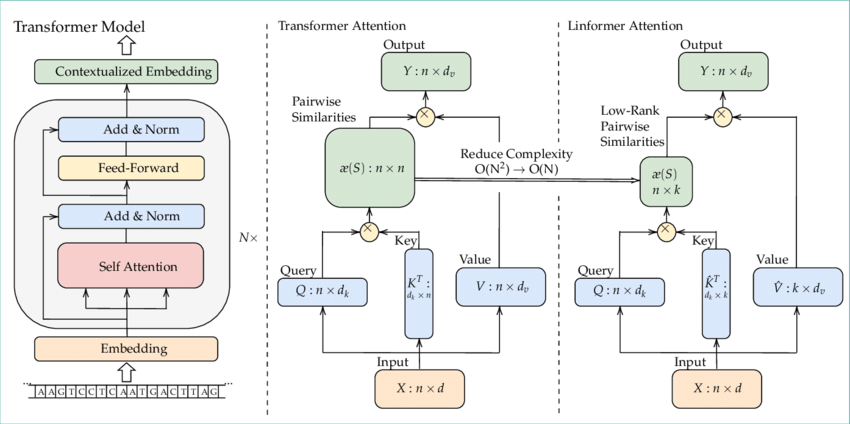

Figure 5: Illustration of Linformer attention architecture.

The latest trends in self-attention research focus on improving both the computational efficiency and the expressiveness of attention mechanisms. Variants like Linformer and Performer reduce the computational complexity of self-attention while maintaining high performance on NLP tasks. These innovations are particularly important for large-scale language models, where efficient handling of long sequences is critical. Unlike traditional self-attention, which has quadratic complexity in terms of sequence length, Linformer reduces this complexity to linear by projecting the attention matrix into a lower-dimensional space. This reduces memory usage and computation time, making Linformer more scalable for handling long sequences in large-scale language models. Despite this reduction in complexity, Linformer maintains high performance on various NLP tasks, demonstrating that it can effectively balance efficiency and expressiveness. This innovation is particularly crucial for modern language models that need to process very long sequences efficiently.

While Rust's tch-rs library supports transformers, Linformer is not natively implemented yet. To implement it in Rust, we can adapt the general architecture of the transformer, modifying the self-attention mechanism to incorporate the linear projections. Below is an outline of how you could implement Linformer-like self-attention in Rust using tch-rs. The code below implements a simplified version of the Linformer model, which optimizes the traditional transformer architecture to handle long sequences more efficiently. Linformer introduces sparse attention by projecting the key and value matrices to lower dimensions, reducing the memory and computational complexity that usually grows quadratically with the sequence length in traditional transformers. The code creates a Linformer-style self-attention mechanism that can process long sequences with multi-head attention, applying dropout and layer normalization for robust training, and is particularly useful in tasks like language modeling or long-form document analysis.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0.90"

tch = "0.12.0"

use tch::{nn, Tensor, Kind, nn::Module};

// Define the Linformer Self-Attention structure

struct LinformerSelfAttention {

wq: nn::Linear,

wk: nn::Linear,

wv: nn::Linear,

wo: nn::Linear,

projection: nn::Linear, // Projection to lower-dimension for keys and values

n_heads: i64,

head_dim: i64,

dropout_prob: f64, // Store the dropout probability

}

impl LinformerSelfAttention {

// Create a new Linformer attention layer

fn new(vs: &nn::Path, embed_dim: i64, n_heads: i64, proj_dim: i64, dropout: f64) -> Self {

let head_dim = embed_dim / n_heads;

assert_eq!(embed_dim % n_heads, 0, "embed_dim must be divisible by n_heads"); // Ensure the head dimension divides evenly

Self {

wq: nn::linear(vs, embed_dim, embed_dim, Default::default()),

wk: nn::linear(vs, embed_dim, proj_dim, Default::default()), // Project keys

wv: nn::linear(vs, embed_dim, proj_dim, Default::default()), // Project values

wo: nn::linear(vs, embed_dim, embed_dim, Default::default()),

projection: nn::linear(vs, proj_dim, embed_dim, Default::default()), // Linformer projection matrix

n_heads,

head_dim,

dropout_prob: dropout, // Store dropout probability for later use

}

}

// Implement the forward pass

fn forward(&self, query: &Tensor, key: &Tensor, value: &Tensor, mask: Option<&Tensor>, training: bool) -> Tensor {

