Chapter 2

Mathematical Foundations for LLMs

"The future of AI depends on the fusion of powerful algorithms and the mathematical understanding that underpins them." — Andrew Ng

Chapter 1 of LMVR lays the mathematical groundwork essential for understanding and implementing large language models (LLMs). The chapter delves into the critical areas of linear algebra, probability and statistics, calculus and optimization, information theory, linear transformations, and discrete mathematics. It covers fundamental concepts such as vectors, matrices, probability distributions, gradients, and entropy, building up to more advanced topics like eigen decomposition, principal component analysis (PCA), and graph theory. These mathematical principles are contextualized within Rust, emphasizing the practical implementation of algorithms, optimization techniques, and data structures essential for efficient LLM development. By integrating theory with hands-on coding practices in Rust, this chapter equips readers with a robust, comprehensive, and precise understanding of the mathematical foundations necessary for LLMs.

2.1. Linear Algebra and Vector Spaces

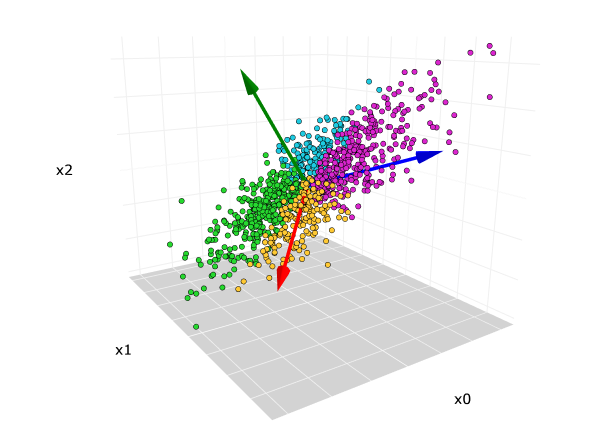

Linear algebra plays a central role in the design and functioning of Large Language Models (LLMs), underpinning the mathematics of how data is represented and transformed within these models. At the core of this foundation are scalars, vectors, matrices, and tensors, which represent the building blocks of data manipulation. A scalar is a single numerical value, while a vector is a one-dimensional array of numbers. When you extend this concept to two dimensions, you have a matrix, and a tensor generalizes this to even higher dimensions. In the context of LLMs, tensors are crucial as they represent the multi-dimensional data required to model language, where each dimension might encode different properties, such as word embeddings, sentence structures, or even entire sequences of text.

In the language of linear algebra, vector spaces provide a formal framework to understand how data points (vectors) are structured and transformed. A vector space consists of a collection of vectors that can be scaled and added together to form new vectors. Within this, a subspace is a smaller vector space contained within a larger one, and this concept is essential when reducing the dimensionality of large datasets. For example, when training an LLM, the subspace of frequently used words might be more critical for attention mechanisms than the entire vector space. The basis of a vector space is a minimal set of vectors from which all vectors in the space can be formed through linear combinations. The dimension of a vector space is the number of vectors in this basis, and for LLMs, this could correspond to the number of unique tokens (words or subwords) that the model processes.

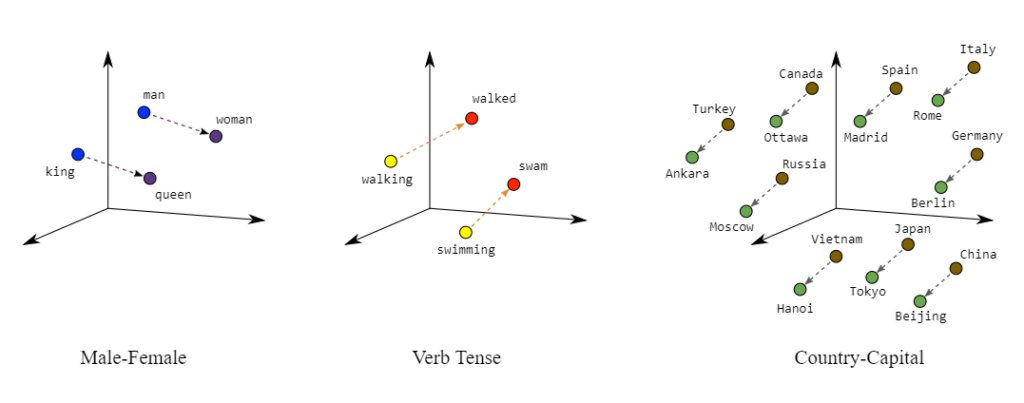

Figure 1: Illustration of vector space for NLP.

Important properties of vector spaces, such as linear independence and span, directly affect how well an LLM can learn meaningful relationships between words. A set of vectors is linearly independent if no vector in the set can be written as a combination of others, which means each vector adds unique information. This is a desirable property in word embeddings, where each word's vector should capture different semantic information. The span of a set of vectors represents all possible vectors that can be formed by linearly combining the set. In practical applications, this concept is essential when modeling large corpora of text, where the span of word embeddings must cover the semantic relationships between words in the language.

Matrix operations are the mathematical manipulations that power LLM computations. Matrix addition and multiplication are fundamental when transforming data between layers in a model. For example, given two matrices $A$ and $B$, matrix addition results in a new matrix $C$ where each element $C_{ij} = A_{ij} + B_{ij}$, and multiplication is given by $C_{ij} = \sum_k A_{ik} B_{kj}$, which is used extensively in transforming input data through various layers in a neural network. Operations like the transpose of a matrix, where rows and columns are swapped, are critical for operations like dot-product attention in Transformer models. Understanding how matrices interact is vital for grasping how data flows through models, especially when working with complex architectures like Transformers in LLMs.

Matrices also have properties like inverses and determinants, which are fundamental in solving systems of linear equations, though their usage in LLMs is more abstract. The inverse of a matrix $A$ is another matrix $A^{-1}$ such that $A A^{-1} = I$ (where $I$ is the identity matrix), and the determinant provides insights into the matrix's properties, such as whether it is invertible. More importantly for LLMs, the concepts of eigenvalues and eigenvectors provide the mathematical basis for dimensionality reduction techniques, such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA), which are used in preprocessing steps for reducing the complexity of word embeddings or other features. Formally, if a matrix $A$ acts on a vector $v$, the vector only gets scaled by a scalar $\lambda$, meaning $A v = \lambda v$. The scalar $\lambda$ is the eigenvalue, and the vector $v$ is the eigenvector. This principle helps in extracting the most significant directions (or components) in a dataset, which directly aids LLM performance by focusing on the most important features.

Another important concept in LLMs is orthogonalization and orthonormal bases. Two vectors are orthogonal if their dot product is zero, and an orthogonal basis allows for easy transformations and simplifications in matrix computations. An orthonormal basis is a set of orthogonal vectors that also have unit length. In practice, many algorithms like Gram-Schmidt are used to orthogonalize vectors, simplifying transformations in LLM computations, especially in methods like singular value decomposition (SVD), which is used in dimensionality reduction.

Matrix operations are fundamental to the implementation of large language models (LLMs), where tasks such as attention mechanisms, token embeddings, and backpropagation rely heavily on efficient handling of multi-dimensional arrays. In Rust, the nalgebra crate provides robust support for such operations, allowing us to work with vectors, matrices, and tensors required for the underlying computations in LLMs. Advanced operations such as matrix multiplication, element-wise products, transposition, inversion, and dot products are essential to optimize and scale deep learning models, particularly in tasks where large-scale matrix operations need to be efficiently handled for high-performance computing.

use nalgebra as na;

use na::{Matrix2, Vector2, Matrix3, Matrix3x2, DMatrix, SMatrix};

fn main() {

// Example of 2x2 Matrix and 2x1 Vector multiplication

let a = Matrix2::new(1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0);

let b = Vector2::new(5.0, 6.0);

let result = a * b;

println!("Result of matrix-vector multiplication: {}", result);

// Example of 3x3 Matrix and 3x2 Matrix multiplication

let c = Matrix3::new(1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0, 6.0, 7.0, 8.0, 9.0);

let d = Matrix3x2::new(1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0, 6.0);

let result_matrix = c * d;

println!("Result of matrix-matrix multiplication (3x3 * 3x2):\n{}", result_matrix);

// Example of matrix transposition

let transpose = c.transpose();

println!("Transposed matrix:\n{}", transpose);

// Element-wise multiplication (Hadamard product)

let e = Matrix2::new(1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0);

let f = Matrix2::new(0.5, 0.2, 0.3, 0.1);

let hadamard_product = e.component_mul(&f);

println!("Element-wise multiplication (Hadamard product):\n{}", hadamard_product);

// Example of matrix inversion (for 2x2 matrix)

match e.try_inverse() {

Some(inverse) => println!("Inverse of matrix e:\n{}", inverse),

None => println!("Matrix e is not invertible."),

}

// Dot product example

let g = Vector2::new(1.0, 2.0);

let h = Vector2::new(3.0, 4.0);

let dot_product = g.dot(&h);

println!("Dot product of vectors g and h: {}", dot_product);

// Large dynamic matrix multiplication (DMatrix for large dynamic sizes)

let matrix1 = DMatrix::from_vec(4, 4, vec![

1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0,

5.0, 6.0, 7.0, 8.0,

9.0, 10.0, 11.0, 12.0,

13.0, 14.0, 15.0, 16.0,

]);

let matrix2 = DMatrix::from_vec(4, 4, vec![

1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0,

0.0, 1.0, 0.0, 0.0,

0.0, 0.0, 1.0, 0.0,

0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0,

]);

let large_result = matrix1 * matrix2;

println!("Result of large dynamic matrix multiplication:\n{}", large_result);

// Example of fixed size matrices (SMatrix)

let smatrix_a = SMatrix::<f64, 2, 2>::new(1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0);

let smatrix_b = SMatrix::<f64, 2, 2>::new(5.0, 6.0, 7.0, 8.0);

let smatrix_result = smatrix_a * smatrix_b;

println!("Result of fixed-size matrix multiplication:\n{}", smatrix_result);

}

The provided code demonstrates a range of matrix operations using the nalgebra crate, focusing on tasks relevant to LLMs. First, matrix-vector multiplication is performed, followed by matrix-matrix multiplication to showcase how larger input data can be processed. Transposition is used to reorient the matrices, a common requirement during gradient computation in backpropagation. Element-wise multiplication (Hadamard product) is highlighted to illustrate how corresponding elements of matrices are combined in specific neural network layers. Additionally, matrix inversion is included for solving linear systems. The code further demonstrates dynamic matrix multiplication using DMatrix, which handles matrices of variable sizes, critical for real-world applications where input dimensions may vary. Finally, it shows how to use fixed-size matrices with SMatrix for scenarios where compile-time optimizations can be leveraged. These operations form the backbone of computations in LLM architectures such as Transformers, enabling the model to process and learn from vast text datasets.

