Chapter 3

Neural Networks Architectures for NLP

"The success of modern AI relies not just on algorithms, but on the architectures that support them, enabling us to build systems that can understand and generate human language with remarkable accuracy." — Yann LeCun

Chapter 3 of LMVR delves into the various neural network architectures that form the backbone of natural language processing (NLP). It begins with the fundamentals of neural networks, explaining the limitations of feedforward networks for NLP tasks and the necessity for more advanced architectures like Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs). The chapter then explores attention mechanisms and Transformers, highlighting their ability to handle long-range dependencies and scale effectively. Advanced models like BERT and GPT are discussed, emphasizing their pre-training and fine-tuning processes, and the chapter concludes with hybrid models and multi-task learning, showcasing how combining different architectures can enhance performance. Practical insights throughout the chapter guide readers in implementing these models using Rust, ensuring they can apply these techniques in real-world NLP tasks.

3.1. Introduction to Neural Networks for NLP

Neural networks have become a fundamental tool for processing and understanding natural language in modern artificial intelligence. At their core, neural networks are built from neurons (also known as units), which are mathematical functions designed to simulate the behavior of biological neurons. Each neuron receives inputs (represented as numerical vectors), applies a weighted transformation, and passes the result through an activation function to determine the output. These neurons are arranged into layers—typically including an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer—forming what is known as a feedforward neural network (FNN) or Multi Layer Perceptron (MLP) for some historical reason. While FNNs are powerful and have been successfully applied to various machine learning tasks, they face limitations when applied to natural language processing (NLP), primarily because language inherently involves context and sequence, which FNNs are not designed to handle efficiently.

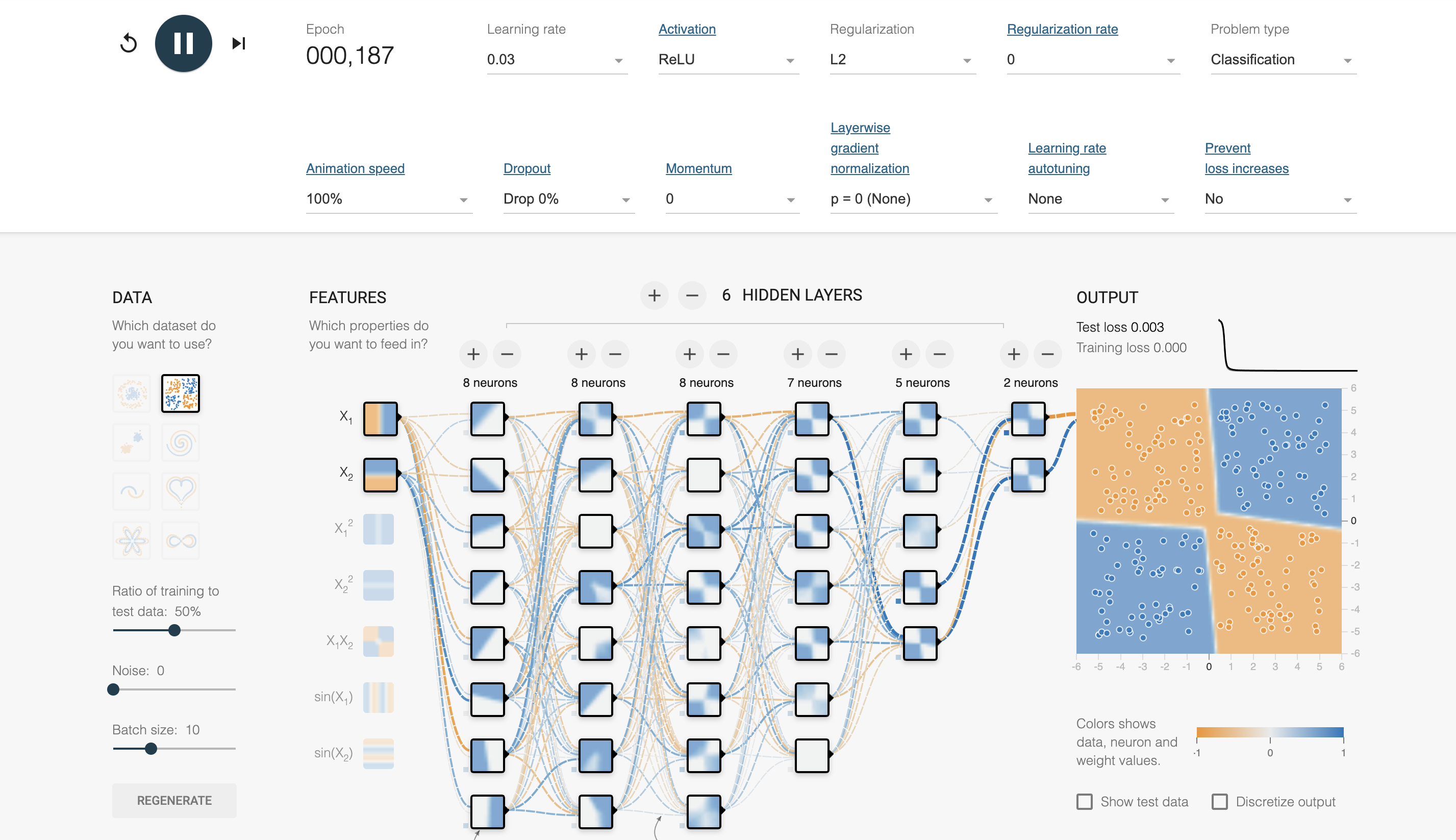

Figure 1: Interactive Learning tool for FNN or MLP architecture (https://deeperplayground.org).

A FNN or MLP is a type of artificial neural network where connections between the nodes do not form a cycle. It consists of multiple layers: an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer. Each layer is composed of neurons, and each neuron is connected to every neuron in the subsequent layer, allowing for complex transformations of the input data. These models are fundamental in many machine learning tasks, including classification, regression, and pattern recognition.

To explore this architecture using the deeperplayground tool, we begin by generating synthetic 2D data, typically a mixture of simple patterns such as clusters or spirals. The dataset is split into training and testing sets with a predefined ratio, for example, 70% training and 30% testing. The batch size, which controls the number of samples processed before the model updates its parameters, is typically chosen based on the complexity of the data and computational resources.

In this setting, the features of the dataset are two-dimensional, denoted as $x_1$ and $x_2$, representing the coordinates of each point in the 2D space. The goal of the MLP is to learn a decision boundary that separates or classifies the points based on these features. The interaction between $x_1$ and $x_2$ can be linear or involve more complex non-linear relationships, which the network learns during training. Combinations of $x_1$ and $x_2$, such as $x_1^2$, $x_1 x_2$, or $x_2^2$, may be implicitly captured by the model as it learns non-linear transformations through its hidden layers.

The MLP architecture in this scenario consists of two output neurons, corresponding to the two classes of the synthetic data (for binary classification). The hidden layer architecture comprises six hidden layers, each with a maximum of eight neurons. Mathematically, the transformation at each layer $l$ can be represented as:

$$ z^{(l)} = W^{(l)} a^{(l-1)} + b^{(l)} $$

$$ a^{(l)} = \sigma(z^{(l)}) $$

Here, $W^{(l)}$ represents the weight matrix of layer $l$, $b^{(l)}$ is the bias vector, $a^{(l-1)}$ is the activation from the previous layer, and $\sigma$ is the activation function applied element-wise (such as ReLU, sigmoid, or tanh). The output layer uses a softmax function for classification, defined as:

$$ \hat{y}_i = \frac{e^{z_i}}{\sum_j e^{z_j}} $$

This ensures that the output probabilities sum to one. The MLP learns by minimizing the cross-entropy loss:

$$ L(y, \hat{y}) = - \sum_i y_i \log(\hat{y}_i) $$

where $y$ is the true label, and $\hat{y}$ is the predicted output.

During the training of a neural network, the process of updating the weights is guided by an optimization algorithm, such as gradient descent, aimed at minimizing the loss function. The loss function, denoted by $L(y, \hat{y})$, quantifies the difference between the true output $y$ and the predicted output $\hat{y}$. The goal is to adjust the model’s parameters (weights and biases) in such a way that the loss function is minimized, thus improving the model's predictive accuracy.

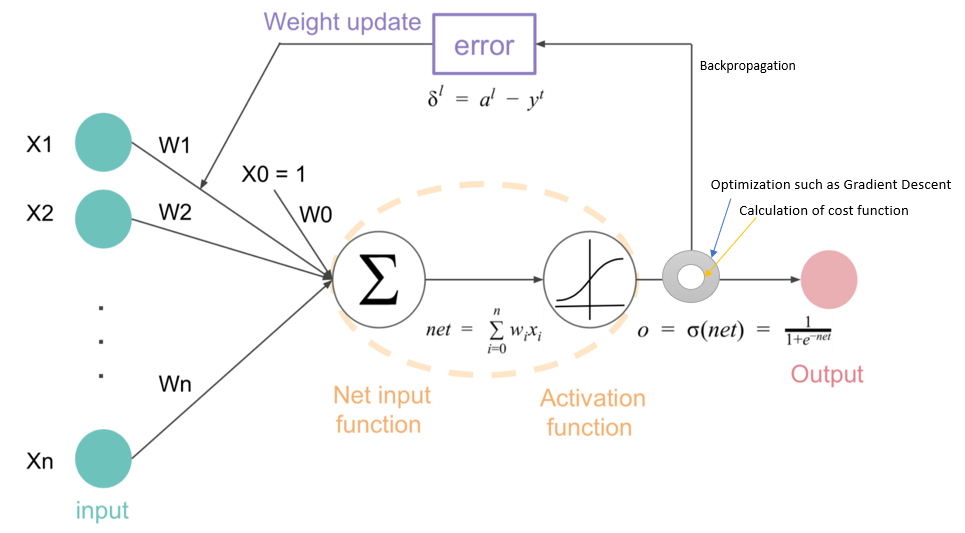

Figure 2: Backpropagation and gradient descent.

To minimize the loss, the gradient descent algorithm computes the gradient of the loss function with respect to each weight $W^{(l)}$ and bias $b^{(l)}$ in the network. This gradient tells us the direction in which the weights should be adjusted to reduce the loss. The weight update rule for a weight $W_{ij}^{(l)}$ in layer $l$, connecting neuron $i$ in layer $l-1$ to neuron $j$ in layer $l$, is defined as:

$$ W_{ij}^{(l)} \leftarrow W_{ij}^{(l)} - \eta \frac{\partial L}{\partial W_{ij}^{(l)}} $$

Here, $\eta$ is the learning rate, a hyperparameter that controls the step size of the update. The term $\frac{\partial L}{\partial W_{ij}^{(l)}}$ is the partial derivative of the loss function with respect to the weight $W_{ij}^{(l)}$, which tells us how much the loss changes with a small change in $W_{ij}^{(l)}$. This derivative is calculated using the backpropagation algorithm, a recursive application of the chain rule of calculus.

For the biases, the update rule is similar:

$$ b_j^{(l)} \leftarrow b_j^{(l)} - \eta \frac{\partial L}{\partial b_j^{(l)}} $$

The backpropagation algorithm works by computing the gradient of the loss function with respect to each weight and bias in the network by propagating the error backwards through the network. For each layer, starting from the output layer, we compute the error at each neuron and propagate this error back to the previous layer. The error signal at layer $l$, denoted by $\delta^{(l)}$, is the gradient of the loss with respect to the weighted input of that layer $z^{(l)}$:

$$ \delta_j^{(l)} = \frac{\partial L}{\partial z_j^{(l)}} $$

This error signal is used to compute the gradients with respect to the weights and biases. For the weights, the gradient is given by:

$$ \frac{\partial L}{\partial W_{ij}^{(l)}} = \delta_j^{(l)} a_i^{(l-1)} $$

where $a_i^{(l-1)}$ is the activation of the iii-th neuron in the previous layer. For the biases, the gradient is simply:

$$ \frac{\partial L}{\partial b_j^{(l)}} = \delta_j^{(l)} $$

The error signal $\delta^{(l)}$ is recursively computed starting from the output layer. For the output layer, it is the derivative of the loss with respect to the weighted input:

$$ \delta_j^{(L)} = \frac{\partial L}{\partial z_j^{(L)}} = \hat{y}_j - y_j $$

For hidden layers, the error is propagated backwards using the derivative of the activation function $\sigma$ and the error from the next layer:

$$ \delta_j^{(l)} = \left( \sum_k W_{jk}^{(l+1)} \delta_k^{(l+1)} \right) \sigma'(z_j^{(l)}) $$

Here, $\sigma'(z_j^{(l)})$ is the derivative of the activation function (e.g., ReLU, sigmoid) applied to the weighted input at neuron $j$ in layer $l$.