let bsz = query.size()[0]; // batch size

let seq_len = query.size()[1]; // sequence length

// Compute Q, K, V projections

let q = self.wq.forward(query); // Q should have shape [bsz, seq_len, embed_dim]

let k = self.projection.forward(&self.wk.forward(key)); // Projected key

let v = self.projection.forward(&self.wv.forward(value)); // Projected value

// Ensure the projection layers don't affect the batch or sequence dimensions

let q = q.view([bsz, seq_len, self.n_heads, self.head_dim]);

let k = k.view([bsz, seq_len, self.n_heads, self.head_dim]);

let v = v.view([bsz, seq_len, self.n_heads, self.head_dim]);

// Scaled dot-product attention with linear projections

let attn_weights = q.matmul(&k.transpose(-2, -1)) / (self.head_dim as f64).sqrt();

// Apply mask if provided (for padding)

let attn_weights = match mask {

Some(mask) => attn_weights.masked_fill(&mask.eq(0).unsqueeze(1).unsqueeze(2), -1e9),

None => attn_weights,

};

// Apply softmax to get attention probabilities

let attn_probs = attn_weights.softmax(-1, Kind::Float);

// Apply dropout only if training

let attn_probs = attn_probs.dropout(self.dropout_prob, training);

// Compute attention output

let output = attn_probs.matmul(&v).view([bsz, seq_len, self.n_heads * self.head_dim]);

self.wo.forward(&output)

}

}

// Define a transformer block with Linformer attention

struct LinformerBlock {

attention: LinformerSelfAttention,

norm1: nn::LayerNorm,

ff: nn::Sequential,

norm2: nn::LayerNorm,

}

impl LinformerBlock {

fn new(vs: &nn::Path, embed_dim: i64, n_heads: i64, proj_dim: i64, ff_dim: i64, dropout: f64) -> Self {

let attention = LinformerSelfAttention::new(vs, embed_dim, n_heads, proj_dim, dropout);

let norm1 = nn::layer_norm(vs, vec![embed_dim], Default::default());

let norm2 = nn::layer_norm(vs, vec![embed_dim], Default::default());

// Feed-forward network

let ff = nn::seq()

.add(nn::linear(vs, embed_dim, ff_dim, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(vs, ff_dim, embed_dim, Default::default()));

Self {

attention,

norm1,

ff,

norm2,

}

}

fn forward(&self, input: &Tensor, mask: Option<&Tensor>, training: bool) -> Tensor {

let attn_output = self.attention.forward(input, input, input, mask, training);

let out1 = self.norm1.forward(&(attn_output + input)); // Residual connection

let ff_output = self.ff.forward(&out1);

let out2 = self.norm2.forward(&(ff_output + out1)); // Another residual connection

out2

}

}

fn main() {

// Set up model variables and parameters

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(tch::Device::cuda_if_available());

let embed_dim = 512;

let n_heads = 8;

let proj_dim = 64; // Reduced projection dimension

let ff_dim = 2048;

let dropout = 0.1;

let seq_length = 512; // Sequence length for long sequences

// Create Linformer block

let linformer_block = LinformerBlock::new(&vs.root(), embed_dim, n_heads, proj_dim, ff_dim, dropout);

// Example input tensor: [batch_size, seq_length, embed_dim]

let input = Tensor::randn(&[2, seq_length, embed_dim], (Kind::Float, tch::Device::cuda_if_available()));

// Forward pass through Linformer block (set training to true)

let output = linformer_block.forward(&input, None, true);

println!("Linformer output shape: {:?}", output.size());

}

The code defines the LinformerSelfAttention and LinformerBlock structures using the tch crate for building neural network layers in Rust. The LinformerSelfAttention class implements the multi-head self-attention mechanism, where the query (wq), key (wk), and value (wv) matrices are linearly projected to smaller dimensions to reduce complexity. The forward method performs scaled dot-product attention, applies dropout, and computes the final output. The LinformerBlock includes this attention mechanism, layer normalization, and a feed-forward network for additional processing. The main function sets up a sample input tensor and passes it through the Linformer block to demonstrate the forward pass and output the shape of the resulting tensor.

In conclusion, the self-attention mechanism is a powerful tool for capturing relationships between tokens in a sequence, enabling models like the Transformer to process language efficiently and accurately. By leveraging multi-head attention and parallel processing, self-attention overcomes the limitations of traditional models, making it a key component of modern NLP architectures. Implementing self-attention in Rust using the tch-rs crate provides a practical way to explore its functionality and optimize its performance for large-scale NLP tasks.