One of the biggest challenges in working with large models is efficient memory management. When dealing with matrices and tensors of very large sizes, such as the ones encountered in LLMs, it is important to optimize how memory is allocated and deallocated. Rust’s ownership and borrowing model, combined with libraries like nalgebra and tch, ensures that memory is handled safely and efficiently. Rust’s ability to manage memory without a garbage collector means that large matrix operations can be performed without unexpected delays caused by automatic memory management, making it a great choice for implementing LLMs, where performance is critical.

In conclusion, linear algebra is not just a theoretical foundation but a practical tool that powers the core operations of LLMs. From vector spaces to matrix operations, Rust’s system-level features and powerful libraries like nalgebra allow developers to efficiently implement and optimize these operations for real-world applications in LLMs. The use of these principles in tasks like word embeddings and self-attention mechanisms highlights the central role that linear algebra plays in modern NLP models, making it a critical area of study for anyone looking to understand or build LLMs.

2.2. Probability and Statistics

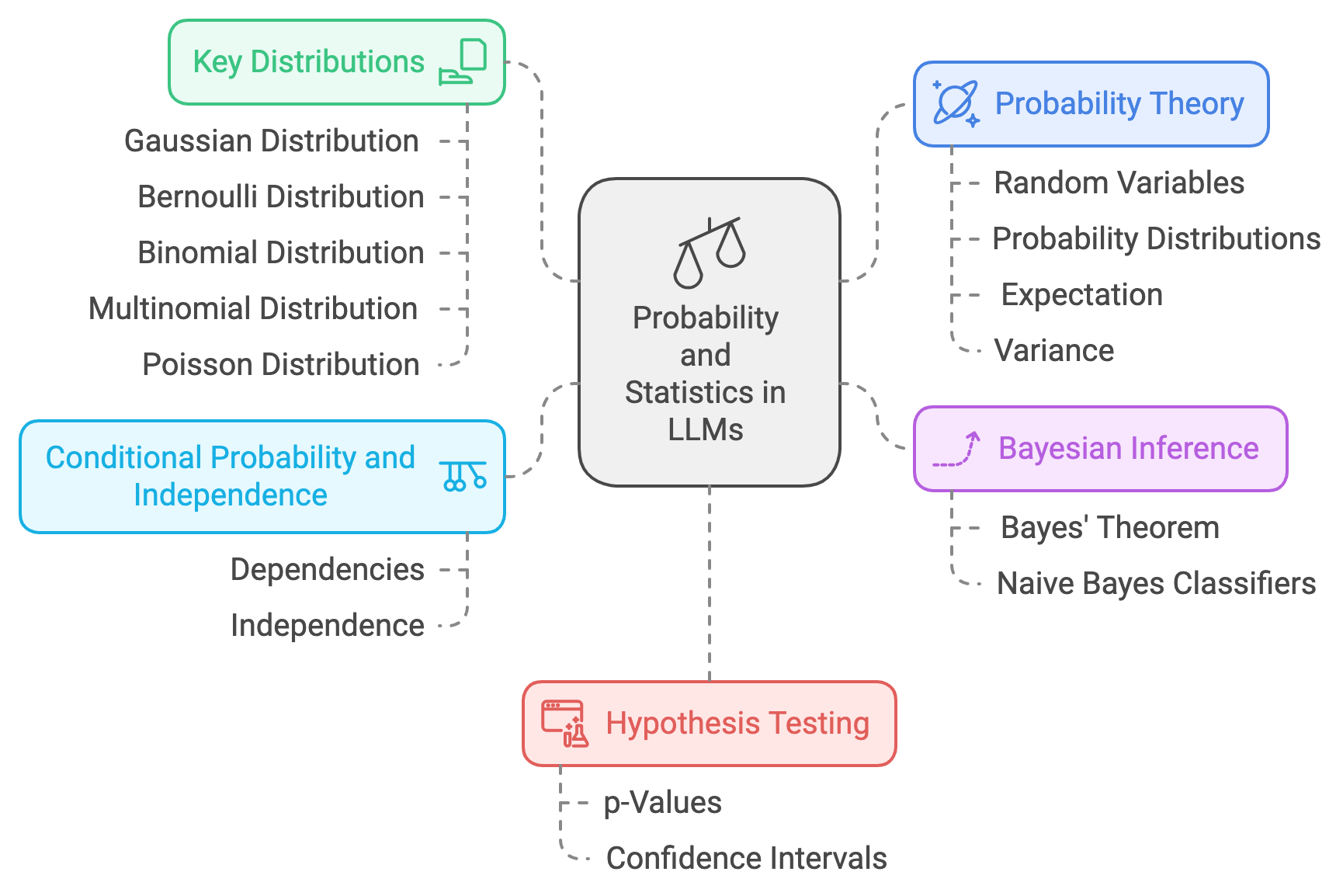

In the world of LLMs, probability and statistics play an essential role in understanding and modeling the uncertainty and randomness inherent in natural language. The foundation of this begins with probability theory, which deals with the study of random variables and the likelihood of different outcomes. A random variable is a variable whose values are outcomes of a random phenomenon, and it can be discrete (taking specific values like the outcome of a dice roll) or continuous (taking any value within a range, such as temperature). Probability distributions describe how likely it is for a random variable to take specific values. Important concepts such as expectation (the average or expected value of a random variable) and variance (a measure of how spread out the values of the random variable are) are crucial for understanding how models process and generate language in an uncertain world.

Figure 2: Roles of probability and statistics in LLMs.

Several important probability distributions are commonly used in LLM development. For instance, the Gaussian distribution (also known as the normal distribution) is central in modeling continuous variables and is widely used due to the Central Limit Theorem, which states that the sum of many independent random variables will tend to follow a Gaussian distribution, regardless of their original distributions. The Bernoulli distribution models binary outcomes, such as yes/no or true/false responses, while the Binomial distribution generalizes this to multiple trials, where we are interested in the number of successes in a fixed number of independent Bernoulli trials. Similarly, the Multinomial distribution extends the Binomial case to scenarios with more than two possible outcomes, which is particularly useful in language models when dealing with multiple classes (e.g., word predictions). Lastly, the Poisson distribution is used to model the number of events occurring within a fixed interval of time or space, which is relevant in NLP tasks like modeling word occurrence frequencies.

Bayesian inference is another key concept in LLMs, providing a framework for updating the probability of a hypothesis as more evidence becomes available. In Bayesian reasoning, the key idea is to update a prior belief (prior probability) with new evidence (likelihood) to obtain a revised belief (posterior probability). Mathematically, this is represented using Bayes' Theorem, which is written as:

$$ P(A | B) = \frac{P(B | A) \cdot P(A)}{P(B)} $$

where $P(A | B)$ is the posterior probability (the probability of event A happening given that B has occurred), $P(B | A)$ is the likelihood (the probability of observing B given that A has happened), $P(A)$ is the prior probability of A, and $P(B)$ is the marginal likelihood. In LLMs, Bayesian inference is used in various ways, such as improving model predictions by incorporating prior knowledge or uncertainty into the model’s decision-making process. Naive Bayes classifiers, for instance, are based on applying Bayes' Theorem with the assumption of independence between features. Though simple, Naive Bayes classifiers are often used in text classification tasks, such as spam detection or sentiment analysis, due to their computational efficiency and interpretability.

Conditional probability and independence are also critical in LLMs. Conditional probability $P(A|B)$ represents the probability of an event A occurring given that event B has already occurred. Understanding the dependencies and relationships between words in a sentence, for example, can be framed in terms of conditional probabilities. Independence occurs when the probability of one event does not affect the probability of another event, which is often an assumption made to simplify complex models (as in the Naive Bayes model). However, in more advanced models like Transformers, understanding dependencies (or lack thereof) between words in a sentence is a complex, but fundamental, part of how LLMs are able to process and generate coherent language.

Hypothesis testing is used to determine whether a result is statistically significant. In LLMs, this is relevant when comparing different models or assessing performance under different experimental conditions. A common tool in hypothesis testing is the p-value, which measures the strength of evidence against the null hypothesis. Confidence intervals provide a range of values that likely contain the true parameter of interest and are widely used in evaluating model performance metrics, such as accuracy or F1 scores. Understanding these statistical tools is important in fine-tuning LLMs and verifying that changes made to a model, such as hyperparameter adjustments, lead to statistically significant improvements.