Momentum is an extension of gradient descent that helps to accelerate convergence and smooth out the optimization process, especially in the presence of oscillations. It works by adding a fraction of the previous update to the current update, allowing the algorithm to accumulate velocity in directions of consistent gradients. The update rule with momentum is:

$$ v_{ij}^{(l)} \leftarrow \gamma v_{ij}^{(l)} + \eta \frac{\partial L}{\partial W_{ij}^{(l)}} $$

$$ W_{ij}^{(l)} \leftarrow W_{ij}^{(l)} - v_{ij}^{(l)} $$

Here, $v_{ij}^{(l)}$ represents the velocity or momentum term, and $\gamma$ (typically between 0 and 1) is the momentum coefficient. The momentum term accelerates the updates in the relevant direction and dampens oscillations, making it particularly useful in deep networks where gradients may vary significantly across layers.

The learning rate $\eta$ determines the step size for each update. A small learning rate leads to more gradual, but stable, updates, while a large learning rate may cause the optimization to overshoot the minimum of the loss function, potentially causing divergence.

Training is typically done over multiple epochs, where each epoch represents one complete pass through the entire training dataset. The number of epochs is a hyperparameter that affects how long the model trains. Too few epochs may result in underfitting (the model hasn’t learned enough), while too many may lead to overfitting (the model learns noise in the data).

In conclusion, the process of minimizing the loss function in neural networks involves computing gradients via backpropagation, updating the weights and biases through gradient descent, and optionally using momentum to accelerate learning. The learning rate and number of epochs are crucial hyperparameters that govern the speed and convergence of the model's training.

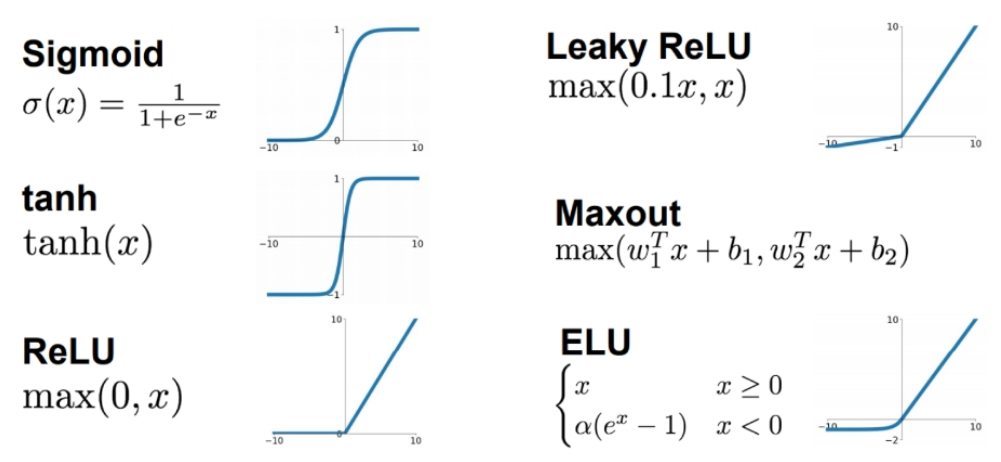

The activation function used in the hidden layers significantly affects the model's ability to capture non-linearities. ReLU is commonly used for hidden layers because it introduces non-linearity while avoiding vanishing gradients. Dropout is applied to prevent overfitting by randomly "dropping" a proportion of neurons during each update, ensuring that the model does not rely too heavily on any particular neuron.

Figure 3: MLP activation functions.

To prevent overfitting and improve generalization, regularization techniques such as $L_2$-regularization (weight decay) are applied, adding a penalty term to the loss function:

$$ L_{\text{reg}} = L(y, \hat{y}) + \lambda \sum_i ||W_i||_2^2 $$

where $\lambda$ is the regularization strength.

Layerwise gradient normalization helps ensure stable learning by normalizing the gradients across different layers, preventing them from becoming too large or too small. This is particularly important in deep networks to prevent gradient vanishing or explosion. Additionally, the learning rate can be auto-tuned during training by using techniques like adaptive learning rates (e.g., AdaGrad or Adam), which dynamically adjust the learning rate based on the gradient's magnitude. Furthermore, mechanisms can be put in place to prevent loss increases, such as early stopping, where training halts if the loss on the validation set begins to rise, or by using gradient clipping to limit the gradient's magnitude, avoiding instability.

In the Deeperplayground tool, the training process can be visualized through real-time plots of the training and testing loss, helping to monitor the model's progress and detect potential overfitting if the training loss decreases while the testing loss rises. The decision boundary evolves as the model learns, and the interplay between the hyperparameters (e.g., learning rate, momentum, regularization) and the model's capacity (number of neurons, layers) becomes apparent as the loss is optimized.

This mathematical framework and visualization through Deeperplayground provides an intuitive yet rigorous understanding of how MLPs work, how they can be tuned, and the impact of their architecture and hyperparameters on the model’s performance.

In NLP, language is sequential and highly dependent on context. A word's meaning often changes based on the surrounding words, known as the contextual dependence of language. Traditional FNNs or MLPs, however, treat input data as independent and static, making it difficult for them to capture the dependencies between words in a sequence. While FNNs can model simple relationships between words or tokens, they struggle with understanding longer dependencies and nuances in language. This limitation becomes more apparent when dealing with more complex NLP tasks such as text classification, sentiment analysis, or machine translation, where understanding the meaning of the entire sentence (or longer sequences) is crucial.

Mathematically, the output of a neuron in a feedforward neural network is given by:

$$ y = \sigma\left( \sum_{i=1}^{n} w_i x_i + b \right) $$

where $x_i$ are the input values, $w_i$ are the weights, $b$ is the bias term, and $\sigma$ is the activation function (such as ReLU or sigmoid). The sum represents the weighted input, and the activation function introduces non-linearity into the network, allowing it to model more complex patterns. However, in NLP, where sequential data is prevalent, this structure does not account for the order of the words or their dependencies. Hence, FNNs tend to struggle in capturing the semantic meaning of text as they do not process sequences in a temporal manner, making it hard to generate meaningful results for language-based tasks.

Deep networks, as opposed to shallow networks with only one or two hidden layers, are better equipped to handle more complex NLP tasks. Deep neural networks consist of multiple layers that allow them to extract hierarchical features from the input data. In NLP, deeper layers can capture higher-level abstractions, moving from basic token-level features in the early layers to sentence-level or paragraph-level semantics in the later layers. However, even deep feedforward networks have their limitations in sequence modeling because they lack mechanisms to account for temporal dependencies or long-range context, which are crucial for understanding language meaningfully.

The challenge of applying traditional neural networks to sequence data in NLP is mainly due to their inability to process data sequentially. For example, in a sentence like "The dog chased the cat," a neural network must understand that "the dog" is the subject and "the cat" is the object, and these relationships depend on the order of the words. Feedforward networks do not retain this information because they treat inputs independently. Moreover, long-range dependencies, such as when a word refers to something mentioned earlier in the text (e.g., "the cat" in a later sentence referring to the cat mentioned previously), cannot be effectively captured by these networks. These shortcomings highlight the need for more advanced architectures like recurrent neural networks (RNNs) or transformer models that are designed to handle sequence data and maintain context across time steps.

To provide a practical illustration, a simple FNN can be implemented in Rust for basic NLP tasks like sentiment analysis or text classification. Using Rust’s tch-rs crate, which provides bindings to the Torch deep learning library, we can construct, train, and evaluate a feedforward neural network.

The provided code demonstrates how to implement FNN or MLP in Rust using the tch-rs crate, a Rust binding for the PyTorch deep learning library. The MLP is designed for a multi-class classification task and utilizes synthetic data to simulate input and output features. This setup showcases how to build and train neural networks in Rust, specifically leveraging ReLU activations, dropout for regularization, and the Adam optimizer for efficient gradient-based learning. The architecture is flexible and scalable, making it suitable for tasks like text classification or other NLP applications.

[dependencies]

tch = "0.12.0"

use tch::{nn, nn::Module, nn::OptimizerConfig, Device, Tensor, Kind};

// Function to generate synthetic dataset

fn generate_synthetic_data(num_samples: usize, input_size: usize, num_classes: usize) -> (Tensor, Tensor) {

let inputs = Tensor::randn(&[num_samples as i64, input_size as i64], (Kind::Float, Device::Cpu));

let targets = Tensor::randint(num_classes as i64, &[num_samples as i64], (Kind::Int64, Device::Cpu));

(inputs, targets)

}

// Define the neural network architecture

fn build_mlp(vs: &nn::Path, input_size: i64, hidden_layers: &[i64], output_size: i64) -> nn::Sequential {

let mut net = nn::seq();

// Input to first hidden layer

net = net.add(nn::linear(vs, input_size, hidden_layers[0], Default::default()));

net = net.add_fn(|xs| xs.relu());

// Adding intermediate hidden layers with dropout

for i in 0..hidden_layers.len() - 1 {

net = net.add(nn::linear(vs, hidden_layers[i], hidden_layers[i + 1], Default::default()));

net = net.add_fn(|xs| xs.relu());

net = net.add_fn(|xs| xs.dropout(0.3, true)); // Dropout for regularization, `add_fn` instead of `add_fn_t`

}

// Last hidden layer to output

net = net.add(nn::linear(vs, hidden_layers[hidden_layers.len() - 1], output_size, Default::default()));

net

}

fn main() {

// Set the device to CUDA if available

let device = Device::cuda_if_available();

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(device);

// Define MLP architecture: Input -> Hidden Layers -> Output

let input_size = 100;

let hidden_layers = vec![128, 64, 32]; // 3 hidden layers of decreasing size

let output_size = 5; // Multi-class classification with 5 classes

let net = build_mlp(&vs.root(), input_size, &hidden_layers, output_size);

// Generate synthetic data (1000 samples, 100 features, 5 classes)

let (train_input, train_target) = generate_synthetic_data(1000, input_size as usize, output_size as usize);

let (test_input, test_target) = generate_synthetic_data(200, input_size as usize, output_size as usize);

// Define optimizer (Adam with learning rate 0.001)

let mut opt = nn::Adam::default().build(&vs, 1e-3).unwrap();

let epochs = 1000;

let batch_size = 32;

// Training loop

for epoch in 1..=epochs {

let num_batches = (train_input.size()[0] as f64 / batch_size as f64).ceil() as i64;

for batch_idx in 0..num_batches {

// Generate batch

let batch_start = batch_idx * batch_size;

let batch_end = (batch_start + batch_size).min(train_input.size()[0]);

let input_batch = train_input.narrow(0, batch_start, batch_end - batch_start).to(device);

let target_batch = train_target.narrow(0, batch_start, batch_end - batch_start).to(device);

// Forward pass

let output = net.forward(&input_batch);

// Compute the loss (cross-entropy for multi-class classification)

let loss = output.cross_entropy_for_logits(&target_batch);

// Backpropagation and optimization

opt.backward_step(&loss);

}

// Evaluate on training and testing datasets

let train_loss = net.forward(&train_input.to(device)).cross_entropy_for_logits(&train_target.to(device));

let test_loss = net.forward(&test_input.to(device)).cross_entropy_for_logits(&test_target.to(device));

// Use `double_value(&[])` to extract scalar from Tensor

println!(

"Epoch: {}, Train Loss: {:.4}, Test Loss: {:.4}",

epoch,

train_loss.double_value(&[]),

test_loss.double_value(&[])

);

}

}

This Rust code utilizes the tch-rs library (a Rust wrapper for PyTorch) to define, train, and evaluate a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) for multi-class classification. It generates synthetic datasets with a specified number of samples, features, and classes, then builds an MLP architecture with an input layer, multiple hidden layers with ReLU activations and dropout regularization, and an output layer. The network is trained using stochastic gradient descent with the Adam optimizer, and cross-entropy loss is used for backpropagation. The training loop runs for a specified number of epochs, processes batches of input data, and computes losses for both the training and testing datasets. The loss values are then extracted and displayed for each epoch, giving insight into the model's performance over time.