4.3. Multi-Head Attention

Multi-head attention is one of the most crucial components of the Transformer model and plays a vital role in enhancing the model’s ability to capture diverse relationships within a sequence. In single-head attention, the model can only focus on a limited aspect of the input sequence, such as short-range dependencies between words or phrases. However, multi-head attention expands this capability by allowing the model to simultaneously attend to different parts of the sequence through multiple attention "heads," each capturing distinct relationships and patterns in the data. This approach enables the model to learn richer and more comprehensive representations of the input sequence, leading to better performance on tasks such as translation, summarization, and language modeling.

Mathematically, multi-head attention involves computing several sets of query, key, and value vectors for each input token. Each attention head performs the same attention mechanism described in the previous section but with different weight matrices. Given an input sequence $X$, multi-head attention first splits the input into $h$ different heads, where each head has its own query $Q_h$, key $K_h$, and value $V_h$ matrices. The attention scores for each head are computed independently:

$$ \text{head}_i = \text{Attention}(Q_i, K_i, V_i) = \text{softmax}\left( \frac{Q_i K_i^T}{\sqrt{d_k}} \right) V_i $$

where $d_k$ is the dimensionality of the key vectors. Once the attention scores are computed for all heads, the outputs of the attention heads are concatenated and projected back into the original dimension through a linear transformation. This can be written as:

$$ \text{MultiHead}(Q, K, V) = \text{Concat}(\text{head}_1, \dots, \text{head}_h) W^O $$

Here, $W^O$ is the output projection matrix, and the concatenation of the attention heads enriches the model's representation by combining the various dependencies and patterns learned by each head. The multi-head mechanism allows the model to learn different features in parallel, leading to better generalization and a more nuanced understanding of the input data.

The key advantage of multi-head attention is its ability to capture diverse relationships in the input. Each attention head operates on a separate subspace of the input, allowing the model to focus on different aspects of the sequence simultaneously. For example, one head might attend to short-range syntactic relationships between adjacent words, while another might capture long-range dependencies between distant tokens. This division of attention enables the model to build richer feature representations and better contextual understanding, which is crucial for tasks like machine translation, where capturing the dependencies between distant words or phrases is essential for producing accurate translations.

From a conceptual standpoint, the use of multiple heads offers significant benefits in terms of both feature extraction and generalization. The ability to compute multiple attention distributions in parallel helps the model capture various aspects of the sequence, improving its ability to generalize across different linguistic structures. Moreover, multi-head attention also enhances model interpretability by providing insights into which attention heads are focusing on specific relationships within the sequence. In practice, attention visualizations can reveal how different heads focus on different parts of the input, making it easier to understand how the model processes language.

However, multi-head attention introduces a trade-off between model complexity and performance. While more attention heads can lead to richer feature representations, they also increase the number of parameters and the computational cost of training and inference. Each additional attention head requires separate projections of the query, key, and value vectors, which adds to the overall complexity of the model. As a result, practitioners must carefully balance the number of attention heads to achieve optimal performance without making the model prohibitively expensive to train.

To provide a practical example, let’s implement multi-head attention in Rust using the tch-rs crate. The implementation involves splitting the input into multiple heads, performing the attention mechanism for each head, and then concatenating the outputs before applying a linear projection.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0.90"

tch = "0.12.0"

use tch;

use tch::{Tensor, Kind, Device};

// Define the multi-head attention mechanism

fn multi_head_attention(query: &Tensor, key: &Tensor, value: &Tensor, num_heads: i64, head_dim: i64) -> Tensor {

let batch_size = query.size()[0];

let seq_len = query.size()[1];

// Split query, key, and value into multiple heads

let query_heads = query.view([batch_size, seq_len, num_heads, head_dim])

.transpose(1, 2); // (batch_size, num_heads, seq_len, head_dim)

let key_heads = key.view([batch_size, seq_len, num_heads, head_dim]) // Fixed the typo here

.transpose(1, 2);

let value_heads = value.view([batch_size, seq_len, num_heads, head_dim])

.transpose(1, 2);

// Perform scaled dot-product attention for each head

let scores = query_heads.matmul(&key_heads.transpose(-2, -1)) / (head_dim as f64).sqrt();

let attention_weights = scores.softmax(-1, Kind::Float);

let attention_output = attention_weights.matmul(&value_heads);