In LLMs, probabilistic concepts are key to tasks such as generating text, sampling from logits, and regularizing models with noise. This code extends the basic Gaussian sampling to cover a broader set of probabilistic operations that are frequently used in Large Language Models (LLMs). By using a variety of probability distributions (Gaussian, Bernoulli, and Multinomial), we can model uncertainties in prediction tasks and simulate processes such as word generation, classification, and Monte Carlo methods. These operations are essential in LLMs for generating samples from probability distributions, applying the softmax function to model predictions, and using Monte Carlo techniques to estimate expectations.

use rand::thread_rng;

use rand_distr::{Normal, Bernoulli, Distribution};

use statrs::distribution::Multinomial;

use std::f64::consts::E;

// Softmax function implementation

fn softmax(logits: &[f64]) -> Vec<f64> {

let exp_values: Vec<f64> = logits.iter().map(|&x| E.powf(x)).collect();

let sum_exp: f64 = exp_values.iter().sum();

exp_values.iter().map(|&x| x / sum_exp).collect()

}

fn main() {

let mut rng = thread_rng();

// Example 1: Gaussian (Normal) Distribution for continuous random variables

let normal = Normal::new(0.0, 1.0).unwrap(); // Gaussian distribution with mean 0 and variance 1

println!("Gaussian Distribution Samples:");

for _ in 0..10 {

let sample = normal.sample(&mut rng);

println!("Sample: {}", sample);

}

// Example 2: Bernoulli Distribution for binary outcomes

let p_success = 0.7; // Probability of success (e.g., predicting a class in binary classification)

let bernoulli = Bernoulli::new(p_success).unwrap();

println!("\nBernoulli Distribution Samples (p = {}):", p_success);

for _ in 0..10 {

let sample = bernoulli.sample(&mut rng);

println!("Sample (1 = success, 0 = failure): {}", sample);

}

// Example 3: Multinomial Distribution for categorical variables

let probabilities = vec![0.2, 0.5, 0.3]; // Probabilities for categories (e.g., word predictions in LLM)

let multinomial = Multinomial::new(&probabilities, 1).unwrap(); // Number of trials = 1 for a single word prediction

println!("\nMultinomial Distribution Samples (for word prediction probabilities):");

for _ in 0..10 {

let sample = multinomial.sample(&mut rng);

println!("Sample: {:?}", sample);

}

// Example 4: Softmax sampling for LLMs

let logits = vec![2.0, 1.0, 0.1]; // Example logits from an LLM (before softmax)

let softmax_probs = softmax(&logits);

let softmax_multinomial = Multinomial::new(&softmax_probs, 1).unwrap(); // Sampling a word based on softmax probabilities

println!("\nSoftmax-based Sampling (Logits: {:?}):", logits);

for _ in 0..5 {

let sample = softmax_multinomial.sample(&mut rng);

println!("Sample: {:?}", sample);

}

// Example 5: Monte Carlo Estimation using Gaussian distribution

let mut mc_sum = 0.0;

let num_samples = 1000;

for _ in 0..num_samples {

let sample = normal.sample(&mut rng);

mc_sum += sample; // Simulate expectation calculation

}

let mc_estimate = mc_sum / num_samples as f64;

println!("\nMonte Carlo Estimate of Expectation (Gaussian): {}", mc_estimate);

}

The Rust code demonstrates various probability distributions and sampling techniques relevant to large language models (LLMs). It starts by sampling from a Gaussian distribution, often used in tasks requiring continuous random variables, like adding noise or modeling continuous features. It then samples from a Bernoulli distribution, which is used for binary classification tasks, followed by a Multinomial distribution, essential for generating categorical predictions like word selections in LLMs. The code also includes an example of softmax sampling, where logits are converted into probabilities to generate word predictions, mimicking how LLMs make probabilistic predictions. Finally, it implements a Monte Carlo estimation using Gaussian samples to compute an expected value, which is a technique often employed in probabilistic inference or optimization methods within LLMs. These operations are crucial for understanding uncertainty, performing predictions, and sampling efficiently in NLP tasks.When applied to LLMs, probabilistic models help in several key areas. For example, Naive Bayes classifiers can be integrated into LLM pipelines for tasks such as text classification or topic modeling. These models use probability distributions to predict the likelihood that a given document belongs to a particular class (e.g., spam or not spam). By leveraging Rust’s performance and memory safety, probabilistic models can be implemented efficiently, especially when dealing with large datasets that are common in natural language processing. Moreover, probabilistic reasoning is essential in applications like dialog systems, where an LLM might use probabilities to evaluate possible responses based on prior interactions or user input.

The integration of probabilistic reasoning in LLM pipelines has become more prevalent with the rise of techniques like Bayesian Neural Networks (BNNs), which introduce uncertainty into model parameters. BNNs combine the power of deep learning with Bayesian inference, enabling LLMs to output predictions with confidence intervals, which is highly valuable in areas like healthcare or finance, where model uncertainty must be quantified.

Industry use cases are abundant when it comes to applying probability and statistics in LLMs. In healthcare, probabilistic models in LLMs are used to predict disease outcomes based on patient data, where uncertainty and the probabilistic nature of medical records play a crucial role. In finance, LLMs use probability distributions to model market trends, assess risks, and detect anomalies in transaction data. Moreover, with the development of new tools in probabilistic modeling, Rust’s ability to efficiently manage memory and leverage its powerful type system ensures that applications in these fields are safe, scalable, and high-performing.

The latest trends in probabilistic reasoning within LLMs include the integration of uncertainty estimation in model predictions, especially in areas where decision-making under uncertainty is crucial. Tools like Bayesian Optimization are increasingly used in tuning LLMs' hyperparameters, which allows models to be optimized more efficiently, reducing the time and computational resources required to achieve peak performance.

In conclusion, probability and statistics are indispensable in the development and application of LLMs. From the theoretical foundations of probability distributions and Bayes' Theorem to practical implementations using Rust’s crates like rand, the integration of probabilistic reasoning in LLMs is essential for modeling language, understanding uncertainty, and improving decision-making capabilities. Rust’s efficiency, combined with its robust ecosystem for mathematical and probabilistic modeling, provides an excellent environment for building probabilistically sound and high-performance LLM applications in real-world industries.

2.3. Calculus and Optimization

In the development and training of Large Language Models (LLMs), calculus is fundamental, particularly in the context of optimization. Differentiation and integration serve as the mathematical backbone of how models learn by adjusting their parameters to minimize a loss function. In machine learning, we primarily deal with differentiation, which helps in understanding how small changes in model parameters affect the output. For instance, the derivative of a function provides the rate at which the function’s value changes as its input changes. This is key to training LLMs, where we aim to adjust the model’s parameters (weights) to minimize a given error or loss function. Integration, while less frequently used in typical LLM training, plays a role in calculating areas under curves, which can be useful in probabilistic models and Bayesian approaches to model learning.

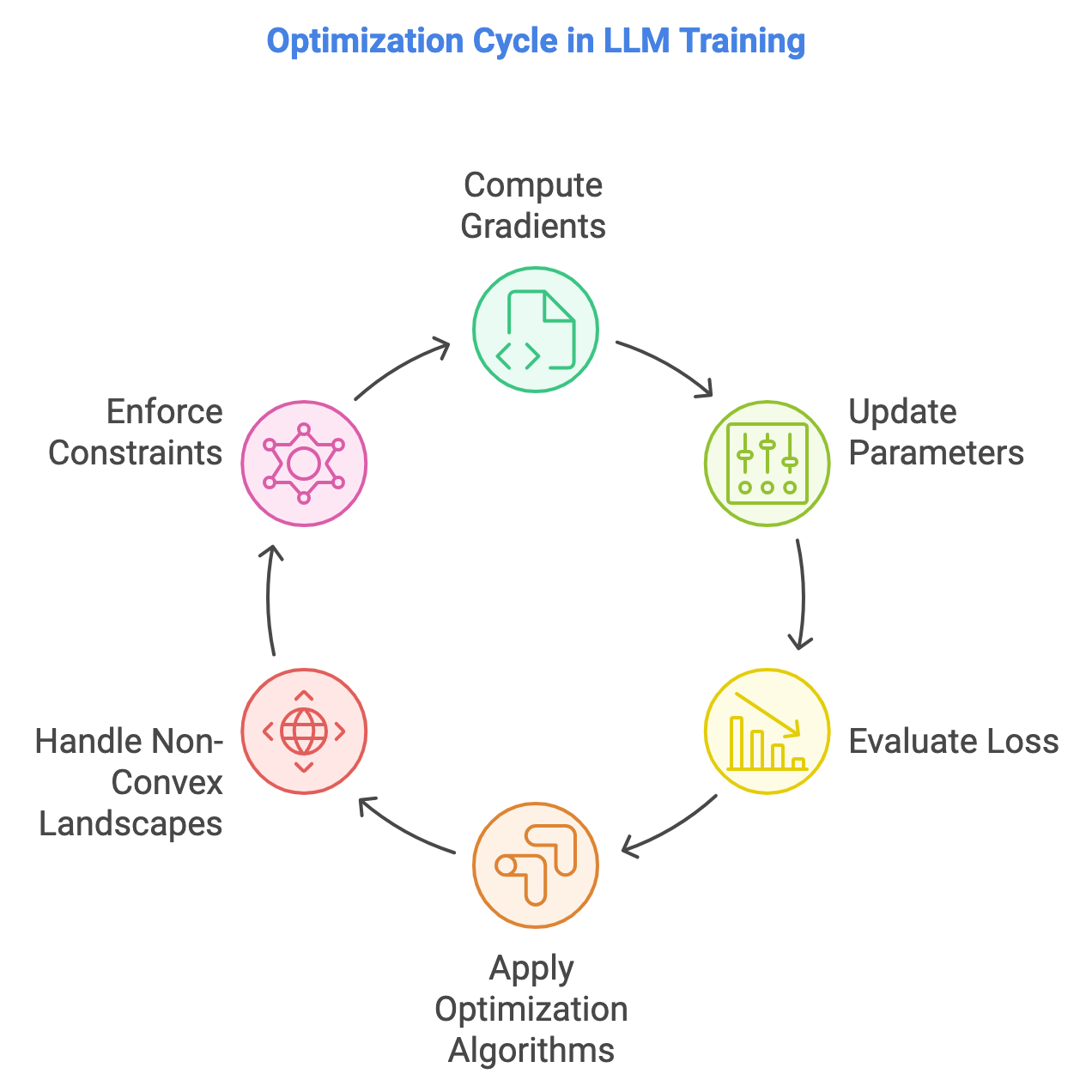

Figure 3: Optimization cycle in training LLMs.