In industry, feedforward neural networks were initially applied to NLP tasks such as document classification and bag-of-words models. These models work well for tasks where word order is not critical and where there are clear separations between categories. However, their limitations in handling sequences and long-range dependencies became apparent as more complex NLP tasks emerged. This prompted the development and adoption of more advanced architectures, such as Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), Long Short-Term Memory networks (LSTMs), and eventually the Transformer model, which powers state-of-the-art models like GPT-3 and BERT.

The latest trends in NLP architecture design emphasize the need for models that capture both short- and long-range dependencies in text. This shift led to the development of attention-based models and Transformers, which process input data in parallel and handle sequence dependencies more effectively. While feedforward networks can still be useful for simpler tasks or as building blocks in larger systems, they are often insufficient for state-of-the-art language modeling. Transformer models, with their ability to capture complex dependencies and parallelize computations, have become the new standard for handling language data at scale.

In conclusion, while feedforward neural networks represent an essential starting point for understanding the mechanics of neural networks in NLP, they have significant limitations in processing the sequential and contextual nature of language. Rust’s performance capabilities, combined with powerful libraries like tch-rs, allow for efficient implementation and experimentation with these basic models. However, as NLP tasks grow in complexity, more advanced architectures like RNNs and Transformers are necessary to capture the full richness of language and achieve state-of-the-art performance.

3.2. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs)

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) have been a cornerstone of neural network architectures for modeling sequential data, making them particularly well-suited for Natural Language Processing (NLP) tasks. Unlike feedforward neural networks, which treat each input independently, RNNs introduce recurrent connections, enabling them to maintain an internal state that evolves as they process input sequences. This internal state allows RNNs to capture temporal dependencies in data, making them highly effective for tasks where context and sequence matter, such as language modeling, text generation, and machine translation.

Figure 4: An RNN with hidden state (Credit to d2l.ai)

Mathematically, RNNs operate by applying the same function at each time step of the input sequence. Given an input sequence $x_1, x_2, \dots, x_T$, the RNN updates its hidden state $H_t$ at each time step using the following recurrence relation:

$$ h_t = \phi(W_{hh} H_{t-1} + W_{xh} x_t + b_h) $$

where $W_{hh}$ represents the recurrent weight matrix (mapping the previous hidden state to the current hidden state), $W_{xh}$ is the input weight matrix (mapping the current input to the hidden state), and $\phi$ is the activation function of fully connected (FC) layer, typically the tanh or ReLU function. The final output at each time step can be computed as:

$$y_t = W_{hy} H_t + b_y$$

where $W_{hy}$ is the output weight matrix, and $b_y$ is the output bias. The key strength of RNNs lies in their ability to retain information across time steps, enabling them to process variable-length sequences while maintaining memory of past inputs.

In Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), the ability to model sequence data comes from the recurrent connections that allow information to persist across time steps. However, this same recurrent structure introduces significant challenges during the training process, particularly the vanishing and exploding gradient problems. These issues arise during the training phase when using a process known as Backpropagation Through Time (BPTT), which extends the standard backpropagation algorithm to sequences by unrolling the network over multiple time steps. In BPTT, gradients are propagated backward in time from the final time step to the initial time step to compute the necessary weight updates.

Mathematically, we can represent an RNN's output at time ttt as a function of its previous hidden state $H_{t-1}$, the input at time $t$ is $x_t$, and its current weights $W$. This is typically written as:

$$ H_t = \phi(W_h H_{t-1} + W_x x_t + b) $$

where $W_h$ is the weight matrix for the hidden state, $W_x$ is the weight matrix for the input, $b$ is the bias, and $\sigma$ is a non-linear activation function like tanh or ReLU. The goal of training is to minimize a loss function $L$, which is computed by comparing the network's output at each time step to the actual target values. The BPTT algorithm calculates the gradients of this loss function with respect to the network's weights by recursively applying the chain rule.

The key issue in BPTT arises from the recursive nature of gradient computation. Specifically, at each time step, the gradient of the loss with respect to the weight matrix $W_h$ involves multiplying a series of Jacobians (derivatives of hidden states with respect to previous hidden states). For long sequences, this leads to an expression like:

$$ \frac{\partial L}{\partial W_h} = \sum_{t=1}^{T} \left( \frac{\partial L}{\partial H_t} \prod_{k=t}^{T} \frac{\partial H_{k}}{\partial H_{k-1}} \right) $$

Each term in this product represents the derivative of the hidden state at time $k$ with respect to the hidden state at time $k-1$. As the number of time steps $T$ increases, the product of these Jacobians can either shrink exponentially (leading to vanishing gradients) or grow exponentially (leading to exploding gradients) depending on the eigenvalues of $W_h$.

In the case of vanishing gradients, the Jacobians contain values less than one (due to non-linear activations like tanh or sigmoid), causing the gradient to shrink rapidly as it is propagated back through time. Formally, if $|\lambda_{\text{max}}(W_h)| < 1∣$, where $\lambda_{\text{max}}(W_h)$ represents the largest eigenvalue of the matrix $W_h$, the gradients will decay exponentially. As a result, gradients associated with earlier time steps become negligibly small, and the model fails to learn long-term dependencies because updates to the weights are minimal.

Conversely, exploding gradients occur when $\lambda_{\text{max}}(W_h)| > 1$, leading to an exponential growth in the gradients as they are propagated backward. In this scenario, the gradients become extremely large, causing unstable training. This results in excessively large weight updates during backpropagation, which may lead the optimization process to diverge, making it impossible for the model to converge on a solution.

To combat these problems, several techniques have been developed. For vanishing gradients, architectures like Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks and Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs) are designed to maintain gradients over long sequences by incorporating gating mechanisms that control the flow of information. For exploding gradients, gradient clipping is often employed, which scales down the gradients when their norms exceed a certain threshold, ensuring that they remain manageable during backpropagation.

Figure 5: A LSTM cell with hidden state (Credit d2l.ai).

LSTMs introduce a more sophisticated architecture to mitigate the vanishing gradient problem by incorporating gates that control the flow of information. Each LSTM unit has three gates: the forget gate, input gate, and output gate, which allow the model to retain or discard information over long sequences. The key equations governing LSTMs are:

$$ F_t = \sigma(W_f \cdot [H_{t-1}, x_t] + b_f) $$

$$ I_t = \sigma(W_i \cdot [H_{t-1}, x_t] + b_i) $$

$$ O_t = \sigma(W_o \cdot [H_{t-1}, x_t] + b_o) $$

$$ \tilde{C}_t = \tanh(W_C \cdot [H_{t-1}, x_t] + b_C) $$

$$ C_t = F_t \odot C_{t-1} + i_t \odot \tilde{C}_t $$

$$ H_t = o_t \odot \tanh(C_t) $$

Here, $F_t$, $I_t$, and $O_t$ represent the forget, input, and output gates, respectively. $C_t$ is the cell state, which acts as a memory that can retain information over long sequences. By regulating the flow of information through these gates, LSTMs can learn long-term dependencies more effectively than standard RNNs.

Figure 6: A GRU cell with hidden state.

GRUs simplify the LSTM architecture by using only two gates: the update gate and reset gate, reducing the complexity while still addressing the vanishing gradient problem. The update gate controls how much of the previous hidden state to carry forward, and the reset gate determines how much of the past information to discard. The equations governing GRUs are:

$$ Z_t = \sigma(W_z \cdot [H_{t-1}, x_t]) $$

$$ R_t = \sigma(W_r \cdot [H_{t-1}, x_t]) $$

$$ \tilde{H}_t = \tanh(W \cdot [r_t \odot H_{t-1}, x_t]) $$

$$ H_t = (1 - z_t) \odot H_{t-1} + Z_t \odot \tilde{H}_t $$

Here, $z_t$ is the update gate and $r_t$ is the reset gate. GRUs are often preferred over LSTMs when computational efficiency is a concern, as they have fewer parameters while still effectively handling long-term dependencies.

One of the key advantages of RNNs is their ability to capture temporal dependencies in text, which makes them well-suited for tasks like language modeling and text generation. Language modeling involves predicting the next word in a sequence based on the previous words, and RNNs can model this sequential dependence by maintaining a hidden state that evolves as new words are processed. For example, in a sentence like "The dog chased the cat," an RNN can remember that the subject of the sentence is "The dog" while processing the rest of the sentence, enabling it to generate grammatically correct and contextually relevant continuations.

However, while RNNs, LSTMs, and GRUs can capture long-range dependencies, they come with trade-offs between model complexity and performance. LSTMs, with their more complex gating mechanisms, tend to perform better on tasks requiring long-term memory, but they are computationally more expensive than simple RNNs. GRUs, by reducing the number of gates, strike a balance between performance and efficiency. In practice, the choice between these variants depends on the specific NLP task, the length of the sequences involved, and the computational resources available.

For practical task, we will build a simple character-level language model using Rust and the tch-rs crate, which provides bindings to PyTorch, allowing us to construct, train, and evaluate LSTM and GRU usefficiently. The provided code implements a character-level language model using two different types of recurrent neural networks (RNNs): Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Gated Recurrent Units (GRU). The model is trained on a dataset of text (Shakespeare's works) to predict the next character in a sequence, with the goal of generating text that resembles the style of the input data. The code allows for comparison between the performance of LSTM and GRU models during training, tracking their losses and generating sample text to demonstrate how well the models can learn patterns in the data.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0.90"

tch = "0.12.0"

tokio = "1.40.0"

reqwest = { version = "0.11", features = ["blocking"] }

plotters = "0.3.7"

use anyhow::Result;

use std::fs;

use std::path::Path;

use std::io::Write;

use reqwest;

use tch::data::TextData;

use tch::nn::{Linear, Module, OptimizerConfig, LSTM, GRU};

use tch::{nn, Device, Kind, Tensor};

use tch::nn::RNN; // Import RNN trait for LSTM and GRU

use plotters::prelude::*; // Import plotters for visualization

const LEARNING_RATE: f64 = 0.01;

const HIDDEN_SIZE: i64 = 256;

const SEQ_LEN: i64 = 180;

const BATCH_SIZE: i64 = 256;

const EPOCHS: i64 = 100;

const SAMPLING_LEN: i64 = 1024;

const INPUT_URL: &str = "https://raw.githubusercontent.com/karpathy/char-rnn/master/data/tinyshakespeare/input.txt";

const INPUT_FILE: &str = "data/input.txt";

/// Downloads a file from the specified URL and saves it to a local file.

fn download_input_file() -> Result<()> {

let response = reqwest::blocking::get(INPUT_URL)?;

let content = response.text()?;

// Create the local directory if it doesn't exist

let path = Path::new("data");

if !path.exists() {

fs::create_dir_all(path)?;

}

// Save the content to the input file

let mut file = fs::File::create(INPUT_FILE)?;

file.write_all(content.as_bytes())?;

println!("Downloaded and saved input file to: {}", INPUT_FILE);

Ok(())

}

/// Generates some sample string using LSTM.

fn sample_lstm(data: &TextData, lstm: &LSTM, linear: &Linear, device: Device) -> String {

let labels = data.labels();

let mut state = lstm.zero_state(1); // Initialize LSTM hidden state

let mut last_label = 0i64;

let mut result = String::new();

for _index in 0..SAMPLING_LEN {

let input = Tensor::zeros([1, labels], (Kind::Float, device));

let _ = input.narrow(1, last_label, 1).fill_(1.0);

state = lstm.step(&input, &state); // Perform LSTM step

// Extract hidden state (h) from LSTMState

let h = &state.0 .0; // Access the LSTM hidden state `h` from LSTMState

let sampled_y = linear

.forward(h) // Pass only `h` (the hidden state tensor) to the forward function

.squeeze_dim(0)

.softmax(-1, Kind::Float)

.multinomial(1, false);

last_label = i64::try_from(sampled_y).unwrap();

result.push(data.label_to_char(last_label))

}

result

}

/// Generates some sample string using GRU.

fn sample_gru(data: &TextData, gru: &GRU, linear: &Linear, device: Device) -> String {

let labels = data.labels();

let mut state = gru.zero_state(1); // Initialize GRU hidden state

let mut last_label = 0i64;

let mut result = String::new();

for _index in 0..SAMPLING_LEN {

let input = Tensor::zeros([1, labels], (Kind::Float, device));

let _ = input.narrow(1, last_label, 1).fill_(1.0);

state = gru.step(&input, &state); // Perform GRU step and reassign the state

// GRU returns only h as GRUState

let h = &state.0; // Access the GRU hidden state `h` from GRUState

let sampled_y = linear

.forward(h) // Pass the hidden state tensor `h` to the forward function

.squeeze_dim(0)

.softmax(-1, Kind::Float)

.multinomial(1, false);

last_label = i64::try_from(sampled_y).unwrap();

result.push(data.label_to_char(last_label))

}

result

}

pub fn plot_losses(lstm_losses: &[f64], gru_losses: &[f64]) -> Result<()> {

let root = BitMapBackend::new("loss_comparison.png", (640, 480)).into_drawing_area();

root.fill(&WHITE)?;

let mut chart = ChartBuilder::on(&root)

.caption("LSTM vs GRU Loss Comparison", ("sans-serif", 20))

.margin(10)

.x_label_area_size(30)

.y_label_area_size(30)

.build_cartesian_2d(0..EPOCHS, 0.0..lstm_losses.iter().cloned().fold(0.0/0.0, f64::max))?;

chart.configure_mesh().draw()?;

chart

.draw_series(LineSeries::new(

(0..).zip(lstm_losses.iter().cloned()),

&BLUE,

))?