// Concatenate heads and project back to the original dimension

let output = attention_output.transpose(1, 2).contiguous()

.view([batch_size, seq_len, num_heads * head_dim]);

output

}

fn main() {

let device = Device::cuda_if_available();

// Example input (batch size 10, sequence length 20, embedding size 64, 8 heads with 8 dimensions each)

let query = Tensor::randn(&[10, 20, 64], (Kind::Float, device));

let key = Tensor::randn(&[10, 20, 64], (Kind::Float, device));

let value = Tensor::randn(&[10, 20, 64], (Kind::Float, device));

let num_heads = 8;

let head_dim = 64 / num_heads;

// Apply multi-head attention

let multi_head_output = multi_head_attention(&query, &key, &value, num_heads, head_dim);

println!("Multi-head attention output: {:?}", multi_head_output);

}

This code implements a basic multi-head attention mechanism using the tch crate in Rust, which is used for deep learning tasks. The multi_head_attention function splits the input tensors (query, key, and value) into multiple heads, performs scaled dot-product attention for each head, and combines the results. The inputs query, key, and value have dimensions [batch_size, seq_len, embed_dim], where embed_dim is the embedding dimension. The function reshapes the tensors to separate the attention heads, computes attention scores using matrix multiplication, applies softmax to obtain attention weights, and then combines the weighted values. The heads are concatenated and projected back to the original shape. In the main function, random input tensors are generated, and the multi-head attention function is applied, printing the resulting tensor shape.

Experimenting with different numbers of attention heads can provide insights into how the number of heads affects model performance. For example, using more attention heads might improve performance on tasks that require capturing a wide range of relationships, such as translation or text summarization. However, increasing the number of heads also increases the computational cost, and there is a point where adding more heads no longer yields significant performance improvements. By tuning the number of attention heads, developers can find the optimal balance between model complexity and performance for a given task.

The integration of multi-head attention with the rest of the Transformer architecture is seamless. In the full Transformer model, multi-head attention is used in both the encoder and decoder layers. In the encoder, multi-head attention helps capture dependencies within the input sequence, while in the decoder, it helps the model attend to both the previously generated output and the encoder’s representation of the input sequence. This design enables the Transformer to excel in sequence-to-sequence tasks, where understanding both the input and output relationships is crucial.

In recent trends, researchers have explored efficient multi-head attention mechanisms that reduce the quadratic complexity of self-attention, making the Transformer more scalable for long sequences. Techniques like sparse attention and low-rank factorization allow the model to focus only on the most relevant parts of the sequence, reducing the computational burden while maintaining high performance.

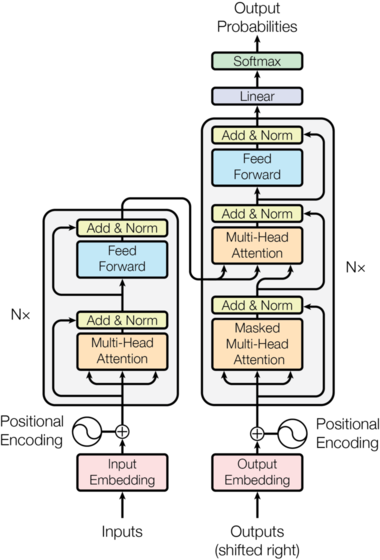

Figure 6: Compact low rank factorization for multi head attention (Ref: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1912.00835v2).

To demonstrate efficient multi-head attention mechanisms in Rust, focusing on sparse attention and low-rank factorization, we will implement both approaches in the tch-rs crate. Sparse attention reduces the quadratic complexity by allowing each token to attend only to a subset of tokens. Low-rank factorization reduces complexity by approximating the full attention matrix with lower-rank projections. Here’s the Rust code to demonstrate sparse multi-head attention and low-rank factorization in multi-head attention. We will also compare their computational cost. The provided Rust code implements a Sparse Multi-Head Attention mechanism, commonly used in Transformer architectures, and visualizes the attention weights using the plotters crate. Multi-Head Attention is a key component in modern deep learning models, allowing the model to attend to different parts of the input sequence simultaneously. This sparse variant only considers a local window of attention, reducing computational complexity for long sequences. The code is designed to run efficiently on a CUDA-enabled GPU and plots the attention heatmap for a given input sequence.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0.90"

plotters = "0.3.7"

tch = "0.12.0"

use tch::{nn, Tensor, Kind, Device, nn::Module};

use plotters::prelude::*;