One of the most important concepts in training LLMs is the partial derivative, which is a derivative with respect to one variable while keeping others constant. This is crucial because LLMs have many parameters (sometimes billions), and computing partial derivatives with respect to each parameter is necessary to understand how each individual parameter influences the model's predictions. Gradients, which are vectors of partial derivatives, represent the direction of steepest ascent for a multivariable function, and they are key to optimizing the parameters during training.

The chain rule is essential when working with deep models, where inputs are processed through multiple layers of functions. The chain rule allows us to compute the derivative of a composite function, which is the case in backpropagation, the algorithm used to train deep learning models, including LLMs. Formally, if we have a composite function $f(g(x))$, the chain rule tells us that the derivative of this composition is the derivative of $f$ times the derivative of $g$, written as:

$$\frac{d}{dx} f(g(x)) = f'(g(x)) \cdot g'(x)$$

In LLMs, this is applied across multiple layers, where each layer passes its output to the next, and we need to compute the gradient at each layer to update the model's parameters accordingly. Other useful rules in differentiation include the product rule and quotient rule, which allow us to compute derivatives of functions that are products or quotients of other functions.

In practice, Taylor series provides a way to approximate complex functions with polynomials, making them easier to work with in optimization problems. The Taylor series expansion of a function around a point allows us to approximate the function locally, which can be useful in optimization when evaluating model performance for small perturbations in the input or model parameters.

Optimization is at the heart of training LLMs, and one of the most important methods is gradient descent. In this algorithm, we use the gradient of the loss function to update the model's parameters iteratively. Mathematically, if $\theta$ represents the parameters of the model and $L(\theta)$ represents the loss function, gradient descent updates the parameters as follows:

$$ \theta := \theta - \eta \cdot \nabla_\theta L(\theta) $$

where $\eta$ is the learning rate, and $\nabla_\theta L(\theta)$ is the gradient of the loss function with respect to the parameters. Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) and Mini-batch Gradient Descent are popular variants of this algorithm, where instead of computing the gradient using the entire dataset, we compute it using one sample or a small batch of samples, respectively. This reduces the computational cost per update and allows the model to converge faster in large datasets, such as those used in LLM training.

When dealing with convex optimization problems, gradient descent performs well because convex functions have a single global minimum. However, LLMs often require optimization in non-convex landscapes, where the loss function can have multiple local minima and saddle points. As a result, variants like Adam (Adaptive Moment Estimation) and RMSProp are often used in LLMs. These methods incorporate momentum and adaptive learning rates to handle the challenges posed by non-convex optimization landscapes, helping the model avoid poor local minima and converge more efficiently.

Lagrange multipliers provide a way to perform optimization with constraints. In LLMs, constraints can appear when we impose certain regularization conditions to prevent overfitting, such as limiting the magnitude of the model's weights. If we want to minimize a function $f(x)$ subject to a constraint $g(x) = 0$, the method of Lagrange multipliers introduces an auxiliary variable $\lambda$ and solves:

$$ \nabla f(x) + \lambda \nabla g(x) = 0 $$

This technique is important when working with constrained optimization problems in LLMs, particularly when enforcing properties such as smoothness or sparsity in the model’s weights.

Jacobians and Hessians are matrix representations of the first and second derivatives of multivariable functions, respectively. The Jacobian matrix contains all first-order partial derivatives of a vector-valued function, while the Hessian matrix contains second-order partial derivatives. These matrices are particularly useful in understanding how the loss function behaves locally in the parameter space, guiding optimization algorithms in LLM training. In second-order optimization methods, the Hessian provides valuable information about the curvature of the loss function, allowing for faster convergence than gradient descent alone, albeit with higher computational costs.

Figure 4: Animation of 5 gradient descent methods on a surface: SGD (cyan), Momentum (magenta), AdaGrad (white), RMSProp (green), Adam (blue). Left well is the global minimum; right well is a local minimum.

In the context of training large language models (LLMs), backpropagation is still the core method for adjusting model parameters to minimize the loss function. This process involves the calculation of gradients using calculus, specifically the chain rule, to efficiently propagate error signals backward through the network layers. At each step, the model updates its parameters by moving in the direction opposite to the gradient (the negative gradient) of the loss function with respect to each parameter, ultimately seeking to minimize the loss. This is computationally intensive, especially in LLMs, which contain millions or even billions of parameters across many layers. Efficiently computing gradients and updating parameters is critical for ensuring the scalability of the training process. There are various optimization algorithms used to perform these updates, each with its advantages and trade-offs in terms of convergence speed, memory efficiency, and generalization ability. Below, we introduce several key optimizers commonly used in LLM training: SGD, Momentum, AdaGrad, RMSProp, and Adam.

SGD is the simplest and most fundamental optimization algorithm. It updates the model parameters by taking a step in the direction of the negative gradient of the loss function with respect to the parameters. Formally, the parameter update at each iteration ttt is given by:

$$\theta_{t+1} = \theta_t - \eta \nabla L(\theta_t)$$

where $\theta_t$ is the parameter at iteration $t$, $\eta$ is the learning rate, and $\nabla L(\theta_t)$ is the gradient of the loss function with respect to the parameter $\theta$. While SGD is simple, it has some limitations, such as slow convergence, especially when the gradients oscillate in steep regions of the loss function. It also suffers from noise due to the randomness in minibatch gradient estimation, which can lead to inefficient training for complex models like LLMs.

The Momentum optimizer improves upon basic SGD by incorporating a "velocity" term that helps the optimization process to dampen oscillations and build momentum in directions where the gradient consistently points. The update rule with momentum is:

$$v_{t+1} = \beta v_t + (1 - \beta) \nabla L(\theta_t)$$

$$\theta_{t+1} = \theta_t - \eta v_{t+1}$$

Here, $v_t$ is the velocity, and $\beta$ is a hyperparameter controlling how much of the previous velocity to retain. Momentum helps to accelerate convergence in the right direction by smoothing out noisy gradient updates, which is particularly useful in deep networks like those used in LLMs. It allows faster progress along shallow regions and helps overcome local minima more efficiently than vanilla SGD.

AdaGrad is an adaptive learning rate method that adjusts the learning rate based on the historical gradient information for each parameter. The intuition behind AdaGrad is that parameters which have been updated frequently should have smaller learning rates, while parameters that receive less frequent updates should maintain higher learning rates. The update rule is:

$$g_{t+1} = g_t + \nabla L(\theta_t)^2$$

$$ \theta_{t+1} = \theta_t - \frac{\eta}{\sqrt{g_{t+1}} + \epsilon} \nabla L(\theta_t) $$

where $g_t$ is the accumulated sum of squared gradients, and ϵ\\epsilonϵ is a small term to prevent division by zero. AdaGrad is useful in dealing with sparse gradients, which often appear in LLMs, particularly in tasks with infrequent updates for certain parameters. However, one drawback is that it can accumulate gradients too aggressively, causing the learning rate to shrink excessively over time, which can slow down training.

RMSProp builds on AdaGrad by introducing a moving average over the squared gradients to control the learning rate more effectively. It helps address AdaGrad’s diminishing learning rate problem by keeping the running average of the squared gradients over time, rather than summing them. The update rule is:

$$ E[g^2]_{t+1} = \beta E[g^2]_t + (1 - \beta) \nabla L(\theta_t)^2 $$

$$\theta_{t+1} = \theta_t - \frac{\eta}{\sqrt{E[g^2]_{t+1}} + \epsilon} \nabla L(\theta_t)$$

Here, $E[g^2]$ is the moving average of the squared gradients, and $\beta$ is a hyperparameter that controls how much past gradients contribute to the current update. RMSProp ensures that the learning rate remains adaptive but does not shrink too rapidly, making it effective for training deep networks and handling non-stationary environments where the gradient distribution can change over time. This is especially relevant in LLMs where different layers and parameters may require different learning rates during different phases of training.