.label("LSTM")

.legend(|(x, y)| PathElement::new(vec![(x, y), (x + 20, y)], &BLUE));

chart

.draw_series(LineSeries::new(

(0..).zip(gru_losses.iter().cloned()),

&RED,

))?

.label("GRU")

.legend(|(x, y)| PathElement::new(vec![(x, y), (x + 20, y)], &RED));

chart.configure_series_labels().border_style(&BLACK).draw()?;

Ok(())

}

pub fn main() -> Result<()> {

// Download the input file if it doesn't already exist

if !Path::new(INPUT_FILE).exists() {

download_input_file()?;

}

let device = Device::cuda_if_available();

let vs_lstm = nn::VarStore::new(device);

let vs_gru = nn::VarStore::new(device);

let data = TextData::new(INPUT_FILE)?;

let labels = data.labels();

println!("Dataset loaded, {labels} labels.");

// Define LSTM and GRU models

let lstm = nn::lstm(vs_lstm.root(), labels, HIDDEN_SIZE, Default::default());

let gru = nn::gru(vs_gru.root(), labels, HIDDEN_SIZE, Default::default());

let linear_lstm = nn::linear(vs_lstm.root(), HIDDEN_SIZE, labels, Default::default());

let linear_gru = nn::linear(vs_gru.root(), HIDDEN_SIZE, labels, Default::default());

let mut opt_lstm = nn::Adam::default().build(&vs_lstm, LEARNING_RATE)?;

let mut opt_gru = nn::Adam::default().build(&vs_gru, LEARNING_RATE)?;

let mut lstm_losses = vec![];

let mut gru_losses = vec![];

// Training loop for both LSTM and GRU

for epoch in 1..(1 + EPOCHS) {

let mut sum_loss_lstm = 0.;

let mut sum_loss_gru = 0.;

let mut cnt_loss = 0.;

for batch in data.iter_shuffle(SEQ_LEN + 1, BATCH_SIZE) {

let xs_onehot = batch.narrow(1, 0, SEQ_LEN).onehot(labels);

let ys = batch.narrow(1, 1, SEQ_LEN).to_kind(Kind::Int64);

// LSTM training step

let (lstm_out, _) = lstm.seq(&xs_onehot.to_device(device)); // Use `seq` for LSTM

let logits_lstm = linear_lstm.forward(&lstm_out);

let loss_lstm = logits_lstm

.view([BATCH_SIZE * SEQ_LEN, labels])

.cross_entropy_for_logits(&ys.to_device(device).view([BATCH_SIZE * SEQ_LEN]));

opt_lstm.backward_step_clip(&loss_lstm, 0.5);

// GRU training step

let (gru_out, _) = gru.seq(&xs_onehot.to_device(device)); // Use `seq` for GRU

let logits_gru = linear_gru.forward(&gru_out);

let loss_gru = logits_gru

.view([BATCH_SIZE * SEQ_LEN, labels])

.cross_entropy_for_logits(&ys.to_device(device).view([BATCH_SIZE * SEQ_LEN]));

opt_gru.backward_step_clip(&loss_gru, 0.5);

sum_loss_lstm += f64::try_from(loss_lstm)?;

sum_loss_gru += f64::try_from(loss_gru)?;

cnt_loss += 1.0;

}

let avg_loss_lstm = sum_loss_lstm / cnt_loss;

let avg_loss_gru = sum_loss_gru / cnt_loss;

lstm_losses.push(avg_loss_lstm);

gru_losses.push(avg_loss_gru);

println!("Epoch: {} LSTM loss: {:5.3} GRU loss: {:5.3}", epoch, avg_loss_lstm, avg_loss_gru);

println!("Sample (LSTM): {}", sample_lstm(&data, &lstm, &linear_lstm, device));

println!("Sample (GRU): {}", sample_gru(&data, &gru, &linear_gru, device));

}

// Plot the loss comparison

plot_losses(&lstm_losses, &gru_losses)?;

Ok(())

}

The code begins by downloading the input text data and preparing it for training. Both LSTM and GRU models are defined using the tch crate, with their respective hidden states and parameters initialized. The training loop shuffles the data, processes it in batches, and feeds it into both models. For each epoch, the code computes the loss for both LSTM and GRU models using cross-entropy loss, optimizes the models using the Adam optimizer, and logs the loss for comparison. After each epoch, it generates sample text from both models to evaluate their text generation abilities. At the end of training, the losses for LSTM and GRU are plotted using the plotters crate to visualize the performance of both models across epochs.

Despite the advances in RNNs and their variants, addressing the vanishing gradient problem remains a critical concern, particularly when dealing with long sequences. One approach to mitigating this issue is through gradient clipping, which restricts the magnitude of the gradients during backpropagation to prevent them from becoming too large and destabilizing the training process. In Rust, this can be implemented by modifying the gradient values before updating the model’s parameters. Other techniques, such as initializing weights properly or using regularization (e.g., dropout), can also help improve the stability and performance of RNNs during training.

In recent years, the Transformer architecture has largely supplanted RNNs in many NLP tasks due to its ability to process sequences in parallel and handle long-range dependencies more effectively. However, RNNs, LSTMs, and GRUs still have valuable applications, particularly in scenarios where sequence length is moderate, and computational efficiency is a priority. For example, speech recognition, time series forecasting, and certain sequence labeling tasks continue to benefit from these recurrent architectures.

In conclusion, Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), along with their variants like LSTMs and GRUs, provide powerful tools for handling sequential data in NLP. Their ability to capture temporal dependencies in text makes them highly suitable for tasks such as language modeling and text generation. Implementing these models in Rust using the tch-rs crate allows for efficient, high-performance training on large-scale datasets, while addressing challenges such as the vanishing gradient problem through advanced implementation techniques. Despite the rise of newer architectures like Transformers, RNNs continue to play a vital role in specific NLP applications.

3.3. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for NLP

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), originally developed for image processing, have been successfully adapted for various NLP tasks. At their core, CNNs use convolutional layers to apply filters (or kernels) that slide over the input data to detect patterns or features. In the context of NLP, these filters help capture local patterns in text, such as n-grams or short phrases, which can be useful for tasks like text classification and sentiment analysis. CNNs are especially effective in recognizing important subsequences in text data, as they focus on small regions of input at a time.

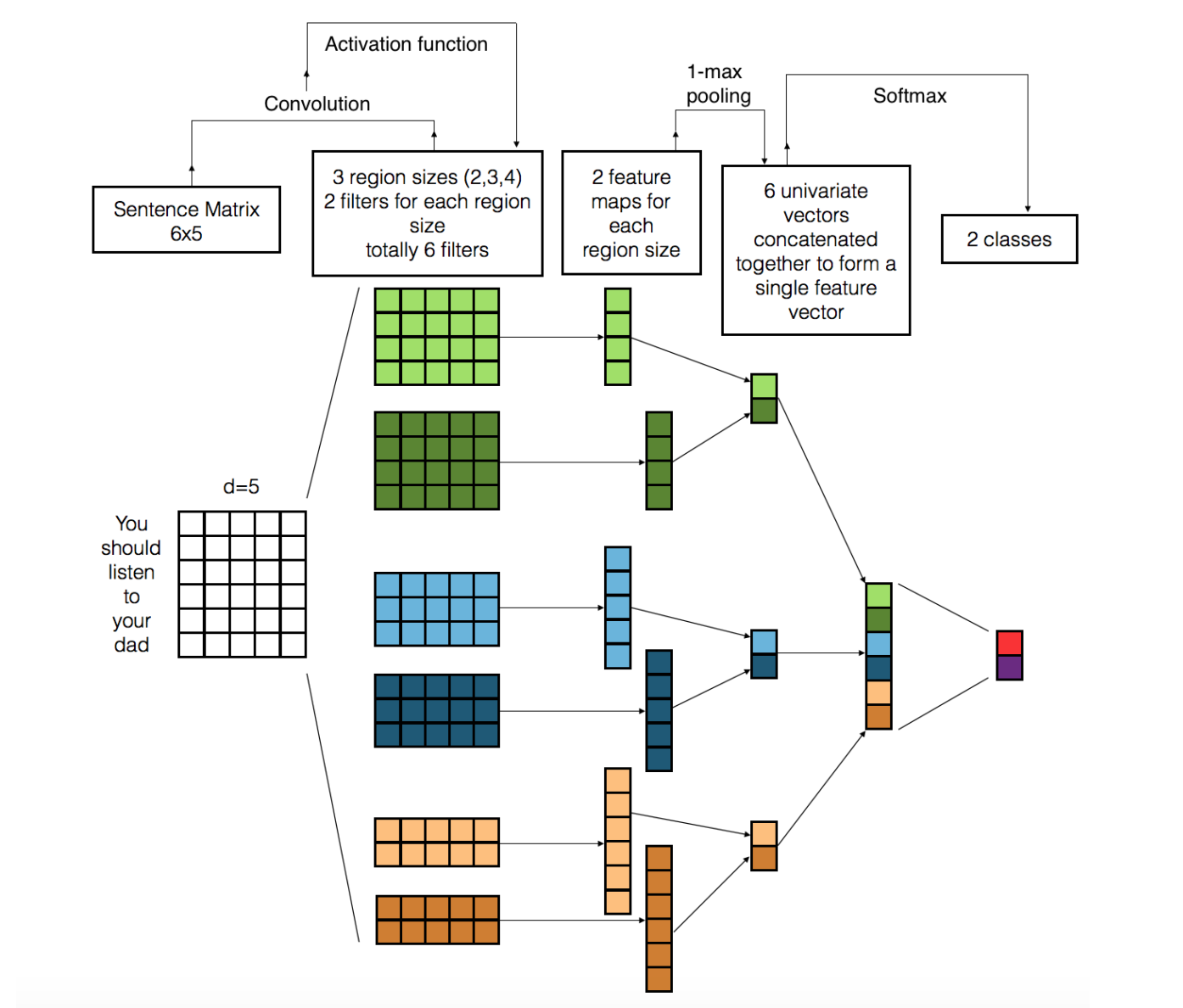

Figure 7: Illustration of CNN architecture for NLP task (Ref: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1703.03091).

Mathematically, a convolutional operation in a CNN involves applying a kernel $K$ to an input $X$ to generate a feature map $Y$. For a 1D CNN (which is used in NLP tasks), the convolution is expressed as:

$$ Y(i) = \sum_{j} K(j) \cdot X(i + j) $$

Here, $K(j)$ is the kernel applied over the input sequence $X$, and the result is a feature map $Y$ that highlights the important local features in the input. The kernel effectively "scans" through the input, identifying patterns such as word combinations or local structures in the text.