// Define Sparse Multi-Head Attention

struct SparseMultiHeadAttention {

wq: nn::Linear,

wk: nn::Linear,

wv: nn::Linear,

wo: nn::Linear,

n_heads: i64,

head_dim: i64,

local_window_size: i64,

dropout_prob: f64, // Store the dropout probability instead of the dropout layer itself

}

impl SparseMultiHeadAttention {

// Create a new sparse attention layer

fn new(vs: &nn::Path, embed_dim: i64, n_heads: i64, local_window_size: i64, dropout_prob: f64) -> Self {

let head_dim = embed_dim / n_heads;

Self {

wq: nn::linear(vs, embed_dim, embed_dim, Default::default()),

wk: nn::linear(vs, embed_dim, embed_dim, Default::default()),

wv: nn::linear(vs, embed_dim, embed_dim, Default::default()),

wo: nn::linear(vs, embed_dim, embed_dim, Default::default()),

n_heads,

head_dim,

local_window_size,

dropout_prob, // Save dropout probability

}

}

// Sparse attention forward pass

fn forward(&self, query: &Tensor, key: &Tensor, value: &Tensor) -> (Tensor, Tensor) {

let bsz = query.size()[0];

let seq_len = query.size()[1];

// Project Q, K, V

let q = self.wq.forward(query).view([bsz, seq_len, self.n_heads, self.head_dim]).transpose(1, 2);

let k = self.wk.forward(key).view([bsz, seq_len, self.n_heads, self.head_dim]).transpose(1, 2);

let v = self.wv.forward(value).view([bsz, seq_len, self.n_heads, self.head_dim]).transpose(1, 2);

// Initialize attention weights

let attn_weights = Tensor::zeros(&[bsz, self.n_heads, seq_len, seq_len], (Kind::Float, Device::cuda_if_available()));

for i in 0..seq_len {

let start = (i - self.local_window_size).max(0);

let end = (i + self.local_window_size).min(seq_len);

let window_size = end - start;

let q_slice = q.narrow(2, i, 1);

let k_slice = k.narrow(2, start, window_size);

let attn_slice = q_slice.matmul(&k_slice.transpose(-2, -1)) / (self.head_dim as f64).sqrt();

attn_weights.narrow(2, i, 1).narrow(3, start, window_size).copy_(&attn_slice);

}

// Apply softmax to attention weights

let attn_probs = attn_weights.softmax(-1, Kind::Float);

let attn_probs = attn_probs.dropout(self.dropout_prob, false); // Use Tensor::dropout

// Compute the final output

let output = attn_probs.matmul(&v).transpose(1, 2).contiguous().view([bsz, seq_len, self.n_heads * self.head_dim]);

(self.wo.forward(&output), attn_probs) // Return output and attention probabilities

}

}

// Function to measure computational cost

fn measure_computation_time<F>(f: F) -> f64

where

F: Fn(),

{

let start = std::time::Instant::now();

f();

start.elapsed().as_secs_f64()

}

// Function to plot attention heatmap

fn plot_attention(attn_weights: &Tensor, file_name: &str) {

let root_area = BitMapBackend::new(file_name, (1024, 1024)).into_drawing_area();

root_area.fill(&WHITE).unwrap();

let mut chart = ChartBuilder::on(&root_area)

.caption("Attention Heatmap", ("sans-serif", 50))

.margin(10)

.x_label_area_size(50)

.y_label_area_size(50)

.build_cartesian_2d(0..attn_weights.size()[1] as i32, 0..attn_weights.size()[2] as i32)

.unwrap();

chart.configure_mesh().draw().unwrap();

let attn_data: Vec<f32> = attn_weights.view([-1]).try_into().unwrap(); // Convert Tensor to Vec<f32>

let heatmap_data: Vec<_> = attn_data.chunks(attn_weights.size()[2] as usize).enumerate().collect();

for (i, row) in heatmap_data.iter() {

for (j, value) in row.iter().enumerate() {

let color_value = (*value * 255.0).clamp(0.0, 255.0) as u8;

chart.draw_series(PointSeries::of_element(

[((*i) as i32, j as i32)], // Ensure that both values are i32

3,

RGBColor(color_value, 0, 255 - color_value),

&|c, s, st| {

return EmptyElement::at(c)