Adam is one of the most popular optimization algorithms in modern deep learning, combining the benefits of both momentum and adaptive learning rates (like RMSProp). Adam computes adaptive learning rates for each parameter by maintaining running averages of both the first moment (mean of the gradients) and second moment (variance of the gradients). The update rule for Adam is:

$$m_{t+1} = \beta_1 m_t + (1 - \beta_1) \nabla L(\theta_t)$$

$$ v_{t+1} = \beta_2 v_t + (1 - \beta_2) (\nabla L(\theta_t))^2 $$

$$ \hat{m}_{t+1} = \frac{m_{t+1}}{1 - \beta_1^{t+1}}, \quad \hat{v}_{t+1} = \frac{v_{t+1}}{1 - \beta_2^{t+1}} $$

$$ \theta_{t+1} = \theta_t - \frac{\eta}{\sqrt{\hat{v}_{t+1}} + \epsilon} \hat{m}_{t+1} $$

Here, $m_t$ and $v_t$ are the first and second moment estimates (mean and variance), and $\beta_1$, $\beta_2$ control their decay rates. $\hat{m}$ and $\hat{v}$ are the bias-corrected estimates. Adam adapts the learning rate for each parameter based on the magnitude of its gradient, making it particularly effective in optimizing deep and complex models like LLMs. It handles sparse gradients well and converges faster, which is why it is the optimizer of choice for many state-of-the-art LLMs such as GPT and BERT.

Each of these optimizers has its strengths and trade-offs in terms of convergence speed, robustness, and computational efficiency. SGD is simple but can be inefficient, while Momentum helps to smooth oscillations and speed up convergence. AdaGrad and RMSProp adapt the learning rate based on gradient history, improving performance for sparse and non-stationary environments. Adam, which combines the advantages of both momentum and adaptive learning rates, is the most widely used optimizer in large-scale LLMs due to its ability to handle the complex, non-convex optimization landscapes typical of deep learning models.

The provided code benchmarks the performance of five popular optimization algorithms—SGD, Momentum, AdaGrad, RMSProp, and Adam—commonly used in training large language models (LLMs) and other deep learning architectures. These optimizers are essential for minimizing the loss function during training by adjusting model parameters based on computed gradients. Each optimizer has its unique way of handling gradients, learning rates, and convergence properties, and the code evaluates their performance in terms of execution speed by simulating a simple training loop.

use ndarray::Array1;

use ndarray::Zip;

use std::time::Instant; // Correct import for `Instant`

// SGD optimizer

struct SGD;

impl SGD {

fn update(params: &mut Array1<f64>, grad: &Array1<f64>, learning_rate: f64) {

Zip::from(params)

.and(grad)

.for_each(|param, &g| *param -= learning_rate * g);

}

}

// Momentum optimizer

struct Momentum {

velocity: Array1<f64>,

beta: f64,

}

impl Momentum {

fn new(param_size: usize, beta: f64) -> Momentum {

Momentum {

velocity: Array1::zeros(param_size),

beta,

}

}

fn update(&mut self, params: &mut Array1<f64>, grad: &Array1<f64>, learning_rate: f64) {

Zip::from(&mut self.velocity)

.and(grad)

.for_each(|v, &g| *v = self.beta * *v + (1.0 - self.beta) * g);

Zip::from(params)

.and(&self.velocity)

.for_each(|param, &v| *param -= learning_rate * v);

}

}

// AdaGrad optimizer

struct AdaGrad {

grad_accum: Array1<f64>,

epsilon: f64,

}

impl AdaGrad {

fn new(param_size: usize, epsilon: f64) -> AdaGrad {

AdaGrad {

grad_accum: Array1::zeros(param_size),

epsilon,

}

}

fn update(&mut self, params: &mut Array1<f64>, grad: &Array1<f64>, learning_rate: f64) {

Zip::from(&mut self.grad_accum)

.and(grad)

.for_each(|accum, &g| *accum += g.powi(2));

Zip::from(params)

.and(grad)

.and(&self.grad_accum)

.for_each(|param, &g, &accum| {

*param -= learning_rate * g / (accum.sqrt() + self.epsilon);

});

}

}

// RMSProp optimizer

struct RMSProp {

grad_accum: Array1<f64>,

beta: f64,

epsilon: f64,

}

impl RMSProp {

fn new(param_size: usize, beta: f64, epsilon: f64) -> RMSProp {

RMSProp {

grad_accum: Array1::zeros(param_size),

beta,

epsilon,

}

}

fn update(&mut self, params: &mut Array1<f64>, grad: &Array1<f64>, learning_rate: f64) {

Zip::from(&mut self.grad_accum)

.and(grad)

.for_each(|accum, &g| *accum = self.beta * *accum + (1.0 - self.beta) * g.powi(2));

Zip::from(params)

.and(grad)

.and(&self.grad_accum)

.for_each(|param, &g, &accum| {

*param -= learning_rate * g / (accum.sqrt() + self.epsilon);

});

}

}

// Adam optimizer

struct Adam {

beta1: f64,

beta2: f64,

epsilon: f64,

m: Array1<f64>,

v: Array1<f64>,

t: usize,

}

impl Adam {

fn new(param_size: usize, beta1: f64, beta2: f64, epsilon: f64) -> Adam {

Adam {

beta1,

beta2,

epsilon,

m: Array1::zeros(param_size),

v: Array1::zeros(param_size),

t: 0,

}

}

fn update(&mut self, params: &mut Array1<f64>, grad: &Array1<f64>, learning_rate: f64) {

self.t += 1;

Zip::from(&mut self.m)

.and(grad)

.for_each(|m, &g| *m = self.beta1 * *m + (1.0 - self.beta1) * g);

Zip::from(&mut self.v)

.and(grad)

.for_each(|v, &g| *v = self.beta2 * *v + (1.0 - self.beta2) * g.powi(2));

let m_hat = self.m.mapv(|m| m / (1.0 - self.beta1.powi(self.t as i32)));

let v_hat = self.v.mapv(|v| v / (1.0 - self.beta2.powi(self.t as i32)));

Zip::from(params)

.and(&m_hat)

.and(&v_hat)

.for_each(|param, &m_h, &v_h| {

*param -= learning_rate * m_h / (v_h.sqrt() + self.epsilon);

});

}

}

// Function to simulate training

fn train<F>(

mut params: Array1<f64>,

learning_rate: f64,

num_iterations: usize,

loss_grad: F,

optimizer: &mut dyn FnMut(&mut Array1<f64>, &Array1<f64>, f64),

) -> Array1<f64>

where

F: Fn(&Array1<f64>) -> Array1<f64>,

{

for _ in 0..num_iterations {

let grad = loss_grad(¶ms);

optimizer(&mut params, &grad, learning_rate);

}

params

}

fn main() {

let param_size = 3; // Number of parameters in a simple model

let num_iterations = 10000; // Number of iterations for benchmark

let learning_rate = 0.01;

// Example loss gradient (linear for simplicity, in practice this would be more complex)

let loss_grad = |params: &Array1<f64>| params.mapv(|p| p - 0.5);

// Initial parameters

let params = Array1::from(vec![1.0, 1.0, 1.0]);

// Benchmarking SGD

let start = Instant::now();

let sgd_params = params.clone(); // No need for `mut` as we're not modifying `sgd_params` directly

train(sgd_params.clone(), learning_rate, num_iterations, loss_grad, &mut |p, g, lr| SGD::update(p, g, lr));

let duration = start.elapsed();

println!("SGD duration: {:?}", duration);

// Benchmarking Momentum

let start = Instant::now();

let mut momentum = Momentum::new(param_size, 0.9);

train(params.clone(), learning_rate, num_iterations, loss_grad, &mut |p, g, lr| momentum.update(p, g, lr));

let duration = start.elapsed();

println!("Momentum duration: {:?}", duration);

// Benchmarking AdaGrad

let start = Instant::now();

let mut adagrad = AdaGrad::new(param_size, 1e-8);

train(params.clone(), learning_rate, num_iterations, loss_grad, &mut |p, g, lr| adagrad.update(p, g, lr));

let duration = start.elapsed();

println!("AdaGrad duration: {:?}", duration);

// Benchmarking RMSProp

let start = Instant::now();

let mut rmsprop = RMSProp::new(param_size, 0.9, 1e-8);

train(params.clone(), learning_rate, num_iterations, loss_grad, &mut |p, g, lr| rmsprop.update(p, g, lr));

let duration = start.elapsed();

println!("RMSProp duration: {:?}", duration);

// Benchmarking Adam

let start = Instant::now();

let mut adam = Adam::new(param_size, 0.9, 0.999, 1e-8);

train(params.clone(), learning_rate, num_iterations, loss_grad, &mut |p, g, lr| adam.update(p, g, lr));

let duration = start.elapsed();

println!("Adam duration: {:?}", duration);

}

The code implements each optimizer as a separate struct, defining its update rule for modifying model parameters based on gradient information. The train function simulates a training process by updating parameters over a set number of iterations using a predefined loss gradient function. Each optimizer's performance is benchmarked using Rust's Instant::now() to measure the time taken to complete the training loop. The parameters and gradients are simulated for simplicity, and the code reports the time taken by each optimizer to process the same task. This setup allows for direct comparison of the optimizers, highlighting their computational efficiency in training models with multiple iterations and gradient updates.

To scale gradient computations for large LLMs, Rust's memory safety and concurrency features make it an excellent choice. Efficient multi-threading with Rust’s Rayon crate and GPU support using tch-rs for tensor operations enable large-scale optimization tasks to be performed with high performance. Furthermore, Rust’s ownership model ensures that memory is managed efficiently during training, minimizing the risk of memory leaks or crashes that can occur with other languages when training very large models.