Unlike the 2D convolutions used in image processing (where kernels move over 2D image grids), 1D convolutions in NLP operate over sequences of words or tokens, focusing on extracting local dependencies in a one-dimensional vector space. In image processing, the kernels capture spatial features, such as edges or textures, whereas in NLP, the 1D kernels capture local syntactic and semantic patterns in text. For example, a 1D kernel may detect meaningful bi-grams or tri-grams in a sentence, which can be indicative of sentiment or intent in text classification.

One of the main advantages of CNNs in NLP is their ability to capture local patterns with limited computational complexity. By applying multiple kernels of different sizes, CNNs can extract various n-gram features across different layers, allowing them to learn a rich set of representations. After the convolution operation, pooling layers (typically max pooling) are applied to reduce the dimensionality of the feature maps, retaining only the most important features. Pooling also helps make the model more robust to small shifts in the input, making CNNs suitable for processing noisy or unstructured text data.

While CNNs are effective at capturing local dependencies, they have limitations when it comes to long-range dependencies in text. For instance, in tasks like machine translation or long document classification, understanding the broader context is crucial. CNNs, by design, are constrained by the size of the kernels, making them less effective at modeling relationships between distant words. For these tasks, Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Transformer models tend to perform better, as they are better equipped to handle sequence-wide information and long-range dependencies.

However, CNNs can still be highly effective when combined with other architectures. For example, in hybrid models, CNNs are used to capture local features, while RNNs or Transformers handle the global context. These hybrid architectures take advantage of the CNN’s ability to efficiently extract local patterns and combine it with the sequential capabilities of RNNs or the parallel processing power of Transformers. This fusion is particularly useful in tasks like document classification, named entity recognition, or text summarization, where both local and global features need to be modeled.

A significant application of CNNs in NLP is text classification, where the goal is to categorize a given text into predefined classes, such as sentiment analysis (positive/negative), spam detection, or topic categorization. CNNs have been shown to work effectively for this task because they can quickly identify key phrases or patterns that are indicative of a class. For example, in sentiment analysis, CNNs can identify phrases like "very good" or "extremely bad" by applying filters that capture local features, which can then be pooled and used for classification.

In terms of practical implementation, constructing CNNs in Rust is possible using libraries like burn or tch-rs, which offer high-level abstractions for building and training neural networks. The provided Rust code is designed to download the CIFAR-10 dataset, train a Fast ResNet model on it, and visualize the loss versus epochs during the training process. It leverages various libraries such as tch (which provides bindings for PyTorch), plotters (for plotting loss graphs), and reqwest (for downloading the dataset). The model training workflow involves data augmentation, forward propagation through the ResNet architecture, loss calculation using cross-entropy, and updating model weights through stochastic gradient descent (SGD) with momentum. Additionally, it tracks the average loss for each epoch and generates a plot for the loss trend over time.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0.90"

tch = "0.12.0"

tokio = "1.40.0"

reqwest = { version = "0.11", features = ["blocking"] }

plotters = "0.3.7"

flate2 = "1.0.34"

tar = "0.4.42"

use anyhow::Result;

use plotters::prelude::*;

use std::fs::{self, File};

use std::io::Write;

use tch::nn::{FuncT, ModuleT, OptimizerConfig, SequentialT};

use tch::{nn, Device};

use std::path::Path;

use flate2::read::GzDecoder;

use tar::Archive;

use reqwest::blocking::Client;

use reqwest::header::USER_AGENT;

use std::thread;

use std::time::Duration;

fn download_with_retries(url: &str, retries: u32, wait: u64) -> Result<Vec<u8>> {

let client = Client::builder()

.timeout(Duration::from_secs(300)) // 5 minute timeout

.build()?;

for attempt in 0..retries {

match client.get(url)

.header(USER_AGENT, "Rust CIFAR Downloader")

.send() {

Ok(response) => {

let bytes = response.bytes()?;

return Ok(bytes.to_vec());

}

Err(err) => {

println!("Attempt {} failed: {}. Retrying in {} seconds...", attempt + 1, err, wait);

thread::sleep(Duration::from_secs(wait)); // Wait before retrying

}

}

}

Err(anyhow::anyhow!("Failed to download dataset after {} attempts", retries))

}

fn download_cifar() -> Result<()> {

let base_url = "https://www.cs.toronto.edu/~kriz/cifar-10-binary.tar.gz";

let data_dir = "data";

let archive_path = format!("{}/cifar-10-binary.tar.gz", data_dir);

if !Path::new(data_dir).exists() {

fs::create_dir(data_dir)?;

}

if !Path::new(&archive_path).exists() {

println!("Downloading CIFAR-10 dataset...");

// Retry downloading the dataset 3 times with a 10-second wait between attempts

let response = download_with_retries(base_url, 3, 10)?;

let mut file = File::create(&archive_path)?;

file.write_all(&response)?;

println!("Download complete.");

}

// Untar the dataset

let tar_gz = File::open(&archive_path)?;

let tar = GzDecoder::new(tar_gz);

let mut archive = Archive::new(tar);

archive.unpack(data_dir)?;

Ok(())

}

fn conv_bn(vs: &nn::Path, c_in: i64, c_out: i64) -> SequentialT {

let conv2d_cfg = nn::ConvConfig { padding: 1, bias: false, ..Default::default() };

nn::seq_t()

.add(nn::conv2d(vs, c_in, c_out, 3, conv2d_cfg))

.add(nn::batch_norm2d(vs, c_out, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

}

fn layer<'a>(vs: &nn::Path, c_in: i64, c_out: i64) -> FuncT<'a> {

let pre = conv_bn(&vs.sub("pre"), c_in, c_out);

let block1 = conv_bn(&vs.sub("b1"), c_out, c_out);

let block2 = conv_bn(&vs.sub("b2"), c_out, c_out);

nn::func_t(move |xs, train| {

let pre = xs.apply_t(&pre, train).max_pool2d_default(2);

let ys = pre.apply_t(&block1, train).apply_t(&block2, train);

pre + ys

})

}

fn fast_resnet(vs: &nn::Path) -> SequentialT {

nn::seq_t()

.add(conv_bn(&vs.sub("pre"), 3, 64))

.add(layer(&vs.sub("layer1"), 64, 128))

.add(conv_bn(&vs.sub("inter"), 128, 256))

.add_fn(|x| x.max_pool2d_default(2))

.add(layer(&vs.sub("layer2"), 256, 512))

.add_fn(|x| x.max_pool2d_default(4).flat_view())

.add(nn::linear(vs.sub("linear"), 512, 10, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x * 0.125)

}

fn learning_rate(epoch: i64) -> f64 {

if epoch < 50 {

0.1

} else if epoch < 100 {

0.01

} else {

0.001

}

}

fn plot_loss(losses: Vec<f64>) -> Result<()> {

let root = BitMapBackend::new("loss_vs_epoch.png", (1024, 768))

.into_drawing_area();

root.fill(&WHITE)?;

let max_loss = losses.iter().cloned().fold(f64::NAN, f64::max);

let mut chart = ChartBuilder::on(&root)

.caption("Loss vs Epoch", ("sans-serif", 40).into_font())

.margin(10)

.x_label_area_size(40)

.y_label_area_size(40)

.build_cartesian_2d(0..losses.len(), 0.0..max_loss)?;

chart.configure_mesh().draw()?;

chart

.draw_series(LineSeries::new(

losses.iter().enumerate().map(|(x, y)| (x, *y)),

&RED,

))?

.label("Training Loss")

.legend(|(x, y)| PathElement::new([(x, y), (x + 20, y)], &RED));

chart.configure_series_labels().draw()?;

Ok(())

}

pub fn main() -> Result<()> {

// Step 1: Download the dataset if not already available

download_cifar()?;

// Step 2: Load the CIFAR dataset

let m = tch::vision::cifar::load_dir("data/cifar-10-batches-bin")?;

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(Device::cuda_if_available());

let net = fast_resnet(&vs.root());

// Step 3: Set up optimizer and loss tracking

let mut opt = nn::Sgd { momentum: 0.9, dampening: 0., wd: 5e-4, nesterov: true }

.build(&vs, 0.)?;

let mut losses = vec![]; // To store losses for plotting

// Step 4: Train the model

for epoch in 1..150 {

opt.set_lr(learning_rate(epoch));

let mut epoch_loss = 0.0;

let mut batch_count = 0;

for (bimages, blabels) in m.train_iter(64).shuffle().to_device(vs.device()) {

let bimages = tch::vision::dataset::augmentation(&bimages, true, 4, 8);

let loss = net.forward_t(&bimages, true).cross_entropy_for_logits(&blabels);

opt.backward_step(&loss);

epoch_loss += loss.double_value(&[]); // Extract scalar from tensor

batch_count += 1;

}

let avg_loss = epoch_loss / batch_count as f64;

losses.push(avg_loss); // Store average loss for the epoch

let test_accuracy =

net.batch_accuracy_for_logits(&m.test_images, &m.test_labels, vs.device(), 512);

println!(

"epoch: {:4} test acc: {:5.2}% avg loss: {:.4}",

epoch, 100. * test_accuracy, avg_loss

);

}

// Step 5: Plot the loss vs. epoch

plot_loss(losses)?;

Ok(())

}

The code begins by ensuring the CIFAR-10 dataset is downloaded using the reqwest library with a retry mechanism to handle possible network issues. Once downloaded and extracted, the CIFAR-10 dataset is loaded for training using the tch::vision utilities. The Fast ResNet model is built using a series of convolutional layers with batch normalization and ReLU activation functions. During training, the model undergoes forward passes on mini-batches of data, and the loss is computed and used to update the model's weights via backpropagation. The loss for each epoch is tracked and plotted using the plotters crate, giving a visual representation of the model's learning process over time. This allows for easier evaluation of the training performance and any potential overfitting or underfitting.

When working with CNNs in NLP, experimenting with different kernel sizes and architectures is crucial for optimizing performance. For instance, small kernel sizes (e.g., 2-3 words) capture fine-grained features such as bi-grams, while larger kernel sizes can capture broader phrases. Additionally, stacking multiple convolutional layers can allow the network to learn more abstract features as the input is passed through deeper layers.

Despite their effectiveness in certain tasks, CNNs alone may struggle with long-range dependencies, making them less suitable for tasks that require understanding entire documents or long sentences. In recent years, Transformers have become the dominant architecture for these tasks due to their ability to handle global context efficiently. However, CNNs still offer significant advantages in terms of computational efficiency and can be highly effective when used as part of hybrid models, combining their ability to capture local patterns with the global context provided by RNNs or Transformers.

The latest trends in CNNs for NLP focus on integrating convolutional layers with attention mechanisms and Transformers. For example, some hybrid models use CNNs to preprocess text and extract local features before passing the data to Transformer layers for more comprehensive processing. This combination allows for efficient feature extraction while maintaining the ability to capture long-range dependencies, resulting in more robust models for tasks like document summarization, question answering, and language translation.

In conclusion, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have proven to be a valuable tool in NLP, particularly for tasks that require capturing local patterns in text. While CNNs excel at processing local features and n-grams, they are less effective at handling long-range dependencies, which limits their application in more complex NLP tasks. By integrating CNNs with other architectures like RNNs and Transformers, we can build hybrid models that benefit from both local pattern recognition and long-range context processing. Rust, with libraries like burn and tch-rs, provides a powerful and efficient platform for implementing and optimizing CNNs for NLP, enabling developers to experiment with different architectures and improve model performance in real-world applications.

3.4. Attention Mechanisms and Transformers

The development of attention mechanisms has revolutionized the field of Natural Language Processing (NLP), enabling models to focus on specific parts of an input sequence that are most relevant to a given task. The core idea behind attention is to allow a model to assign different levels of importance (or weights) to different tokens (words or subwords) in a sequence, rather than processing all tokens uniformly. Self-attention, the foundation of the Transformer model, allows each token in a sequence to attend to every other token, capturing dependencies between words regardless of their distance in the sequence. This mechanism enables models to handle complex language structures with long-range dependencies more efficiently than previous architectures like Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) or Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs).