+ Circle::new((0, 0), s, st.filled());

},

)).unwrap();

}

}

root_area.present().unwrap();

}

fn main() {

// Set up model variables and parameters

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(Device::cuda_if_available());

let embed_dim = 512;

let n_heads = 8;

let seq_length = 128;

let local_window_size = 32;

let dropout = 0.1;

// Create input tensors

let input = Tensor::randn(&[2, seq_length, embed_dim], (Kind::Float, Device::cuda_if_available()));

// Create Sparse Multi-Head Attention model

let sparse_attention = SparseMultiHeadAttention::new(&vs.root(), embed_dim, n_heads, local_window_size, dropout);

// Measure time for Sparse Multi-Head Attention and get attention weights

let sparse_time = measure_computation_time(|| {

let (_output, attn_probs) = sparse_attention.forward(&input, &input, &input);

plot_attention(&attn_probs, "attention_heatmap.png");

});

println!("Sparse Multi-Head Attention computation time: {:.6} seconds", sparse_time);

}

The SparseMultiHeadAttention struct defines a sparse attention mechanism by projecting query, key, and value tensors through learned linear transformations and applying scaled dot-product attention over a local window. The forward method computes the attention weights by multiplying query slices with corresponding key slices within a local range. These weights are then normalized using softmax and used to compute the final output by multiplying them with value tensors. The code also visualizes the computed attention weights using plotters, which generates a heatmap displaying the attention patterns across the sequence. The attention values are converted to a 2D array and plotted as colored circles where intensity reflects attention magnitude.

In conclusion, multi-head attention is a fundamental innovation in the Transformer model, allowing it to capture diverse relationships in sequences and improve performance across a range of NLP tasks. By enabling parallel attention computations across multiple heads, the Transformer can process sequences more efficiently and generalize better to complex language patterns. Implementing multi-head attention in Rust using tch-rs provides a practical way to explore its functionality and optimize the model for specific NLP applications.

4.4. Positional Encoding

One of the core innovations of the Transformer architecture is its ability to process input sequences in parallel, unlike traditional models like Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) that process sequences token by token. This parallelism significantly improves computational efficiency but introduces a fundamental challenge: since the Transformer does not process tokens in sequence, it lacks the inherent ability to understand the relative positions of words. To address this, the Transformer model incorporates positional encoding, which encodes the position of each token within the sequence so that the model can maintain awareness of word order.

Without positional information, the Transformer would be unable to distinguish between different arrangements of the same words, which is crucial for tasks like translation, text generation, and question answering. For instance, the sentences "The dog chased the cat" and "The cat chased the dog" contain the same words, but their meanings are entirely different due to word order. Positional encoding solves this problem by injecting information about each token's position in the sequence directly into the input embeddings before they are passed into the model.

The mathematical formulation of positional encoding used in the original Transformer model is based on sinusoidal functions, designed to provide a continuous and unique encoding for each position in the sequence. For a sequence of length $n$ with embedding dimension $d_{\text{model}}$, the positional encoding for each token position $pos$ is defined as:

$$ PE_{(pos, 2i)} = \sin\left(\frac{pos}{10000^{2i/d_{\text{model}}}}\right) $$

$$ PE_{(pos, 2i+1)} = \cos\left(\frac{pos}{10000^{2i/d_{\text{model}}}}\right) $$

Here, $pos$ represents the position of the token in the sequence, and $i$ represents the dimension within the embedding. This sinusoidal encoding ensures that each position has a unique representation, and it introduces a periodic structure that allows the model to generalize to unseen sequence lengths during inference. The sinusoidal nature of the encoding also ensures that nearby positions have similar encodings, which helps the model learn local dependencies between tokens. These positional encodings are added to the token embeddings before they are passed through the attention layers of the Transformer.

One of the key benefits of this approach is that it is deterministic and does not require additional parameters to learn the positional encodings. This makes it lightweight and scalable, as the same encoding can be applied across various tasks without the need for task-specific tuning. Moreover, the use of sine and cosine functions allows the encoding to capture patterns that vary over different frequencies, making it possible for the model to attend to both short- and long-range dependencies in the input.

Alternative methods of positional encoding have been explored as well. While the original Transformer used sinusoidal functions, some recent models have employed learned positional encodings, where the position information is represented as a learned vector that is trained alongside the rest of the model. This approach gives the model more flexibility in learning how to represent positions but comes at the cost of increased model complexity and potentially overfitting to the training data.