In conclusion, calculus and optimization are vital to the training and functioning of LLMs. Concepts like differentiation, gradient descent, and convex optimization form the backbone of how LLMs learn from data. Implementing these methods in Rust provides several advantages, including efficient memory management, parallel processing capabilities, and the ability to handle large-scale gradient computations safely and efficiently. By leveraging Rust’s performance and safety features, developers can build scalable LLMs that are optimized for modern hardware and capable of handling the computational demands of large datasets and complex architectures.

2.4. Information Theory

Information theory provides a critical mathematical framework for understanding and measuring the uncertainty, compression, and transmission of information. In the context of Large Language Models (LLMs), information theory helps quantify the amount of uncertainty in predictions, the similarity between probability distributions, and the efficiency of communication between model components. The concept of entropy is central to information theory, and it measures the uncertainty or randomness in a random variable. For a discrete random variable $X$ with probability mass function $p(x)$, the entropy is defined as:

$$ H(X) = -\sum_{x \in X} p(x) \log p(x) $$

Entropy can be interpreted as the average amount of information required to describe the outcome of $X$. In LLMs, entropy plays a key role in language model evaluation, as it provides a measure of the model’s uncertainty in predicting the next word in a sequence. A well-trained model with high certainty will have lower entropy, indicating that it can predict future words more confidently, whereas a model with higher entropy is more uncertain.

In machine learning, especially in the training of language models, cross-entropy is one of the most widely used loss functions. It measures the difference between two probability distributions: the true distribution (labels) and the predicted distribution (model outputs). For a set of true labels $y$ and model predictions $\hat{y}$, cross-entropy is defined as:

$$ H(p, q) = -\sum_{i} p(y_i) \log q(y_i) $$

This equation measures the average number of bits needed to encode the true distribution using the predicted distribution. Cross-entropy loss is used in classification tasks to penalize models that assign low probabilities to the correct class, guiding the model toward better predictions during training. In the context of LLMs, cross-entropy loss is used in tasks like language modeling, where the goal is to minimize the distance between the true probability distribution of the next word in a sentence and the predicted probability distribution from the model.

Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence is another important concept in information theory that quantifies how one probability distribution diverges from a second, reference probability distribution. For two probability distributions $P$ and $Q$, the KL divergence from $Q$ to $P$ is given by:

$$ D_{KL}(P || Q) = \sum_{x} P(x) \log \frac{P(x)}{Q(x)} $$

KL divergence is always non-negative and is zero only when the distributions $P$ and $Q$ are identical. In the context of LLM training, KL divergence is often used in Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) to enforce that the learned latent variables follow a prior distribution. By minimizing KL divergence, the model ensures that its learned distribution does not deviate too far from the prior distribution, making it a critical component in generative models.

Shannon's Theorems, which form the bedrock of modern information theory, establish limits on the efficiency of data compression and transmission. Shannon’s entropy theorem provides a bound on the average length of the shortest possible encoding of a message, while Shannon’s channel coding theorem sets the upper limit of error-free communication over a noisy channel. In LLMs, these theorems are relevant to how models compress and represent information. For example, the ability of an LLM to generate coherent language stems from its ability to encode vast amounts of language data efficiently.

Information-theoretic approaches to regularization are gaining prominence in the training of LLMs. Regularization helps prevent overfitting by constraining the complexity of the model. Information theory offers a way to think about this by quantifying the amount of information a model encodes about its training data. One approach to regularization is to minimize the mutual information between the model parameters and the training data, which limits the model's capacity to memorize the training data and forces it to generalize better. This is particularly important for large-scale models, which are prone to overfitting on vast datasets.

From a practical perspective, information-theoretic measures such as entropy, cross-entropy, and KL divergence can be implemented in Rust to optimize model training and evaluation. Rust’s performance and memory safety features make it an excellent choice for these computational tasks, where numerical stability and efficient memory usage are critical. For example, calculating cross-entropy loss in Rust using a numerical library like ndarray allows us to efficiently perform matrix operations on large datasets, ensuring that training scales well to large models.

In training large language models (LLMs), efficiently computing information-theoretic measures like cross-entropy loss and KL divergence is crucial for optimizing model performance and ensuring numerical stability during training. These metrics directly affect how model parameters are updated and how well the model aligns with its target distributions. Rust, with its strong performance and memory safety features, is an excellent choice for handling these computationally intensive tasks, especially when dealing with large datasets and high-dimensional matrix operations. The use of libraries like ndarray ensures efficient matrix handling while maintaining the precision required for such operations.

use ndarray;

use ndarray::{Array1, Array2, Axis};

// Numerically stable log-softmax function for use in cross-entropy loss

fn log_softmax(pred: &Array1<f64>) -> Array1<f64> {

let max_val = pred.fold(f64::NEG_INFINITY, |a, &b| a.max(b));

let exp_sum = pred.mapv(|x| (x - max_val).exp()).sum();

pred.mapv(|x| (x - max_val) - exp_sum.ln())

}

// Cross-entropy loss for a batch of true labels and predictions

fn cross_entropy_loss(y_true: &Array2<f64>, y_pred: &Array2<f64>) -> f64 {

let mut total_loss = 0.0;

for (true_row, pred_row) in y_true.axis_iter(Axis(0)).zip(y_pred.axis_iter(Axis(0))) {

let log_prob = log_softmax(&pred_row.to_owned());

total_loss += -true_row.dot(&log_prob);

}

total_loss / y_true.nrows() as f64

}

// KL divergence function with added numerical stability

fn kl_divergence(p: &Array1<f64>, q: &Array1<f64>) -> f64 {

p.iter().zip(q.iter())

.map(|(pi, qi)| if *pi > 0.0 { pi * (pi / qi.max(1e-10)).ln() } else { 0.0 })

.sum()

}

// Main function demonstrating usage

fn main() {

// Example: Cross-entropy with mini-batch of true labels and predictions

let y_true = Array2::from_shape_vec((2, 3), vec![1.0, 0.0, 0.0, // Batch 1

0.0, 1.0, 0.0]) // Batch 2

.unwrap();

let y_pred = Array2::from_shape_vec((2, 3), vec![0.7, 0.2, 0.1, // Batch 1

0.4, 0.5, 0.1]) // Batch 2

.unwrap();

let loss = cross_entropy_loss(&y_true, &y_pred);

println!("Cross-entropy loss (batch): {}", loss);

// Example: KL divergence between two distributions

let p = Array1::from(vec![0.6, 0.3, 0.1]);

let q = Array1::from(vec![0.5, 0.4, 0.1]);

let kl_div = kl_divergence(&p, &q);

println!("KL divergence: {}", kl_div);

}

The provided Rust code implements advanced versions of cross-entropy loss and KL divergence, integrating batch processing and numerical stability techniques essential for LLMs. In the cross-entropy loss function, the softmax operation is stabilized by subtracting the maximum value from the predictions before applying the logarithm, preventing overflow and underflow issues. This approach is particularly important in LLMs, where the output space can be extremely large, leading to numerical instability in raw calculations. Additionally, the batch processing capability allows for efficient computation across multiple data points in a mini-batch, a common scenario in LLM training. Similarly, the KL divergence function includes a safeguard against division by zero, ensuring stable performance when comparing probability distributions. These implementations are designed to scale well with large datasets, making them suitable for real-world applications like training transformers and other LLM architectures.

The latest trends in applying information theory to LLMs include information bottleneck methods, which aim to compress representations while retaining only the most essential information. This method is inspired by Shannon's work on compressing communication signals and is now being applied to reduce the complexity of LLMs without sacrificing performance. By minimizing mutual information between the input and hidden representations, models can be made more robust and less prone to overfitting.

Additionally, entropy regularization is becoming a common technique in reinforcement learning and LLMs, where entropy is added to the loss function to encourage exploration in predictions. In practice, this prevents the model from becoming too confident in its predictions, fostering diversity in output generation, which is crucial for tasks such as creative text generation or machine translation.

In conclusion, information theory offers a powerful set of tools for evaluating and optimizing LLMs. Entropy, KL divergence, and cross-entropy loss are essential measures that help guide model training, ensure probabilistic consistency, and enhance model performance. Rust, with its robust computational libraries and efficient memory handling, is an ideal language for implementing these techniques at scale. By understanding and applying information-theoretic principles, we can develop more efficient, robust, and scalable LLMs capable of handling the complexity and diversity of natural language.

2.5. Linear Transformations and Eigen Decomposition

In the context of Large Language Models (LLMs), linear transformations play a crucial role in how input data is manipulated, transformed, and represented within the various layers of the model. A linear transformation is a mathematical function that maps one vector space to another while preserving the operations of vector addition and scalar multiplication. In matrix form, a linear transformation is represented by multiplying a matrix by a vector, where the matrix defines how the space is transformed. For instance, in neural networks, the weights in each layer act as a linear transformation applied to the input vectors, projecting them into new feature spaces. Understanding the properties of these transformations is fundamental in optimizing the model's performance and ensuring that the transformation captures meaningful relationships in the data.

Matrix decomposition is another vital concept, involving breaking down a matrix into simpler, more manageable components. Decomposition techniques such as LU decomposition (which factors a matrix into a lower and upper triangular matrix), QR decomposition (which factors a matrix into an orthogonal matrix and an upper triangular matrix), and Cholesky decomposition (which factors a symmetric positive-definite matrix into a product of a lower triangular matrix and its transpose) are commonly used in numerical linear algebra. These techniques are essential for solving systems of equations, inverting matrices, and optimizing the efficiency of large-scale matrix operations during the training and inference of LLMs.