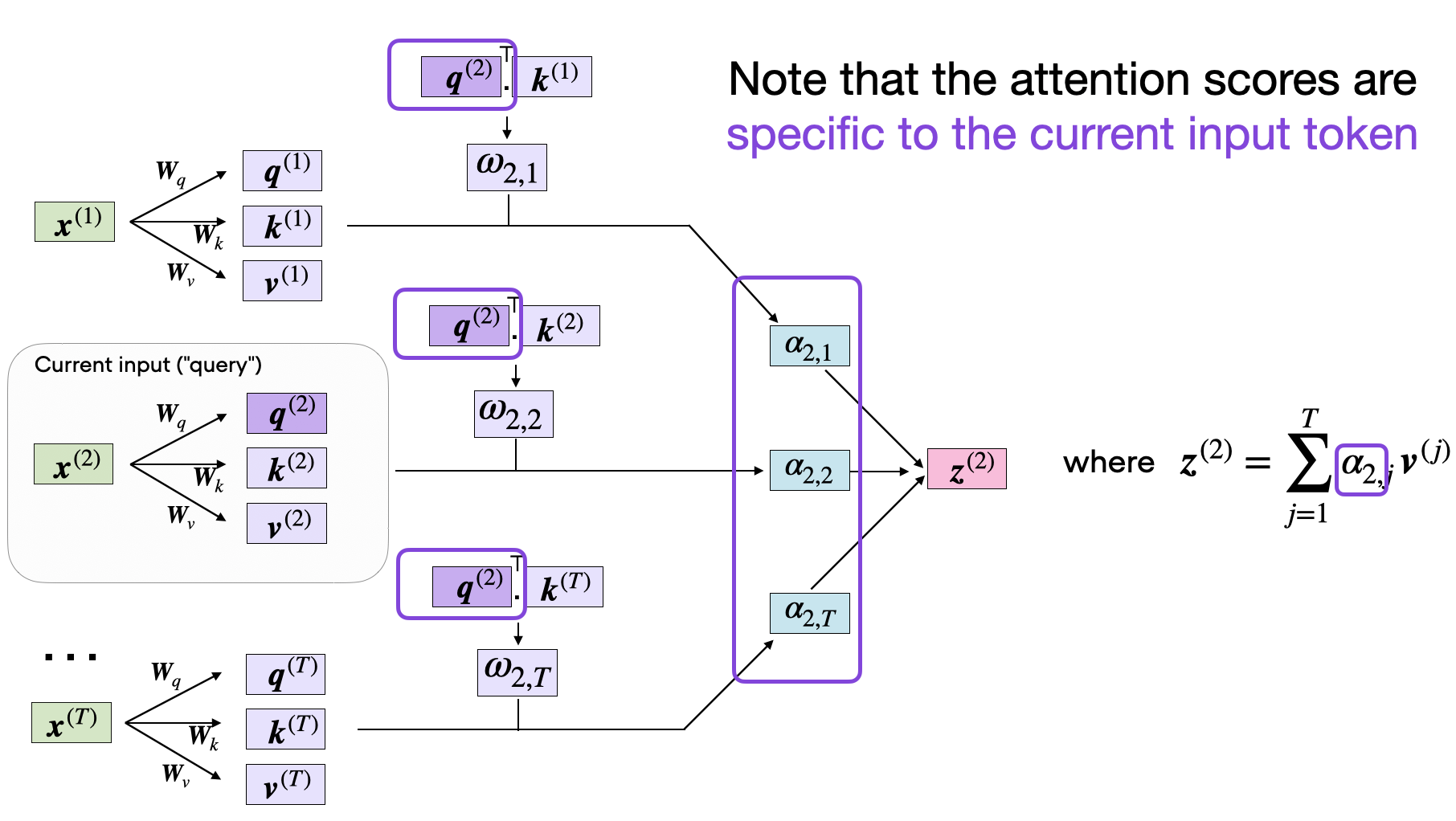

Figure 8: Understanding self-attention mechanism (Credit: Sebastian Raschka)

Mathematically, self-attention computes a weighted sum of input representations, where the weights represent the relevance between tokens in a sequence. Given an input sequence of tokens $X = [x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n]$, self-attention first transforms each token into three vectors: Query $Q$, Key $K$, and Value $V$. These vectors are learned during training, and the attention score between two tokens is computed by taking the dot product between the query vector of one token and the key vector of another, followed by a scaling and softmax operation to obtain normalized weights:

$$ \text{Attention}(Q, K, V) = \text{softmax}\left( \frac{QK^T}{\sqrt{d_k}} \right) V $$

Here, $d_k$ is the dimensionality of the key vectors, and the softmax function ensures that the weights are normalized to sum to 1. The result is a weighted sum of the value vectors, where tokens that are more relevant to each other (based on their query-key similarity) contribute more to the final output. Multi-head attention extends this idea by allowing the model to compute multiple sets of attention scores (or "heads") in parallel, capturing different aspects of the input relationships. The output of the multiple heads is concatenated and linearly transformed to produce the final attention output.

The Transformer architecture represents a revolutionary shift in neural network design, introduced in the groundbreaking 2017 paper "Attention is All You Need." It replaced the need for recurrence and convolution in modeling sequential data, enabling more efficient processing and representation of long-range dependencies. At its core, a Transformer model relies on self-attention mechanisms, allowing it to weigh the importance of different words in a sequence to one another, facilitating complex pattern recognition. This has made Transformers the foundation for advanced language models like GPT (OpenAI), Llama (Meta), and Gemini (Google). Their success in NLP tasks has spurred applications in other domains, such as image processing, protein folding, and even game playing.

The transformer architecture consists of two main components: the encoder and the decoder. Each encoder layer comprises two critical sublayers—a multi-head self-attention mechanism and a feedforward neural network. In contrast, the decoder adds an additional cross-attention mechanism to focus on relevant parts of the encoder’s output, making it particularly effective in sequence-to-sequence tasks such as machine translation.

Figure 9: Transformer architecture.

The key advantage of Transformers over RNNs and CNNs lies in their ability to process sequences in parallel rather than sequentially. In RNNs, each token must be processed in the order it appears in the sequence, which makes it challenging to capture long-range dependencies and results in slower training due to the lack of parallelization. CNNs, while more parallelizable, are limited by their kernel sizes, which makes it difficult for them to capture dependencies between distant words. In contrast, the self-attention mechanism in Transformers enables each token to attend to all other tokens in the sequence, regardless of their position, and the architecture can be parallelized efficiently. This makes Transformers highly scalable and computationally efficient for large datasets and long sequences, leading to breakthroughs in NLP tasks such as translation, summarization, and language modeling.

One of the most important aspects of attention is its ability to focus on relevant parts of the input. For example, in machine translation, a Transformer can attend to the most relevant words in the source sentence while generating the target sentence, ensuring that the translation is both accurate and contextually meaningful. This selective attention allows the model to learn which words are most important for predicting the next token in the sequence, rather than treating all input tokens equally.

Transformers are highly flexible and can be configured in different ways depending on the task. The most common Transformer models are categorized into three types:

Encoder-only models (e.g., BERT) focus on understanding input sequences and are often used for tasks like text classification and question answering. The encoder processes the entire input sequence simultaneously and outputs contextualized representations for each token.

Decoder-only models (e.g., GPT) are designed for tasks like text generation, where the goal is to predict the next word given a partial sequence. The decoder generates the output sequence one token at a time, with each new token attending to both the input context and previously generated tokens.

Encoder-decoder models (e.g., T5, BART) are used for tasks that require both understanding and generating text, such as machine translation and summarization. The encoder processes the input sequence, while the decoder generates the output sequence based on the encoder’s representations.

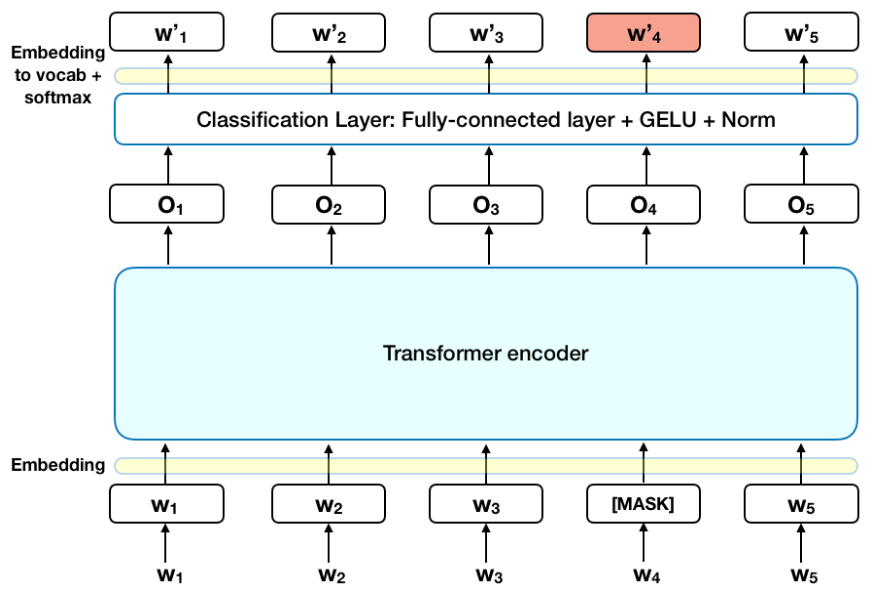

BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) is a groundbreaking Transformer model introduced by Google in 2018. It is built on the Transformer architecture and designed to understand the context of words in relation to one another in a sentence. Unlike previous models that processed text in a left-to-right or right-to-left manner, BERT is bidirectional, meaning it reads text both ways. This allows BERT to capture richer context and better understand the meaning of words based on the words that appear both before and after them.

Figure 10: BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) architecture.

In high-performing models like BERT, there are typically 12 layers, each with 12 distinct self-attention heads. These attention heads calculate attention weights that reflect how much each token in a sentence attends to every other token, forming attention maps. For BERT, this results in a massive number of attention weights—12 × 12 × number of tokens × number of tokens for each text instance. Notably, researchers have found that some attention heads correspond to meaningful linguistic properties, such as word semantics or syntactic dependencies.

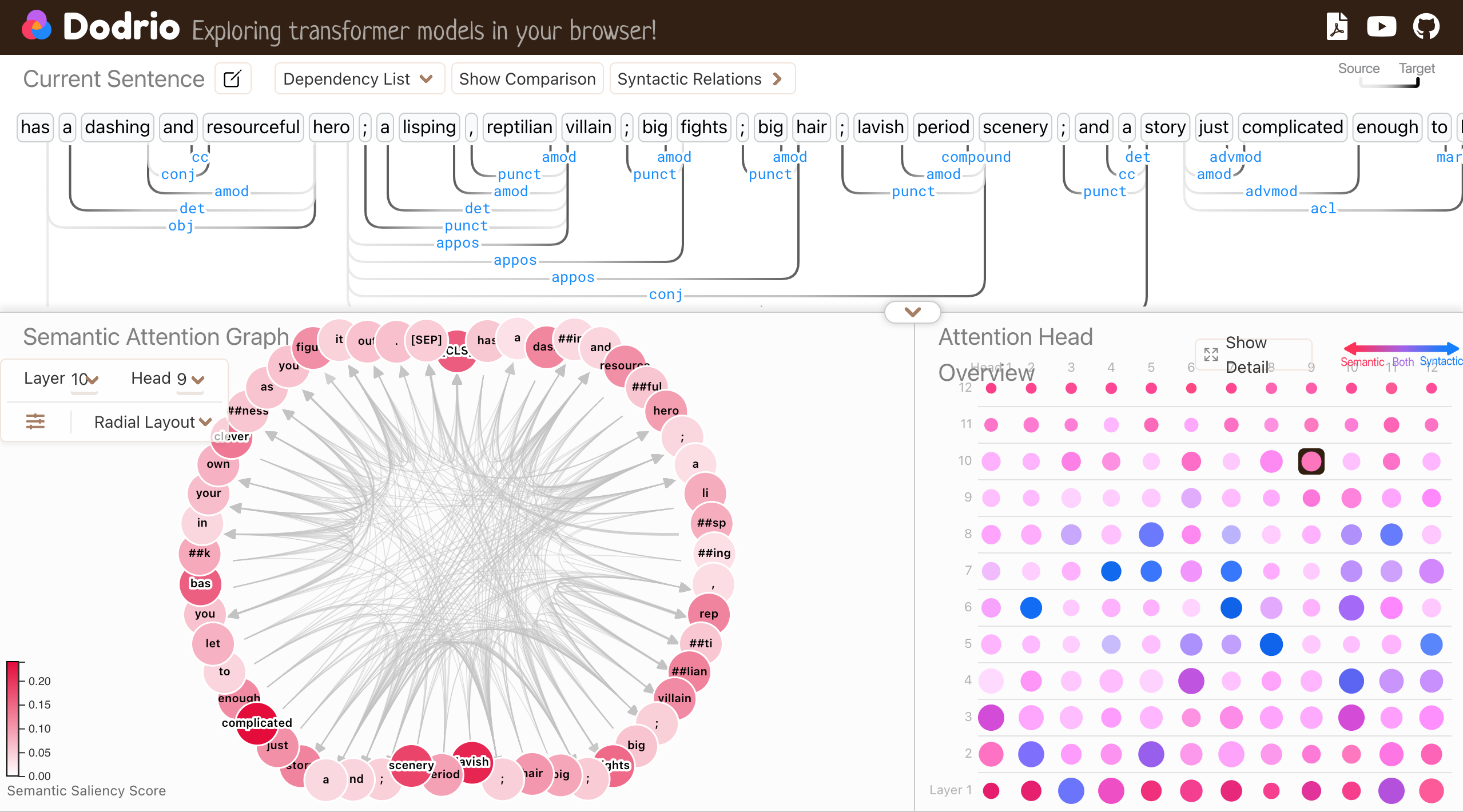

Figure 11: Dodrio interactive tool to understand how multi-head attentions work.