Another alternative approach is relative positional encoding, where instead of encoding the absolute position of each token, the model encodes the relative distance between tokens. This method can be particularly useful in tasks where the relationship between tokens is more important than their absolute positions, such as dependency parsing or long-range sequence modeling. Relative positional encodings have shown improved performance in some tasks, especially when the sequence length varies significantly between training and inference.

The choice of positional encoding can have a significant impact on model performance, particularly in tasks like translation or text generation, where the model needs to understand both local word order and broader syntactic structure. For example, in machine translation, accurately modeling the position of words is crucial for generating grammatically correct translations that preserve the meaning of the source sentence. Similarly, in text generation, positional encoding helps ensure that the generated sequence maintains coherence and follows the expected structure of the language.

However, positional encoding is not without limitations. The fixed nature of sinusoidal encodings can restrict the model’s ability to adapt to tasks where the importance of word order varies depending on context. Additionally, sinusoidal encoding may not be as effective in very long sequences, where the periodicity of the sine and cosine functions could cause ambiguity in distinguishing distant positions. These limitations have motivated ongoing research into more sophisticated and flexible methods of encoding position in sequences, such as learned and relative positional encodings.

In terms of practical implementation, sinusoidal positional encoding can be easily integrated into a Transformer model. Using Rust and the tch-rs crate, we can implement the sinusoidal positional encoding as follows:

use tch;

use tch::{Tensor, Kind};

fn positional_encoding(seq_len: i64, d_model: i64) -> Tensor {

let pe = Tensor::zeros(&[seq_len, d_model], (Kind::Float, tch::Device::Cpu));

for pos in 0..seq_len {

for i in (0..d_model).step_by(2) {

let angle = (pos as f64) / 10000f64.powf(2f64 * (i as f64) / d_model as f64);

let _ = pe.get(pos).get(i).fill_(angle.sin());

let _ = pe.get(pos).get(i + 1).fill_(angle.cos());

}

}

pe

}

fn main() {

let seq_len = 50;

let d_model = 512;

// Generate positional encodings for a sequence

let pe = positional_encoding(seq_len, d_model);

println!("Positional Encoding: {:?}", pe);

}

This code implements a function to generate positional encodings, commonly used in Transformer models to provide information about the position of tokens in a sequence. The function positional_encoding creates a tensor of shape [seq_len, d_model], where seq_len is the length of the input sequence and d_model is the model's dimensionality. The encoding is computed using sine and cosine functions at different frequencies for even and odd indices, respectively, based on the token's position and its index in the model's dimension. This encoding allows the model to leverage the relative positions of tokens since Transformers, unlike recurrent networks, do not inherently understand sequence order. In the main function, the positional encodings are computed for a sequence of length 50 and a model dimension of 512, and the result is printed.

Visualizing positional encodings can provide valuable insights into how the encodings represent word positions in a sequence. By plotting the positional encodings for a given sequence, we can observe how the sine and cosine functions encode the position in a smooth, continuous manner, and how the encoding changes across different dimensions. Visualization can also help us understand the periodic nature of the encoding and how it generalizes to unseen sequence lengths.

In addition to the sinusoidal method, experimenting with alternative positional encoding strategies in Rust can provide insights into their effectiveness in different tasks. For example, replacing the sinusoidal encoding with learned positional embeddings or relative encodings and comparing their impact on translation or text generation performance can help developers choose the optimal encoding strategy for their specific use case. Recent research has shown that learned encodings can sometimes outperform sinusoidal encodings in certain tasks, particularly when the model needs to learn task-specific representations of position.

The latest trends in positional encoding focus on making the Transformer more flexible and scalable. For instance, adaptive positional encodings dynamically adjust the encoding based on the length of the sequence, allowing the model to handle both short and long sequences more effectively. Additionally, rotary positional encoding has been proposed to improve the representation of angular relationships between tokens, making it more suitable for tasks that involve hierarchical structures.

In conclusion, positional encoding is a fundamental component of the Transformer model, enabling it to process sequences in parallel while maintaining an understanding of word order. The sinusoidal encoding method provides a simple and effective way to encode position without additional learned parameters, while alternative methods like learned and relative positional encodings offer more flexibility for specific tasks. By implementing and experimenting with different positional encoding strategies in Rust, developers can optimize the Transformer model for various NLP applications and ensure that it captures both local and global dependencies in the input data.