Eigenvalues and eigenvectors are central to understanding the behavior of linear transformations. Given a matrix $A$, if there exists a scalar $\lambda$ and a non-zero vector $v$ such that: $A v = \lambda v$, then $\lambda$ is called an eigenvalue of $A$ and $v$ is its corresponding eigenvector. The geometric interpretation is that the transformation defined by $A$ only stretches or shrinks the eigenvector vvv, without changing its direction. Diagonalization is the process of converting a matrix into a diagonal form using its eigenvalues and eigenvectors, making computations more efficient and providing insights into the structure of the transformation. For LLMs, eigen decomposition helps in tasks like dimensionality reduction, as it captures the directions of maximal variance in the data, which are often the most informative.

One of the most powerful matrix decomposition techniques is Singular Value Decomposition (SVD), which generalizes eigen decomposition to all matrices (including non-square matrices). SVD breaks a matrix $A$ into three matrices $A = U \Sigma V^T$, where $U$ and $V$ are orthogonal matrices and $\Sigma$ is a diagonal matrix containing the singular values of $A$. SVD is crucial in tasks like Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA), where it helps in identifying patterns in text data by reducing the dimensionality of word-document matrices, and Principal Component Analysis (PCA), which reduces the number of variables in a dataset by identifying the most important features (principal components).

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is a widely used technique for dimensionality reduction in LLMs. PCA works by projecting high-dimensional data into a lower-dimensional space while retaining the maximum amount of variance in the data. Mathematically, PCA is performed by computing the eigenvectors of the covariance matrix of the data, where the eigenvectors corresponding to the largest eigenvalues represent the principal components. In the context of LLMs, PCA is often used to reduce the dimensionality of word embeddings or other high-dimensional representations to make models more efficient while retaining the core structure of the data. By focusing on the directions of greatest variance, PCA helps capture the most informative features of the input, which can significantly improve performance when training models on large datasets.

Figure 5: Illustration of PCA method for dimensionality reduction. useuse\\

Another application of eigen decomposition in LLMs is in spectral clustering, which is used to cluster data based on the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of a matrix that encodes similarities between data points. In LLMs, spectral clustering can be applied to group similar words, sentences, or documents, which improves the understanding of semantic relationships within a corpus. By leveraging the eigenvalues of a similarity matrix, spectral clustering captures complex relationships that traditional clustering algorithms like k-means may overlook.

One of the most impactful uses of SVD in LLMs is in Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA), a technique used to analyze relationships between a set of documents and the terms they contain. By applying SVD to a term-document matrix, LSA identifies patterns in the relationships between terms and documents, uncovering latent semantic structures. This allows for more effective information retrieval and topic modeling, as the dimensionality reduction helps in discovering deeper semantic meaning that might not be apparent at the surface level.

Eigenvalue problems are also critical in optimization and stability analysis in LLMs. Eigenvalues provide insights into how transformations affect the geometry of data, which is essential when analyzing the stability of optimization algorithms, such as gradient descent. In optimization, the Hessian matrix (the matrix of second-order partial derivatives) is used to evaluate the curvature of the loss function. The eigenvalues of the Hessian indicate whether the optimization is moving toward a local minimum (positive eigenvalues) or a saddle point (both positive and negative eigenvalues). Understanding the eigenvalue structure of the Hessian can help improve convergence and prevent instability during training, especially in non-convex optimization problems, which are common in LLMs.

From a practical standpoint, implementing these linear transformations and decomposition techniques in Rust can be highly efficient due to the language’s memory safety and performance guarantees. Libraries such as nalgebra provide robust tools for working with matrices, vectors, and linear algebra operations. For instance, the nalgebra crate offers built-in methods for performing SVD, PCA, and matrix decompositions. Below is an example of implementing PCA using Rust:

use nalgebra as na;

use na::{DMatrix};

// Function to perform PCA with Eigen decomposition

fn pca(matrix: &DMatrix<f64>, n_components: usize) -> DMatrix<f64> {

let n = matrix.nrows();

// Centering the matrix by subtracting the mean of each column

let mean = matrix.column_mean();

let centered_matrix = matrix - DMatrix::from_columns(&vec![mean; matrix.ncols()]);

// Covariance matrix (X^T * X / n)

let covariance_matrix = ¢ered_matrix.transpose() * ¢ered_matrix / (n as f64);

// Eigen decomposition of the covariance matrix

let eig = covariance_matrix.symmetric_eigen();

// Select top n_components eigenvectors (principal components)

let components = eig.eigenvectors.columns(0, n_components).into_owned();

// Project the data onto the principal components

centered_matrix * components

}

// Function to compute eigenvalues and eigenvectors for analysis

fn eigen_decomposition(matrix: &DMatrix<f64>) {

let eig = matrix.clone().symmetric_eigen(); // Cloning the matrix to avoid ownership issues

println!("Eigenvalues:\n{}", eig.eigenvalues);

println!("Eigenvectors:\n{}", eig.eigenvectors);

}

fn main() {

// Example data: 4 samples with 3 features

let data = DMatrix::from_row_slice(4, 3, &[4.0, 2.0, 1.0, // Sample 1

3.0, 1.0, 2.0, // Sample 2

1.0, 0.0, 1.0, // Sample 3

0.0, 1.0, 3.0]); // Sample 4

// Perform PCA for dimensionality reduction

let reduced_data = pca(&data, 2); // Reducing to 2 principal components

println!("Reduced data:\n{}", reduced_data);

// Perform Eigen decomposition for analysis

println!("\nEigen decomposition of covariance matrix:");

eigen_decomposition(&(&data.transpose() * &data)); // Pass reference to the result of matrix multiplication

}

This Rust code demonstrates the application of PCA using eigen decomposition to handle high-dimensional data in the context of LLMs. In LLMs, efficient handling of large matrices is crucial, and reducing the dimensionality of input features or embeddings can significantly improve model performance. The code begins by centering the data matrix (subtracting the mean) to ensure that the covariance matrix reflects the relationships between the variables. Next, it calculates the covariance matrix and performs eigen decomposition to extract the eigenvalues and eigenvectors. The eigenvectors corresponding to the largest eigenvalues are selected as the principal components, which capture the most variance in the data. The input data is then projected onto these principal components, effectively reducing its dimensionality while retaining the most informative features.

The eigen_decomposition function is also provided to analyze the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of any given matrix, which is important for understanding the behavior of linear transformations within LLMs. Eigenvalues give insight into how much each principal component contributes to the variance in the data, while eigenvectors represent the directions of these components. This process is fundamental in tasks like dimensionality reduction, spectral clustering, and latent semantic analysis (LSA), all of which are essential in optimizing the performance of LLMs by reducing the complexity of the input space without losing critical information. Rust's nalgebra library ensures that these computations are performed efficiently, handling large-scale data while maintaining numerical stability.

When applying eigen decomposition in LLMs, particularly in the attention mechanisms used in Transformers, eigenvalues and eigenvectors provide insights into how information is propagated and weighted across different layers of the model. The attention mechanism relies on matrix multiplication and linear transformations to compute attention scores between tokens in a sentence, and the eigen structure of these matrices can impact how effectively the model captures long-range dependencies between words. Optimizing these matrix operations using efficient eigen decomposition techniques ensures that attention mechanisms can scale to large datasets and longer input sequences without performance degradation.

One of the latest trends in matrix decomposition and its application in LLMs is the use of low-rank approximations to improve computational efficiency. By approximating large matrices with low-rank representations, models can reduce memory consumption and speed up matrix multiplications during training and inference. This is especially important in modern LLMs, where scaling up the number of parameters and the size of the training data is a common strategy to improve performance. Techniques like randomized SVD and sparse PCA are being explored to approximate matrix decompositions without sacrificing too much accuracy, making them ideal for large-scale LLM applications.

In conclusion, linear transformations and eigen decomposition are essential tools in the mathematical foundation of LLMs. Techniques such as SVD, PCA, and spectral clustering enable dimensionality reduction, efficient matrix computations, and semantic analysis, all of which improve model performance and scalability. Rust’s powerful libraries, like nalgebra, provide an efficient way to implement these techniques, allowing for large-scale matrix operations to be handled with precision and speed. By leveraging these methods, we can optimize LLMs to handle the ever-increasing demands of modern NLP tasks.

2.6. Discrete Mathematics

Discrete mathematics is a vital branch of mathematics that deals with distinct and separated values, as opposed to continuous mathematics, which involves smooth transitions and variations. In the context of Large Language Models (LLMs), discrete mathematics provides the tools and theoretical foundations for understanding structures like graphs, sets, and logical reasoning, all of which play essential roles in natural language processing. From efficient tokenization methods to decision-making processes in rule-based models, discrete mathematics is deeply integrated into the functioning and optimization of LLMs.

One key area of discrete mathematics relevant to LLMs is graph theory. A graph consists of nodes (or vertices) and edges, where the edges connect pairs of nodes. Graph theory provides a way to model relationships between entities, and one of its most significant applications in LLMs is in knowledge graphs. Knowledge graphs represent semantic relationships between concepts or entities, forming a network of interconnected data. In LLMs, knowledge graphs can be used to enhance models’ ability to answer questions, infer connections between concepts, and provide more accurate and contextually relevant outputs. For example, a knowledge graph in a medical LLM could help link diseases, symptoms, treatments, and medications, enabling more advanced medical question-answering systems. Graph algorithms such as graph traversal (breadth-first search, depth-first search) and shortest path algorithms (Dijkstra’s algorithm) are often used in extracting and querying knowledge from such graphs.

Another fundamental area of discrete mathematics is set theory, which deals with the concept of collections of objects, called sets. Boolean algebra extends set theory to logical reasoning, dealing with operations like AND, OR, and NOT, which form the basis for logical decision-making in many computational models. In the context of LLMs, Boolean logic is especially relevant in rule-based systems and decision trees, where models make decisions based on a set of logical rules. For example, a decision tree classifier can be used to classify text into different categories based on a series of Boolean logic operations on input features. These decision-making processes are integral to understanding how LLMs can be used in natural language understanding (NLU) and automated reasoning systems.

Combinatorics plays a crucial role in discrete mathematics, focusing on the counting, arrangement, and combination of elements within a set, and is particularly important in tasks like tokenization and sequence modeling in large language models (LLMs). Tokenization, the process of splitting text into smaller units such as words or subwords, frequently employs combinatorial techniques to handle large vocabularies efficiently. A prime example is Byte Pair Encoding (BPE), a subword tokenization method widely used in modern NLP models like BERT and GPT. BPE begins by breaking words into individual characters and iteratively merging the most frequent pairs of characters or subwords in a corpus to create new subword tokens, continuing this process until a predefined vocabulary size is reached. For instance, the word "machine" is initially split into \["m", "a", "c", "h", "i", "n", "e"\], and the most frequent pair, such as ("ch"), is merged into a new subword, resulting in \["m", "a", "ch", "i", "n", "e"\]. This combinatorial approach is formalized by selecting the pair of consecutive tokens $(x_i, x_{i+1})$ with the highest frequency, merging them into a single token, and updating the frequency table iteratively. BPE, as a greedy algorithm, captures common patterns in words while still accommodating rare or unseen words through reusable subword units. It optimizes tokenization by balancing vocabulary size and token granularity, thus improving the efficiency of managing vast corpora and reducing computational overhead. Additionally, in sequence modeling, combinatorics helps manage the enormous number of possible word sequences or combinations, especially in tasks like text generation or predicting the next token. Models like Transformers handle these combinatorial challenges using attention mechanisms, which allow the model to focus on the most relevant parts of the input sequence efficiently.

use std::collections::HashMap;

fn byte_pair_encoding(corpus: Vec<String>, vocab_size: usize) -> HashMap<String, usize> {

let mut token_freq: HashMap<Vec<String>, usize> = HashMap::new();

// Step 1: Tokenize words into individual characters

for word in corpus {

let chars: Vec<String> = word.chars().map(|c| c.to_string()).collect();

*token_freq.entry(chars).or_insert(0) += 1;

}

// Loop until we reach the target vocabulary size

while token_freq.len() < vocab_size {

let mut pair_freq: HashMap<(String, String), usize> = HashMap::new();

// Step 2: Count the frequency of adjacent pairs

for (tokens, freq) in &token_freq {

for pair in tokens.windows(2) {

let pair = (pair[0].clone(), pair[1].clone());

*pair_freq.entry(pair).or_insert(0) += freq;

}

}

// Step 3: Find the most frequent pair

if let Some((best_pair, _)) = pair_freq.into_iter().max_by_key(|&(_, count)| count) {

// Step 4: Merge the best pair

let mut new_token_freq: HashMap<Vec<String>, usize> = HashMap::new();

for (tokens, freq) in token_freq.into_iter() {

let mut merged_tokens = vec![];

let mut i = 0;

while i < tokens.len() {

if i < tokens.len() - 1 && (tokens[i].clone(), tokens[i + 1].clone()) == best_pair {

merged_tokens.push(format!("{}{}", tokens[i], tokens[i + 1]));

i += 2;

} else {

merged_tokens.push(tokens[i].clone());

i += 1;

}

}

*new_token_freq.entry(merged_tokens).or_insert(0) += freq;

}

token_freq = new_token_freq;

} else {

break; // No more pairs to merge

}

}

// Convert token frequencies into vocabulary

let mut vocab = HashMap::new();

for (tokens, _) in token_freq {

for token in tokens {

// Store vocab length before borrowing vocab mutably

let vocab_len = vocab.len();

vocab.entry(token).or_insert(vocab_len);

}

}

vocab

}

fn main() {

let corpus = vec!["machine".to_string(), "learning".to_string(), "machinelearning".to_string()];

let vocab_size = 10;

let vocab = byte_pair_encoding(corpus, vocab_size);

println!("BPE Vocabulary: {:?}", vocab);

}

This Rust implementation of Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) mimics the subword tokenization process used in models like BERT and GPT. It starts by splitting the input corpus into individual characters, treating each word as a sequence of characters. The algorithm then counts the frequency of adjacent character pairs and iteratively merges the most frequent pair into a new token. This process continues until the target vocabulary size is reached. The program outputs a vocabulary map where each subword (merged character pair) is assigned a unique token ID. This combinatorial technique efficiently reduces the size of the vocabulary while retaining common patterns in the corpus, making it suitable for processing large text datasets in LLMs.

Combinatorial optimization is also central to training LLMs. Many optimization problems in LLMs, such as finding the optimal model parameters or tuning hyperparameters, are combinatorial in nature. These problems involve searching through large, discrete sets of possibilities for the best solution. Techniques such as dynamic programming and greedy algorithms are often employed to find approximate solutions to these complex problems. For example, beam search is a combinatorial optimization algorithm used during inference in LLMs, where it efficiently searches for the most likely sequence of tokens by exploring a limited number of possible options at each step, rather than considering every possible combination.

Finite fields and modular arithmetic are critical in cryptographic applications, which have increasing relevance in LLM implementations where data privacy and security are essential. Cryptographic techniques ensure that sensitive data, such as medical records or financial transactions, are protected when processed by LLMs. Finite fields, which consist of a finite number of elements, are used in encryption algorithms, while modular arithmetic ensures that operations are confined to a fixed range of numbers, providing the backbone for many cryptographic protocols. As LLMs are integrated into more sensitive domains, ensuring that the models themselves, as well as the data they handle, are secure becomes crucial. Cryptographic approaches like homomorphic encryption, which allows computations to be performed on encrypted data without needing to decrypt it, are being explored to integrate security directly into LLM pipelines, enabling secure and private natural language processing.

The application of discrete mathematics in LLMs also extends to graph-based algorithms for analyzing linguistic structures and relationships. By representing words, phrases, or sentences as nodes in a graph and using edges to denote relationships (such as syntactic dependencies or semantic similarities), LLMs can better understand the structure of language. Graph-based algorithms like PageRank (originally used by Google for ranking web pages) can be adapted to rank the importance of words or concepts within a document or corpus, enhancing the model’s ability to understand context and relevance in text.

From a practical standpoint, implementing discrete mathematical techniques in Rust allows for efficient, high-performance solutions to problems involving graphs, sets, and combinatorial optimization. Rust’s powerful memory safety and concurrency features, combined with libraries such as petgraph for graph algorithms and ndarray for matrix and combinatorial operations, make it an excellent choice for handling the computational demands of large-scale LLMs.

The provided Rust code demonstrates how to create and visualize a directed graph using the petgraph and plotters crates. The graph represents relationships between various words or concepts, with nodes corresponding to words and edges indicating weighted connections between them. The code also utilizes Dijkstra's algorithm to find the shortest path between two nodes and visualizes the graph layout in a circular form, saving the final graph as an image file.

use petgraph::graph::{DiGraph};

use petgraph::algo::dijkstra;

use plotters::prelude::*;

use std::f64::consts::PI;

fn main() {

// Create a new directed graph using petgraph

let mut graph = DiGraph::<&str, u32>::new();

// Add nodes (vertices) representing words or concepts

let a = graph.add_node("word1");

let b = graph.add_node("word2");

let c = graph.add_node("word3");

let d = graph.add_node("word4");

let e = graph.add_node("word5");

// Add edges representing relationships between the words

graph.add_edge(a, b, 3); // word1 -> word2

graph.add_edge(b, c, 2); // word2 -> word3

graph.add_edge(a, c, 6); // word1 -> word3

graph.add_edge(c, d, 4); // word3 -> word4

graph.add_edge(d, e, 1); // word4 -> word5

// Use Dijkstra's algorithm to find the shortest path from node 'a' to 'e'

let result = dijkstra(&graph, a, Some(e), |e| *e.weight());

// Print the shortest path results

println!("Shortest path from 'word1' to 'word5': {:?}", result);

// Visualizing the graph using plotters crate

visualize_graph(&graph).expect("Failed to visualize the graph.");

}

// Function to visualize the graph using plotters

fn visualize_graph(_graph: &DiGraph<&str, u32>) -> Result<(), Box<dyn std::error::Error>> {

let root = BitMapBackend::new("simple_graph.png", (800, 800)).into_drawing_area();

root.fill(&WHITE)?;

let root = root.margin(20, 20, 20, 20);

let mut chart = ChartBuilder::on(&root)

.caption("Simple Graph Visualization", ("sans-serif", 40).into_font())

.build_cartesian_2d(-1.5..1.5, -1.5..1.5)?;

chart.configure_mesh().disable_mesh().draw()?;

let node_labels = ["word1", "word2", "word3", "word4", "word5"];

let node_count = node_labels.len();

// Create circular layout for nodes

let node_positions: Vec<(f64, f64)> = (0..node_count)

.map(|i| {

let angle = 2.0 * PI * (i as f64) / (node_count as f64);

(angle.cos(), angle.sin()) // Position in a circular layout

})

.collect();

// Draw nodes in circular layout with larger labels

for (i, &(x, y)) in node_positions.iter().enumerate() {

chart.draw_series(PointSeries::of_element(

[(x, y)],

10, // Larger nodes

&RED,

&|coord, size, style| {