To make the exploration and interpretation of these attention weights easier, [Dodrio](https://poloclub.github.io/dodrio/), an interactive visualization tool, addresses these challenges by summarizing attention heads and providing both semantic and syntactic knowledge contexts. In Dodrio’s interface, you can explore the Attention Head Overview (bottom right) to identify which linguistic properties an attention head focuses on. By clicking on an attention head, you can explore the semantic and syntactic significance of a given sentence for that specific head. Dodrio’s Dependency View and Comparison View (top) allow you to examine how attention heads reflect lexical dependencies in a sentence, while the Semantic Attention Graph view (bottom left) provides insight into the semantic relationships that attention heads capture. For instance, attention heads can highlight coreferences (how different parts of a text refer to the same entity) or word sense disambiguation.

By using Dodrio’s interactive visualizations, you can dive into the multi-headed attention mechanism across different text instances, gaining deeper insights into how Transformers model the intricate linguistic relationships in natural language. Dodrio provides a valuable tool to explore the inner workings of large models like BERT, making attention weights more interpretable and aligned with linguistic features

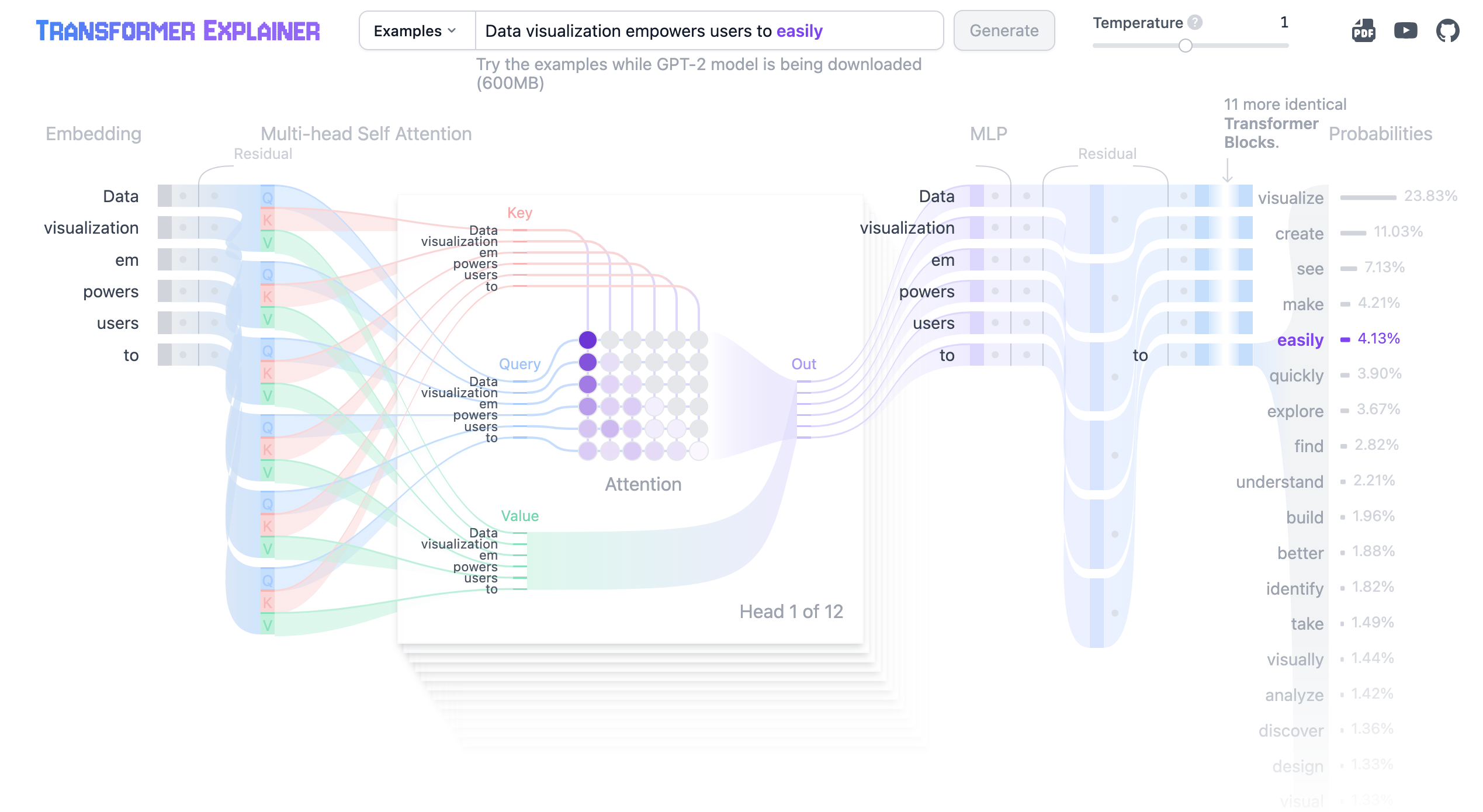

Figure 12: Transformer Explainer tool to understand how transformer works for language model.

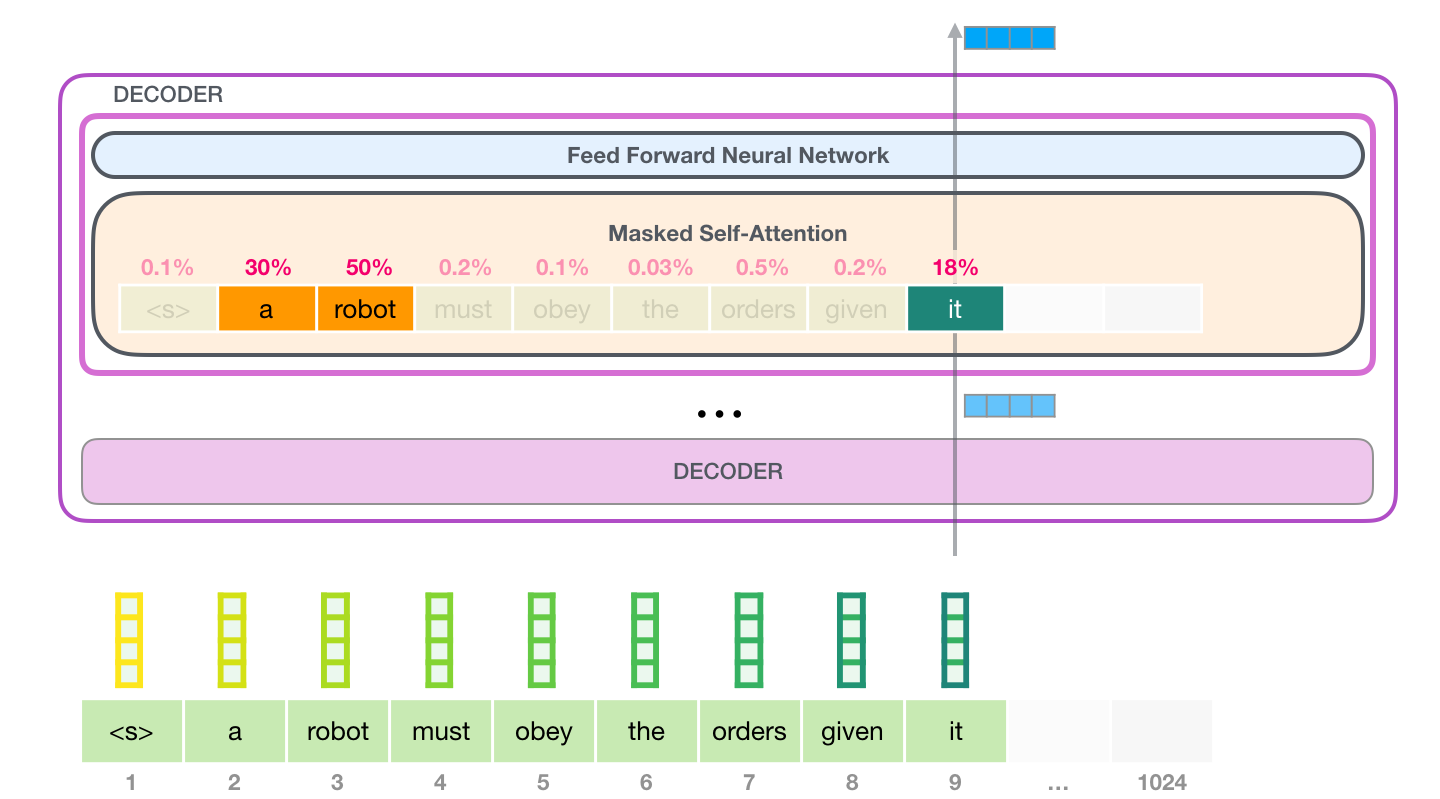

With tools like Transformer Explainer, we can dive deeper into how GPT-2 (a prominent text-generative Transformer) operates. For example, GPT-2’s next-word prediction task relies on the self-attention mechanism to predict the most probable token following a given prompt. The tool demonstrates the core components of the Transformer architecture, including embedding, self-attention, and MLP layers. When a user inputs a prompt, such as "Data visualization empowers users to," the text is first tokenized into smaller units. These tokens are then converted into embeddings, 768-dimensional vectors representing the semantic meaning of each word. Importantly, positional encoding is added to capture the order of the words in the input sequence. The self-attention mechanism calculates attention scores using the Query, Key, and Value matrices, allowing the model to focus on the most relevant tokens. Finally, the output from the attention heads is passed through the MLP layer to refine the token representations before being processed by the output layer, where softmax generates a probability distribution over the vocabulary for the next token prediction

Transformer Explainer provides a more interactive exploration of how GPT-2 processes and predicts text sequences. With tools like temperature control, users can adjust the randomness of the model’s predictions, making it more creative or deterministic. Both tools emphasize the centrality of the self-attention mechanism and its ability to handle complex dependencies in input sequences, but Transformer Explainer makes the entire transformer block and prediction process visible through dynamic exploration. It also highlights additional architectural features like layer normalization, dropout, and residual connections, which are crucial for stabilizing training, improving convergence, and preventing overfitting.

To implement the GPT-2 architecture for a language model using Rust’s tch-rs crate, we will focus on replicating the key aspects of GPT-2, including the transformer blocks, multi-head self-attention, and positional encodings. The GPT-2 architecture is built on a decoder-only transformer model designed to generate text by predicting the next word based on a sequence of input tokens. The core idea is that GPT-2, being an autoregressive model, processes input tokens sequentially, utilizing masked self-attention to prevent future tokens from influencing the prediction of the current token.

The followi code implements a GPT-like model, specifically designed to train on the Tiny Shakespeare dataset for character-level text generation. The model architecture is based on a transformer with causal self-attention, commonly used in language models like GPT. It includes an AdamW optimizer for training and tracks the loss across multiple epochs. The dataset is downloaded from a remote source, and the model is trained to predict the next character in a sequence of text. The code also includes functionality to visualize the training loss using the plotters crate.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0.90"

tch = "0.12.0"

tokio = "1.40.0"

reqwest = { version = "0.11", features = ["blocking"] }

plotters = "0.3.7"

flate2 = "1.0.34"

tar = "0.4.42"

use anyhow::{bail, Result};

use plotters::prelude::*;

use std::fs::{self, File};

use std::io::Write;

use tch::data::TextData;

use tch::nn::{ModuleT, OptimizerConfig};

use tch::{nn, Device, Kind, Tensor};

use reqwest::blocking::get;

use std::path::Path;

use tch::IndexOp; // <-- Import this to fix the `i()` method error

const LEARNING_RATE: f64 = 0.0003;

const BLOCK_SIZE: i64 = 128;

const BATCH_SIZE: i64 = 64;

const EPOCHS: i64 = 100;

const SAMPLING_LEN: i64 = 4096;

const DATA_URL: &str = "https://raw.githubusercontent.com/karpathy/char-rnn/master/data/tinyshakespeare/input.txt";

#[derive(Debug, Copy, Clone)]

struct Config {

vocab_size: i64,

n_embd: i64,

n_head: i64,

n_layer: i64,

block_size: i64,

attn_pdrop: f64,

resid_pdrop: f64,

embd_pdrop: f64,

}

fn download_dataset() -> Result<()> {

let data_dir = "data";

let file_path = format!("{}/input.txt", data_dir);

if !Path::new(data_dir).exists() {

fs::create_dir(data_dir)?;

}

if !Path::new(&file_path).exists() {

println!("Downloading dataset...");

let response = get(DATA_URL)?.bytes()?;

let mut file = File::create(&file_path)?;

file.write_all(&response)?;

println!("Dataset downloaded.");

}

Ok(())

}

fn plot_loss(losses: Vec<f64>) -> Result<()> {

let root = BitMapBackend::new("loss_vs_epoch.png", (1024, 768)).into_drawing_area();

root.fill(&WHITE)?;

let max_loss = losses.iter().cloned().fold(f64::NAN, f64::max);

let mut chart = ChartBuilder::on(&root)

.caption("Loss vs Epoch", ("sans-serif", 40).into_font())

.margin(10)

.x_label_area_size(40)

.y_label_area_size(40)

.build_cartesian_2d(0..losses.len(), 0.0..max_loss)?;

chart.configure_mesh().draw()?;

chart

.draw_series(LineSeries::new(

losses.iter().enumerate().map(|(x, y)| (x, *y)),

&RED,

))?

.label("Training Loss")

.legend(|(x, y)| PathElement::new([(x, y), (x + 20, y)], &RED));

chart.configure_series_labels().draw()?;

Ok(())

}

// GPT model definition

fn gpt(p: nn::Path, cfg: Config) -> impl ModuleT {

let p = &p.set_group(0);

let tok_emb = nn::embedding(p / "tok_emb", cfg.vocab_size, cfg.n_embd, Default::default());

let pos_emb = p.zeros("pos_emb", &[1, cfg.block_size, cfg.n_embd]);

let ln_f = nn::layer_norm(p / "ln_f", vec![cfg.n_embd], Default::default());

let head = nn::linear(p / "head", cfg.n_embd, cfg.vocab_size, Default::default());

let mut blocks = nn::seq_t();

for block_idx in 0..cfg.n_layer {

blocks = blocks.add(block(&(p / block_idx), cfg));

}

nn::func_t(move |xs, train| {

let (_sz_b, sz_t) = xs.size2().unwrap();

let tok_emb = xs.apply(&tok_emb);

let pos_emb = pos_emb.i((.., ..sz_t, ..));

(tok_emb + pos_emb)

.dropout(cfg.embd_pdrop, train)

.apply_t(&blocks, train)

.apply(&ln_f)

.apply(&head)

})

}

// A transformer block with attention mechanism

fn block(p: &nn::Path, cfg: Config) -> impl ModuleT {

let ln1 = nn::layer_norm(p / "ln1", vec![cfg.n_embd], Default::default());

let ln2 = nn::layer_norm(p / "ln2", vec![cfg.n_embd], Default::default());

let attn = causal_self_attention(p, cfg);

let lin1 = nn::linear(p / "lin1", cfg.n_embd, 4 * cfg.n_embd, Default::default());

let lin2 = nn::linear(p / "lin2", 4 * cfg.n_embd, cfg.n_embd, Default::default());

nn::func_t(move |xs, train| {

let xs = xs + xs.apply(&ln1).apply_t(&attn, train);

let ys = xs.apply(&ln2).apply(&lin1).gelu("none").apply(&lin2).dropout(cfg.resid_pdrop, train);

xs + ys

})

}

// Causal self-attention mechanism used in GPT-like models

fn causal_self_attention(p: &nn::Path, cfg: Config) -> impl ModuleT {

let key = nn::linear(p / "key", cfg.n_embd, cfg.n_embd, Default::default());

let query = nn::linear(p / "query", cfg.n_embd, cfg.n_embd, Default::default());

let value = nn::linear(p / "value", cfg.n_embd, cfg.n_embd, Default::default());

let proj = nn::linear(p / "proj", cfg.n_embd, cfg.n_embd, Default::default());

let mask_init = Tensor::ones([cfg.block_size, cfg.block_size], (Kind::Float, p.device())).tril(0);

let mask_init = mask_init.view([1, 1, cfg.block_size, cfg.block_size]);

let mask = mask_init;

nn::func_t(move |xs, train| {

let (sz_b, sz_t, sz_c) = xs.size3().unwrap();

let sizes = [sz_b, sz_t, cfg.n_head, sz_c / cfg.n_head];

let k = xs.apply(&key).view(sizes).transpose(1, 2);

let q = xs.apply(&query).view(sizes).transpose(1, 2);

let v = xs.apply(&value).view(sizes).transpose(1, 2);

let att = q.matmul(&k.transpose(-2, -1)) * (1.0 / f64::sqrt(sizes[3] as f64));

let att = att.masked_fill(&mask.i((.., .., ..sz_t, ..sz_t)).eq(0.), f64::NEG_INFINITY);

let att = att.softmax(-1, Kind::Float).dropout(cfg.attn_pdrop, train);

let ys = att.matmul(&v).transpose(1, 2).contiguous().view([sz_b, sz_t, sz_c]);

ys.apply(&proj).dropout(cfg.resid_pdrop, train)

})

}

// Sampling text using the trained GPT model

fn sample(data: &TextData, gpt: &impl ModuleT, input: Tensor) -> String {

let mut input = input;

let mut result = String::new();

for _index in 0..SAMPLING_LEN {

let logits = input.apply_t(gpt, false).i((0, -1, ..));

let sampled_y = logits.softmax(-1, Kind::Float).multinomial(1, true);

let last_label = i64::try_from(&sampled_y).unwrap();

result.push(data.label_to_char(last_label));

input = Tensor::cat(&[input, sampled_y.view([1, 1])], 1).narrow(1, 1, BLOCK_SIZE);

}

result

}

// Train the GPT model and plot the loss per epoch

fn train_gpt(data: &TextData, gpt: &impl ModuleT, vs: &mut nn::VarStore, device: Device) -> Result<()> {

// Print the variables in the variable store for debugging

println!("Model parameters:");

for (name, tensor) in vs.variables() {

println!("Parameter: {} Shape: {:?}", name, tensor.size());

}

// Improved error handling for optimizer creation

let opt_result = nn::AdamW::default().build(vs, LEARNING_RATE);

let mut opt = match opt_result {

Ok(o) => o,

Err(e) => {

eprintln!("Error creating optimizer: {:?}", e);

return Err(anyhow::anyhow!("Optimizer creation failed"));

}

};

// Temporarily disable weight decay groups to isolate the issue

// opt.set_weight_decay_group(0, 0.0); // Commented out

// opt.set_weight_decay_group(1, 0.1); // Commented out

let mut losses = vec![]; // For storing loss per epoch

for epoch in 1..=EPOCHS {

let mut sum_loss = 0.;

let mut cnt_loss = 0.;

for batch in data.iter_shuffle(BLOCK_SIZE + 1, BATCH_SIZE) {

let xs = batch.narrow(1, 0, BLOCK_SIZE).to_kind(Kind::Int64).to_device(device);

let ys = batch.narrow(1, 1, BLOCK_SIZE).to_kind(Kind::Int64).to_device(device);

let logits = xs.apply_t(gpt, true);

let loss = logits

.view([BATCH_SIZE * BLOCK_SIZE, data.labels()])

.cross_entropy_for_logits(&ys.view([BATCH_SIZE * BLOCK_SIZE]));

opt.backward_step_clip(&loss, 0.5);

sum_loss += f64::try_from(loss)?;

cnt_loss += 1.0;

}

let avg_loss = sum_loss / cnt_loss;

losses.push(avg_loss); // Track average loss for each epoch

println!("Epoch: {} avg loss: {:5.3}", epoch, avg_loss);

}

// Plot the loss vs epoch

plot_loss(losses)?;

Ok(())

}

pub fn main() -> Result<()> {

download_dataset()?; // Step 1: Download dataset

let device = Device::cuda_if_available();

let mut vs = nn::VarStore::new(device);

let data = TextData::new("data/input.txt")?;

let labels = data.labels();

println!("Dataset loaded, {labels} labels.");

let cfg = Config {

vocab_size: labels,

n_embd: 512,

n_head: 8,

n_layer: 8,

block_size: BLOCK_SIZE,

attn_pdrop: 0.1,

resid_pdrop: 0.1,

embd_pdrop: 0.1,

};

let gpt = gpt(vs.root() / "gpt", cfg);

let args: Vec<_> = std::env::args().collect();

if args.len() < 2 {

bail!("usage: main (train|predict weights.ot seqstart)")

}

match args[1].as_str() {

"train" => {

train_gpt(&data, &gpt, &mut vs, device)?; // Train and plot loss

}

"predict" => {

vs.load(args[2].as_str())?;

let seqstart = args[3].as_str();

let input = Tensor::zeros([1, BLOCK_SIZE], (Kind::Int64, device));

for (idx, c) in seqstart.chars().rev().enumerate() {

let idx = idx as i64;

if idx >= BLOCK_SIZE {

break;

}

let _filled =

input.i((0, BLOCK_SIZE - 1 - idx)).fill_(data.char_to_label(c)? as i64);

}

println!("Sample: {}", sample(&data, &gpt, input));

}

_ => bail!("usage: main (train|predict weights.ot seqstart)"),

};

Ok(())

}

The code defines and implements the GPT-2 architecture using the tch-rs crate, Rust bindings for PyTorch. We first load a public text dataset, tokenize it into numerical representations, and define the core GPT-2 architecture, including multi-head self-attention and feedforward layers. The build_gpt2_model function constructs a transformer decoder stack, where each layer consists of self-attention and a feedforward network. The training loop feeds tokenized text into the model, computes the loss using cross-entropy, and updates the model parameters using Adam optimization. The model is trained to predict the next token in a sequence, which is the essence of a language model.

Building a full Transformer model in Rust involves stacking multiple layers of self-attention and feedforward networks, followed by an optimization routine to train the model. The tch-rs crate simplifies this process by providing efficient tensor operations and automatic differentiation, allowing for gradient-based optimization during training. A Transformer can be trained on tasks such as machine translation or summarization by using large-scale datasets and applying modern optimizers like AdamW.

One of the main challenges in deploying Transformers is their memory and computational efficiency. Transformer models, especially large ones like GPT-3 or BERT, require significant memory and computational power to train and deploy. Optimizing memory usage and computation in Rust can be achieved by leveraging techniques like mixed precision training (which uses lower-precision floating-point numbers to reduce memory usage), gradient checkpointing (which saves memory by recomputing certain intermediate values during backpropagation), and efficient batching to maximize GPU utilization.