4.5. Encoder-Decoder Architecture

The encoder-decoder architecture is central to the design of the Transformer model, particularly in tasks that require generating a sequence of outputs based on an input sequence, such as machine translation or summarization. This architecture allows the model to first process the entire input sequence through the encoder, which generates context-aware representations of the input, and then utilize these representations in the decoder, where the output sequence is generated token by token. By separating the roles of encoding and decoding, the Transformer efficiently handles complex tasks requiring a deep understanding of input context and sequence generation.

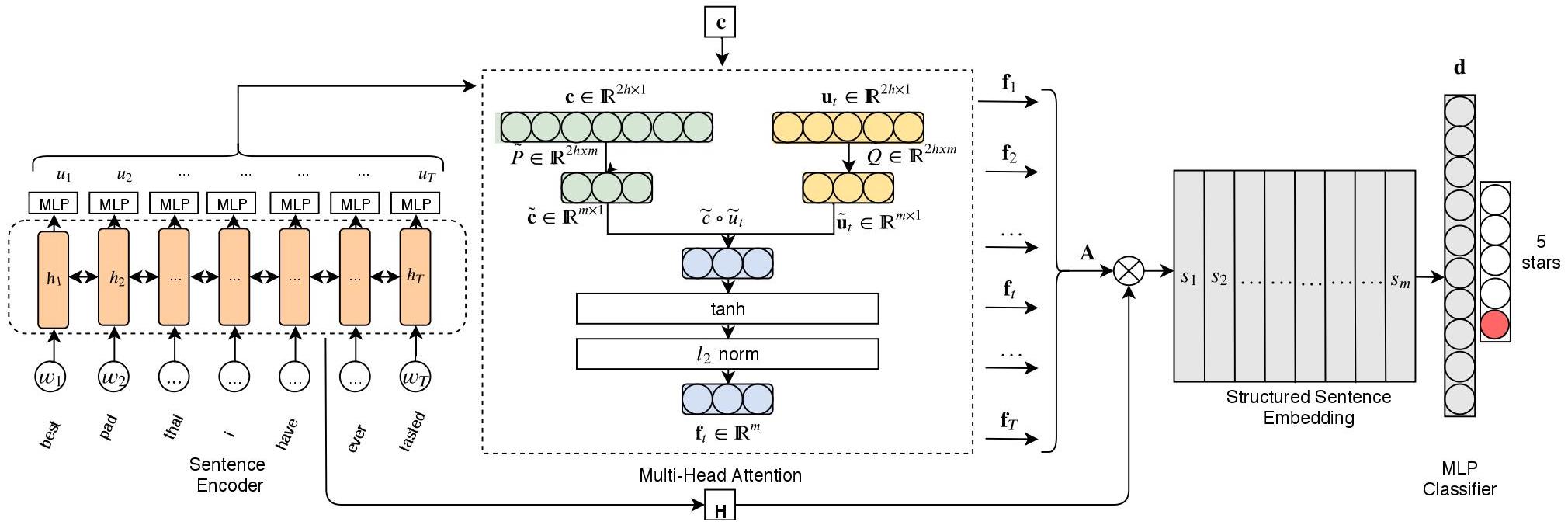

Figure 7: Encoder and decoder transformer architecture (Attention is all you need paper).

The encoder processes the input sequence $X = [x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n]$ and transforms each token into a contextualized representation. This is achieved by stacking multiple layers of self-attention and feedforward networks, where each layer refines the token representations based on both the local and global relationships within the sequence. Formally, given an input embedding $X$, the encoder generates a contextualized output $Z$, where:

$$ Z = \text{Encoder}(X) $$

Each token $z_i$ in the output $Z$ is not just a representation of the individual token $x_i$ but is enriched by information from the entire sequence, making it a powerful encoding that can be used for downstream tasks. This encoding process is crucial in tasks like translation, where each word in the source language must be interpreted in the context of the entire sentence before being translated.

The decoder, on the other hand, takes these contextualized representations $Z$ from the encoder and generates an output sequence $Y = [y_1, y_2, \dots, y_m]$, typically one token at a time. The decoder uses self-attention to model dependencies between previously generated tokens in the output sequence and cross-attention to attend to the encoder’s output. The cross-attention mechanism allows the decoder to focus on specific parts of the input sequence when generating each token. Formally, the decoder output $y_t$ at time step $t$ is computed as: